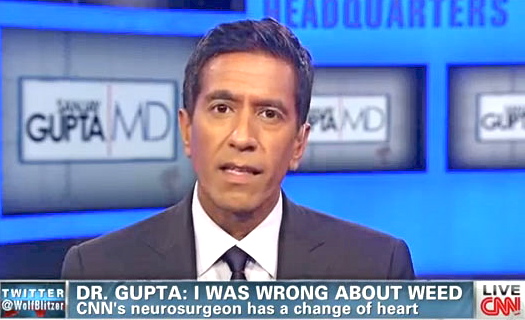

By Fred Gardner in O’Shaughnessy’s Spring 2005

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the case called Ashcroft et al v. Raich et al is likely to determine if and how the federal Controlled Substances Act applies to more than 100,000 people who use cannabis as medicine under the law in California and other western states.

The case was argued Nov. 29, 2004. The ruling is expected by June 2005.

A win for patient Angel Raich, her John Doe caregivers, and her co-defendant Diane Monson, would confer legitimacy on everyone in their situation. A loss could mean widespread, low-key terror with the DEA picking off growers, distributors and persons of interest at will.

There is a spectrum of possible outcomes in between the unambiguous win and loss (See “Robert Raich on the Judgment,” page 21.)

The suit started out as Raich et al v. Ashcroft et al. It was filed in October, 2002, in response to intermittent DEA raids, such as the raid that closed the 6th Street club in San Francisco, and the destruction of WAMM’s garden north of Santa Cruz.

Angel McClary Raich, 39, was the prime mover. Her life would be at risk, she contended, if the feds raided the two caregivers who were growing her year’s supply of cannabis (for no charge). Angel sought a court order enjoining the Justice Department and the Drug Enforcement Administration from carrying out any more raids.

Although painfully thin due to her afflictions, Angel (which is the name she chose for herself) has a strong ego and the will to make history —“for all of us,” she says.

She comes from Stockton, from a working-class family. Her parents divorced when she was four. Angel has disturbing memories of being molested by a family member. At 12 she was put in a full-body brace to correct curvature of the spine. She developed asthma and had several cysts removed while still in high school.

She married her high school sweetheart. They worked as apartment managers in the Central Valley and had two kids. They divorced. Angel remarried and worked at a series of blue- and white-collar jobs.

At age 30 she had a serious adverse reaction to the birth-control pill, resulting in partial paralysis. An inoperable brain tumor was diagnosed. Confined to a wheelchair, in pain, she was given strong prescription painkillers —synthetic opiates, methadone and Fentanyl— which induced nausea, vomiting and other intolerable effects.

She was hospitalized and made a feeble attempt to cut her wrists. A nurse advised her to try marijuana; Angel wouldn’t hear of it because it could cost her custody of her kids. When desperation ultimately led her to try the prohibited herb, her pain receded, and in due course she regained her mobility and found her calling as a martyr/advocate.

By 2000 Angel had moved from the Central Valley to the Bay Area, made friends with other patients and activists trying to implement California’s medical marijuana law, and formed a non-profit of her own called “Angel Wings Outreach.”

In the course of helping patients deal with legal problems, Angel met attorney Robert Raich. It was Raich who had the insight, back in 1998, that section 885(d) of the Controlled Substances Act, which allows undercover police officers to buy, handle, and sell narcotics, could apply to a city-authorized cannabis dispensary.

Raich represented the Oakland Cannabis Buyer’s Co-op in a federal case initiated by the Clinton Justice Department in 1998. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually ruled that the OCBC couldn’t claim “medical necessity” as grounds for violating the Controlled Substances Act. Whether an individual could claim “medical necessity” was not addressed in the OCBC case; it is one of the arguments Angel’s lawyers made on her behalf in the present case.

Angel’s co-defendants are two anonymous growers (“caregivers” in terms of California law) and Diane Monson, a 47-year old accountant who has her doctor’s approval to use cannabis to treat disabling back pain and spasms.

