OLD FOOTAGE: I’m stepping out of my small office in the Hall of Justice slipping a cell phone into the breast pocket of my jacket. Kamala Harris sees me from about 60 feet away and walks swiftly down the hall, shaking her head in disapproval. “You shouldn’t do that,” she says. “My mother is a physician, a serious researcher, not given to faddish thinking. She says that data on the effect of microwave radiation on the heart isn’t strong enough to establish safety.” Since that warning from Dr. Harris’s daughter, not once in 20 years have I put my cellphone in the left breast pocket of my jacket. The woman knows how to drive home a point.*

I’m in Kamala’s office. enthusing about the city of Alameda, where we might be able to afford a house: “Marci loves that it’s 10 degrees warmer than San Francisco. Not only is housing cheaper, it’s friendlier, it’s better integrated, you don’t have to make your way around strung-out people on the sidewalks, there’s a long sandy beach to walk on…” Kamala nodded as I listed the glories of the Island City. “I’m glad to hear that it’s changed,” she said, as if she didn’t wholly believe my rap. “When I was a teenager we couldn’t go to parties there. The Alameda police would stop us when we came through the tunnel.”

CUT TO THE PRESENT: Willie Brown writes in the Chronicle August 16, “The Biden camp is staffing Harris’ campaign operation with its people, rather than letting her bring in her own team. Essentially, the plan is to envelop Harris in a Biden blanket.” Her assignment while wrapped in DNC polyester is to inspire “progressive” rank-and-file Democrats to support and work for Joe Biden. To pull off this political Houdini Act, it’s crucial that Kamala be seen as “progressive” herself.

To burnish Kamala’s “for-the-people” credentials MSDNC’s Rachel Maddow had longtime San Francisco Public Defender Niki Solis on her show. According to Solis, “Harris was the most progressive prosecutor in the state. This is not an anecdotal opinion. It is based on facts. As San Francisco DA, Harris refused to seek the death penalty —even on a case where a very respected police officer was tragically killed. Marijuana sales cases were routinely reduced to misdemeanors. And marijuana possession cases were not even on the court’s docket. They were simply not charged. Unless there was a large grow case, or a unique circumstance, this was the reform-minded approach then-DA Harris’ office took. The accusations about marijuana prosecutions being harsh during her tenure are absurd. The reality was quite the opposite.

Niki Solis makes much of Kamala Harris’s leniency in prosecuting marijuana sales cases. She doesn’t note that the political risk for Harris had been greatly reduced by the passage of San Francisco’s Proposition P, introduced by Hallinan as a supervisor in 1991, and California’s Proposition 215 in 1996, which Hallinan had been the only DA in the state to support. Would Kamala have stood alone like that? After Prop 215 passed, as recounted earlier in this memoir, Hallinan urged his fellow district attorneys to leave implementation up to their county health departments. (San Francisco is a unique jurisdiction —both a city and a county.) Kamala quietly welcomed the new political reality created by Prop 215, but it was Kayo who helped make it come to pass.

During his eight years as district attorney, Hallinan maintained strong ties to the medical marijuana community —dispensary owners, growers, and consumers. To cite but one example here, arly in 2001 the Medical Board of California subpoenaed the records of 46 patients whom Tod Mikuriya, MD, had authorized to use cannabis in treating various conditions. Mikuriya filed a civil suit to protect his patients’ privacy. Hallinan weighed in with a statement of support:

“It is no coincidence that the Medical Board is going after Tod Mikuriya. Most California doctors have taken the federal threats very seriously and are afraid to risk their licenses. Hundreds of others have bravely written recommendations for patients with AIDS and cancer, but when it comes to conditions like arthritis and pain and depression and insomnia, only the bravest of the brave are willing to risk the wrath of government inquisitors. That is why Tod Mikuriya has become the doctor of last resort for thousands of patients in California. And that is why he has been the subject of so many complaints to the medical board —not from patients, but from law enforcement officials who refuse to accept that marijuana really does have a wide range of medical uses.

“It’s time for the state medical board to accept reality. It’s time to heed the message that the voters of California sent when they passed Prop 215. Tod Mikuriya is deserving of honor and his patients are deserving of privacy.”

No individual is indispensable in a social movement whose time has come. And yet Dennis Peron was the indispensable organizer of the medical marijuana movement, Tod Mikuriya, MD, the indispensable physician, and Terence Hallinan the indispensable politician. Without those three brave characters, legalization for medical use would not have happened in California in 1996.

PS October 27, 2024

Today’s New York Times features a big story by Robert Draper about Kamala’s career. It doesn’t note that her rise from SFDA to Attorney General of California in 2012 was made possible by money and campaign workers from the medical marijuana movement (which was then burgeoning into The Industry). Her opponent, Los Angeles DA Steve Cooley, was feared and despised by dispensary operators. Kamala had not yet come out as a pot partisan, but she certainly wasn’t a prohibitionist.

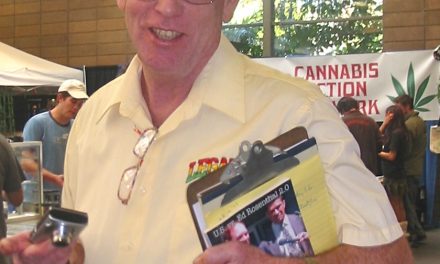

Terence Hallinan with Mary Rathburn (“Kayo” and “Brownie Mary”) at a pro-cannabis rally. In background at right is John Hudson of the “Flower Power” dispensary.