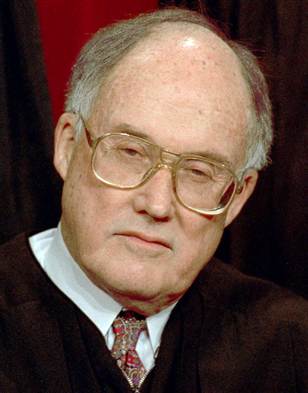

Judge William Rehnquist, appointed to the US Supreme Court by Richard Nixon in 1971 and elevated to Chief Justice by Ronald Reagan in 1986, died in 2005. (George W. Bush named John Roberts to succeed him.) Rehnquist’s obituaries ignored his longterm addiction to a pharmaceutical downer, Jack Shafer of Slate observed in a piece excerpted below:

William Rehnquist ordered that the Chief Justice’s robe her adorned with four gold stripes after being impressed by a costume in a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta.

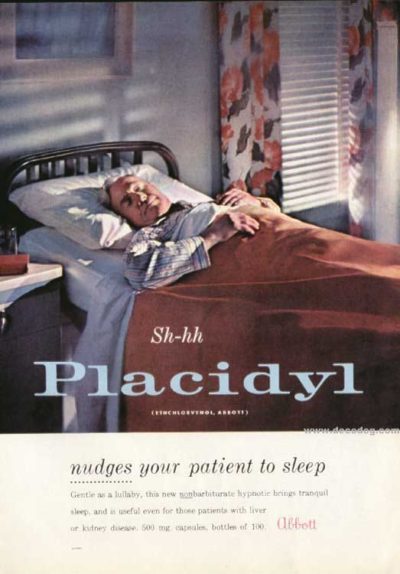

… For the nine years between 1972 and the end of 1981, William Rehnquist consumed great quantities of the potent sedative-hypnotic Placidyl. So great was Rehnquist’s Placidyl habit, dependency, or addiction —depending on how you regard long-term drug use—that by the last quarter of 1981 he began slurring his speech in public, became tongue-tied while pronouncing long words, and sometimes had trouble finishing his thoughts…

The 1986 medical report on Rehnquist described him as seriously “dependent” on Placidyl from 1977 to 1981. He often consumed three month’s worth of the drug in one month before requesting more from Dr. Freeman H. Cary, the attending physician to Congress, who prescribed it. Anonymous sources told the Post that Cary first prescribed Placidyl to Rehnquist in 1971 to help him sleep through his severe back pains, but “Cary reportedly told the FBI that Rehnquist had taken it before.”

… The abuse potential of Placidyl has always been rated as high: An associate professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University told the Post in 1986 that it was “a strong drug I would use only under very exceptional circumstance” and that he wouldn’t give it to people for more than one or two weeks. He added that it shouldn’t be given to patients who suffered both pain and insomnia.

The standard dose for adults is 500 milligrams, taken at bedtime. Rehnquist initially took 200 milligrams daily but by 1981 was taking 1,500 milligrams a day. Increasing dosage indicates drug dependency, the Johns Hopkins professor explained. For more about Placidyl’s potency, see this “product information”from 1971 distributed by the Abbott Laboratories, the manufacturer in the early 1970s, and reprinted in Licit and Illicit Drugs by Edward M. Brecher…

According to a Jan. 4, 1982, New York Times account, Rehnquist sought help with the drug in December 1981 because it no longer relieved his pain. He entered George Washington University Hospital on Dec. 27. According to the physician spokesman for the hospital he suffered “disturbances in mental clarity, characterized by distorted perceptions,” as doctors weaned him off the drug. The spokesman added that after his Placidyl was cut off, Rehnquist began ”hearing things and seeing things that other people did not hear and see.” The doctors took his dose back up before re-weaning him. By mid-January, Rehnquist returned to the bench.

When Rehnquist’s drug problem became an issue during the 1986 confirmation hearings, Sen. Orrin G. Hatch, R-Utah, defended Rehnquist in a Post story, saying he got into trouble with Placidyl because he was “a very compliant patient” who “followed the advice” of his doctors. Ah, yes, one of the most brilliant jurists of his time was the victim of his rotten doctors for almost a decade! Are we to believe that one of the court’s sharpest minds never availed himself of a Physicians’ Desk Reference for independent medical information, or in any way tried to educate himself about the drug he was taking in larger and larger quantities? The Senate Judiciary Committee asked Rehnquist no questions about his drug use, and he was, of course, confirmed as chief justice. The debate over whether Rehnquist’s drug use might be relevant to his fitness to serve as chief never got started.

Wikipedia on Placidyl

Ethchlorvynol is a GABA-ergic sedative and hypnotic/soporific medication developed by Pfizer in the 1950s. In the United States it was sold by Abbott Laboratories under the tradename Placidyl.

Ethchlorvynol is a GABA-ergic sedative and hypnotic/soporific medication developed by Pfizer in the 1950s. In the United States it was sold by Abbott Laboratories under the tradename Placidyl.

Along with expected sedative effects of relaxation and drowsiness, adverse reactions to ethchlorvynol include skin rash, faintness, restlessness and euphoria. Early adjustment side effects may include nausea and vomiting, numbness, blurred vision, stomach pains and temporary dizziness. There are no specific antidotes available for ethchlorvynol, and treatment is supportive with protocols resembling those for the treatment of barbiturate overdose. Overdose may be marked by a variety of symptoms, including confusion, fever, peripheral numbness and weakness, reduced coordination and muscle control, slurred speech, reduced heartbeat, respiratory depression, and in extreme overdoses, coma and death.

As with all GABAA receptor agonists, Placidyl can be habit forming and extremely physically addictive (with potentially lethal withdrawal resembling delirium tremens and benzodiazepine withdrawal). After prolonged use, withdrawal symptoms may include convulsions, hallucinations, and amnesia. As with most hypnotics, Placidyl was indicated for use in the treatment of insomnia for a short period of time (a week or two). However, it was nonetheless not uncommon for doctors to prescribe Placidyl (and other hypnotics) for extended periods of time, as currently prescribed soporifics are today.

During the late 1970s, ethchlorvynol was sometimes over-prescribed causing a minor epidemic of persons who quickly became addicted to this powerful drug. Occasional deaths would occur when addicted persons would try to inject the drug directly into a vein or artery.

Retro Message: Liberal Censorship

This is how censorship works in Our Brilliant System. It’s not that stories of great significance don’t get reported; it’s that they don’t get publicized enough to reach the masses. Merck executives killed between 27,000 and 51,000 Americans with Vioxx — more than 10 times as many than Osama’s operatives killed on 911 with airplanes. But the Vioxx story vanished soon after FDA maverick David Graham, MD, documented Merck’s deadly deceit in testimony to Congress.

Those of us following the medical marijuana movement saw a perfect example of liberal censorship when Donald Tashkin, MD and colleagues at UCLA established that smoking the herb does not cause lung cancer. O’Shaughnessy’s reported Tashkin et al’s findings to some 20,000 readers, and a peer-reviewed journal published their study. But the corporate media —dependent on Big PhRMA advertising— chose not to convey the news.

Why was the story of William Rehnquist’s drug addiction and its acceptance by his peers suppressed? Because it revealed all too clearly that the so-called “War on Drugs” is really a war on certain people who use certain drugs. —Fred Gardner