In August, 2002, Monson was growing six outdoor plants in her home garden in the foothills of Oroville. DEA agents arrived to question her about a large quantity of marijuana growing elsewhere in Butte County on property that she and her husband formerly owned and on which they still held the mortgage (i.e., they were getting monthly payments from the new owners).

Diane told the law enforcers she’d been unaware of the large grow. The DEA agents said they were going to confiscate her six plants then and there. (Ordinarily the feds don’t concern themselves with small quantities of marijuana.) Diane asked the Butte County Sheriff’s deputies who had accompanied the feds to confirm that the plants were legal under Prop 215.

A tense, three-hour standoff ensued during which the Butte County District Attorney, Mike Ramsey, asked the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of California, John Vincent, to call off the raid. Ramsey’s support is a tribute to his integrity (“He’s against medical marijuana, personally, but he respects and upholds California law,” says Philip A. Denney, MD, who has an office in Redding.) It’s also a tribute to the standing in the community of Monson and her recently deceased husband.

The DA of Butte County did not prevail, and as Diane Monson read aloud the text of Prop 215 (“I thought they needed to hear it,” she says), DEA agents macheteed and hauled away her almost-ready-to-harvest herbal painkiller.

Angel read about Monson’s plight and asked her to become a co-plaintiff so that a favorable decision by the Court could apply to patients whose illnesses were not life-threatening. The two women are represented by San Francisco defense specialist David Michael, and Randy Barnett, a professor of constitutional law at Boston University School of Law, an authority on the 9th amendment, in addition to Robert Raich.

Preliminary Injunction

In requesting an injunction they argued, among other things, that the federal government has no jurisdiction because the process by which the plants were grown for and consumed by Raich and Monson did not affect interstate commerce significantly.

The request for a preliminary injunction was denied in March 2003 by U.S. District Court Judge Martin Jenkins. Raich et al appealed to the 9th Circuit, and in October ’03, made their arguments to a three-judge panel (Pregerson, Paez and Beam, on loan from the 8th Circuit). In December ’03 the 9th Circuit panel (with Beam dissenting) directed the District Court Judge to issue the preliminary injunction. Jenkins did so in May 2004. It reads:

“Defendants, and their agents and officers, and any person acting in consort with them, are hereby enjoined from arresting or prosecuting Plaintiffs Angel McClary Raich and Diane Monson, seizing their medical cannabis, forfeiting their property, or seeking civil or administrative sanctions against them with respect to the intrastate, noncommercial cultivation, possession, use, and obtaining without charge of cannabis for personal medical purposes on the advice of a physician and in accordance with state law, and which is not used for distribution, sale or exchange.”

The above injunction —which the Bush Administration wants the Supreme Court to quash— is what made the summer of 2004 relatively stress-free for many Californians who were growing for or distributing cannabis to patients whose doctors had approved its use.

The Key Arguments

Before appearing in Court, each side makes its arguments in written briefs, which are supplemented by “amici” (friend of the court) briefs from interested parties.

The Justice Department brief, submitted by Acting Solicitor General Paul Clement, argues that Congress had a valid goal in passing the Controlled Substances Act to regulate interstate commerce in licit and illicit drugs. “Medical” users growing their own would undermine that goal. Interstate commerce, although not affected by a few instances of medical users growing their own cannabis in California, is inevitably affected when all such instances are considered in aggregate. All marijuana-related activity is inherently economic because marijuana is a “fungible” substance —it can be bought and sold in commerce. All marijuana is essentially the same, and if the parties in this case didn’t have marijuana grown for them, they’d be buying it on the market.

The government argues, “Excepting drug activity for personal use or free distribution from the sweep of the CSA would discourage the consumption of lawful controlled substances.”

