“Learning to Love GMOs” was the title of the NY Times Sunday Magazine’s cover story July 25 —an enthusiastic endorsement of genetically modified foods. It had aura of a PR campaign, the kind that accompanied the marketing of Prozac some 30 years ago.

For readers who might not wade through the 7,000-word puff piece by Jennifer Kahn, the gist was provided in bold print on the magazine cover, alongside a cross-section of a tomato with dark purple flesh: “Overblown fears have turned the public against genetically modified food. But the potential benefits have never been greater.”

The article was preceded in the print edition by a two-page spread restating the title in 2-inch high capital letters — “LEARNING TO LOVE G.M.O.S”— framing a big color photo of a papaya in cross-section. Turn the page and there’s a big color photo of two sugar beets, each with a caption. One says, “Produces more pounds of sugar per acre.” The other says, “Holds up to glyphosate, a common pesticide.” Glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup, is sold as an herbicide, not a pesticide. Maybe some Times editor remembered reading that Roundup had decimated the Monarch butterfly population. It had, but that was a consequence of Roundup decimating the milkweed that sustained the lovely orange insects.

“Holds up to glyphosate” really means “drenched with Roundup.” Glyphosate has been identified as a carcinogen, is already banned in Austria, and will be banned in the EU by the end of next year. Personal injury lawyers are trolling for US workers who developed cancers after heavy exposure to Monsanto’s deadly potion.

A character in her own story, Kahn writes that she has flown to Norwich, England to interview Cathie Martin, a plant biologist. Martin “has spent almost two decades studying tomatoes, and I had traveled to see her because of a particular one she created: a lustrous, dark purple variety that is unusually high in antioxidants, with twice the amount found in blueberries.”

You wouldn’t know it from the Times piece, but it doesn’t take gene-splicing technology to develop an antioxidant-rich purple tomato. A delicious one called “Indigo Rose” was developed by an Oregon State Professor of Vegetable Breeding and Genetics, Jim Myers, by conventional breeding methods. Its listing in the Spring 2015 catalog from a Vermont seed company, Johnny’s, was noted in the real paper of record (the one you’re reading), which advised gardeners: “Consider ‘Indigo Rose,’ which Johnny’s catalog describes as ‘the darkest tomato bred so far, exceptionally high in anthocyanins.’ Anthocyanins are flavonoids that contribute purple pigment to eggplants (and cannabis), red to grapes, blue to blueberries. They are potent antioxidants… Hemp isn’t the only useful plant that we’re missing out on, being so disconnected from nature in this dying culture… Some hip dispensary ought to buy a thousand seeds (price: $10.15) and give out packets to their grower-members as a wee first step out of the single-issue trap.” None did, of course.

Getting back to the now and Jennifer Kahn’s glorification of Cathie Martin: “The purple tomato is the first she designed to have more anthocyanin, a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory compound. ‘All higher plants have a mechanism for making anthocyanins,’ Martin explained when we met. ‘A tomato plant makes them as well, in the leaves. We just put in a switch that turns on anthocyanin production in the fruit.’ Martin noted that while there are other tomato varieties that look purple, they have anthocyanins only in the skin, so the health benefits are slight.

“The difference is significant. When cancer-prone mice were given Martin’s purple tomatoes as part of their diet, they lived 30 percent longer than mice fed the same quantity of ordinary tomatoes; they were also less susceptible to inflammatory bowel disease.”

In context, “ordinary tomatoes” seems to mean “other tomato varieties that look purple,” like Myers’s Indigo Rose. But it just as well could mean a Shady Lady or Early Girl that Cathie Martin grew to use as her control. This is not a minor ambiguity; an editor should have caught it and asked for clarification.

After Martin published her findings in Nature Biotechnology in 2008, the media showed great interest. “She considered making the tomato available in stores or offering it online as a juice,” Kahn reports, “But because the plant contained a pair of genes from a snapdragon — that’s what spurs the tomatoes to produce more anthocyanin — it would be classified as a genetically modified organism: a G.M.O.”