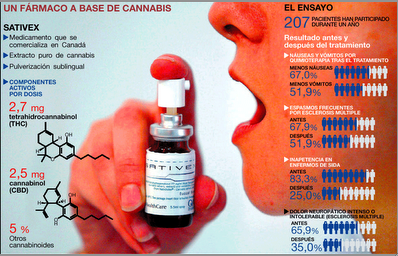

Among the feds’ arguments is one usually left unspoken: prohibition serves the interests of the pharmaceutical corporations. As expressed in the DOJ brief, “Excepting drug activity for personal use or free distribution from the sweep of the CSA would discourage the consumption of lawful controlled substances.” It would also undercut “the incentives for research and development into new legitimate drugs.” That’s as close as the government has come to acknowledging that wider cannabis use would jeopardize drug-company profits.

The U.S. Supreme Court overturns three out of four cases it chooses to review. The absence of Chief Justice Rehnquist (undergoing treatments for cancer) would work to Raich’s advantage. As a young lawyer in the Nixon Justice Department, Rehnquist helped write the Controlled Substances Act. His questions during the Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Co-op oral argument in 2001 were overtly hostile. And he’s considered results-oriented (fight the war on drugs) rather than principled (curtail the overreaching Commerce Clause). Rehnquist could still read the transcript and vote on the Raich case, even though he did not attend the oral argument. He is expected to write an opinion (or have his law clerks do so)… If there’s a 4-4 tie, the opinion of the 9th Circuit stands, but doesn’t become binding authority on the rest of the country.Most of the amici briefs focus on states’ rights. For those of us who remember the battles to end segregation in public schools in the South, there is obvious irony in our side calling for “states’ rights.” It was in the name of states’ rights that governors Orville Faubus and Ross Barnett barred the schoolhouse doors in Arkansas and Mississippi, while up north we were singing “The ink is black, the page is white, together we learn to read and write, to read and write. And now a child can understand this is the law of all the land —all the land!”

Another inversion involves the question of individual rights, to which so-called conservatives always pay lip service. The right to self-medicate is an individual right if ever there was one —but the conservatives are suddenly all about “public health,” like a bunch of bleeding-heart liberals!

The marijuana prohibition takes us through-the-looking glass because it’s based on the Mad Hatter’s premise that the drug is always harmful, never helpful. The feds and their amici refer to marijuana as only “purportedly,” “assertedly,” “allegedly” medical. But the record established at the district court level —which is supposedly all the Supreme Court goes on— consists of four declarations by the two patients and their physicians showing that cannabis does indeed have medical benefits. The government submitted no evidence to the contrary. They contend it’s just a question of law.

Precedent Case

The key precedent is a 1942 case, Wickard v. Filburn, which established that impact on interstate commerce is not a function of individual transactions (such as caregivers growing cannabis for Angel Raich) but of all such transactions, in aggregate (all medical users growing their own or having it grown for them within California).

Filburn was an Ohio farmer who grew more wheat than he was allowed to under the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which was intended to keep prices up by limiting production. That Act was clearly trying to regulate economic activity. The Court ruled that Congress could regulate consumption of Filburn’s wheat on his own farm because if all farmers acted likewise, Congress’s scheme to regulate the price would be undermined.

Raich-Monson argue that Wickard v. Filburn is a bad analogy because Filburn sold some of the wheat he raised, and much more of it was being consumed by his cows (from which he derived milk, and which he sold occasionally) than by his family. He also raised and sold chickens and he sold eggs, i.e., he was using his wheat in running a commercial farm. Moreover, the Agricultural Adjustment Act didn’t apply to farmers growing small quantities for family use. And the principle of “aggregation” established in Wickard did not apply in the two cases —Lopez (1995) and Morrison (2000)— by which the Rehnquist court has limited Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause.

Raich-Monson’s arguments are designed to appeal to “conservatives.” By ruling against them, the Court would significantly extend federal power under the Commerce Clause —the last thing “conservatives” supposedly want to do. “If the Court upholds Petiitioners’ claim of federal power,” the Raich-Monson brief points out, “this case will supplant Wickard to become the most expansive interpretation of the commerce clause since the Founding, and this Court’s landmark decisions in Lopez and Morrison will become dead letters.”