Enter the villain of the story, government regulation. “Martin had envisioned making the juice on a small scale, but just to go through the F.D.A. approval process would cost a million dollars. Adding U.S.D.A. approval could push that amount even higher… ‘I thought, This is ridiculous,’ Martin told me.”

Martin has persisted, however, and she disses those expressing concern as “WWWs… the well, wealthy, and worried.” She distinguishes her little company from the DowDuPonts, and Kahn is very sympathetic: “Martin’s tomato wasn’t designed for profit and would be grown in small batches rather than on millions of acres: essentially the opposite of industrial agriculture. The additional genes it contains (from the snapdragon, itself a relative of the tomato plant) act only to boost production of anthocyanin, a nutrient that tomatoes already make.

“Nonetheless, the future of the purple tomato is far from certain. ‘There’s just so much baggage around anything genetically modified,’ Martin said. ‘I’m not trying to make money. I’m worried about people’s health! But in people’s minds it’s all Dr. Frankenstein and trying to rule the world.'”

Kahn provides some interesting info: “Roughly 94 percent of soybeans grown in the United States are genetically modified, as is more than 90 percent of all corn, canola and sugar beets, together covering roughly 170 million acres of cropland… There are now more than 55,000 products carrying the ‘Non-G.M.O. Project Verified’ label on their packaging. Nearly half of all U.S. shoppers say that they try not to buy G.M.O. foods… Consumers will pay up to 20 percent more to avoid them.”

Monsanto required farmers to sign contracts vowing not to save seeds for replanting. “At one point, the company had a 75-person team dedicated solely to investigating farmers suspected of saving seed — a traditional practice in which seeds from one year’s crop are saved for planting the following year — and prosecuting them on charges of intellectual-property infringement.”

To Kahn, “Golden Rice” is a “beneficial product.” It was developed in 1999 “by university researchers hoping to combat vitamin A deficiency, a simple but devastating ailment that causes blindness in millions of people in Africa and Asia annually, and that can also be fatal. But the project foundered after protests by anti-G.M.O. activists in the United States and Europe, which in turn alarmed governments and populations in developing countries.”

I thought the project foundered because Golden Rice was providing Vitamin A to starving people who could hardly digest it, their diets being almost devoid of fat. The rice had to be stored at very low temps and there were other factors that made its widespread use impractical in the Third World.

Kahn of the Times was given a tour of Martin’s “surprisingly modest” greenhouse. She met Eugenio Butelli, who was “trying to modify a tomato to produce serotonin, a neurotransmitter used in antidepressant drugs. When I asked whether antidepressant tomatoes were next, Martin shrugged. ‘He’s playing,’ she said. ‘A lot of what we do is play.’

“Farther down the row was the next-generation purple tomato: a dark blue-black variety called Indigo (sic) that Martin has created by crossing the high-anthocyanin purple tomato with a yellow one high in flavonols, an anti-inflammatory compound found in things like kale and green tea, making it even richer in antioxidants. The Indigo, which is also a G.M.O., is too new to have been evaluated for health benefits, but Martin is hopeful that it will have even more robust health effects than the purple tomato…

“There are some signs that the future of small-scale, bespoke G.M.O. produce may already have begun. In late April, Cathie Martin told me that the U.S.D.A. had recently updated its regulations to allow more G.M.O. plants to be grown outside, without a three-year field trial or in tightly contained greenhouses. (The exceptions are plants or organisms with the potential to be a pest, pathogen or weed.) In the wake of this change, Martin and Jones are planning to make the purple tomato available first to home gardeners, who could grow it from seed as soon as next spring — well before the commercially grown tomato reaches grocery stores. (U.S.D.A. approval is expected by December.)”

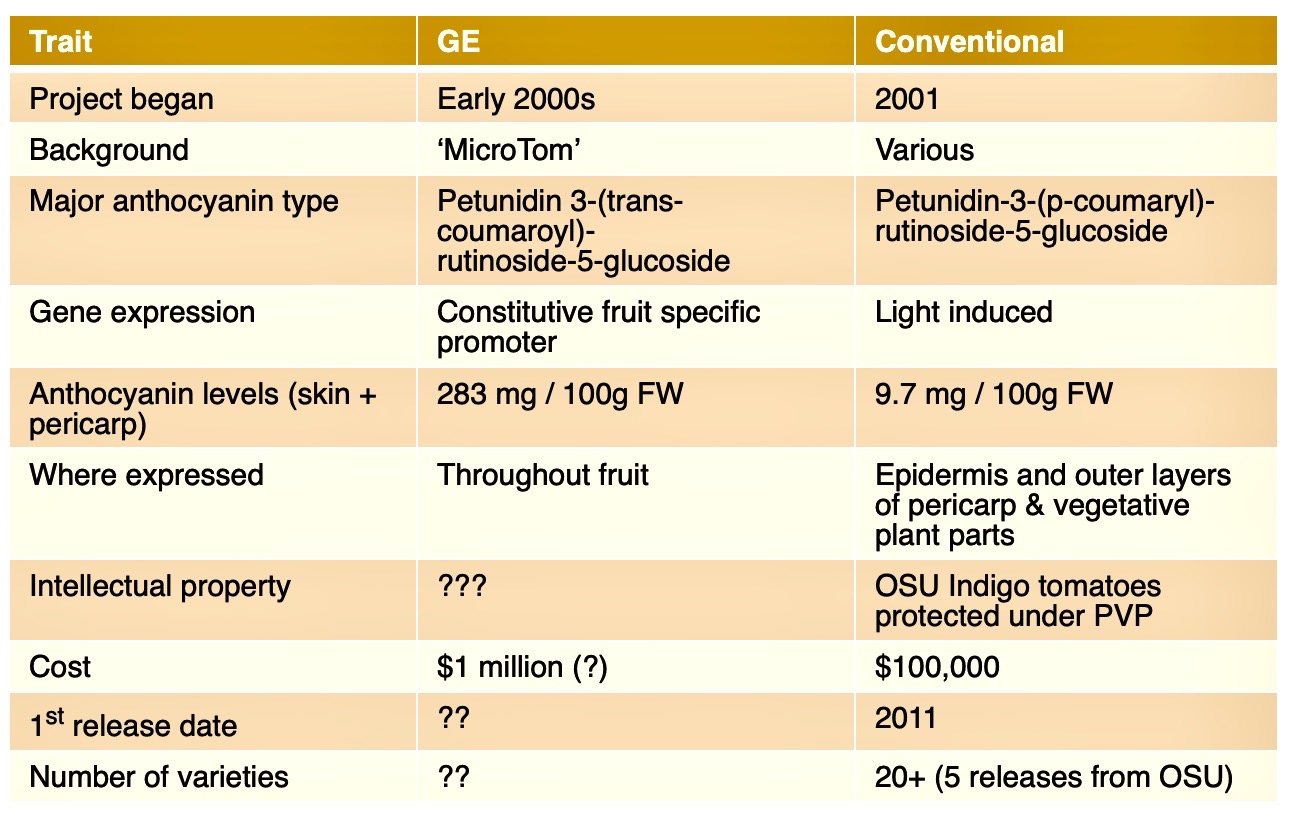

Meanwhile, back in Corvallis, Jim Myers has released Indigo Cherry Drops, Indigo Pear Drops, Indigo Kiwi, and Midnight Roma, all developed by traditional breeding methods, and has shared his germ plasm with other plant breeders. Asked to comment on the Times piece, he sent a diplomatic email contrasting Martin’s progress and his own. (Go, Beavers!)

The NY Times article provides a good snapshot into what is currently going on with the GMO program. The work started about 20 years ago and there remains nothing commercial on the market. In 2014 when the program was last in the international news, Dr. Martin was quoted as saying regulatory approval would be in a couple years and we would see a release then, which did not happen, and I see that presently they are looking at approval by the end of this year. In the same period of time, we’ve released five Indigo tomatoes from the OSU program and other breeders have released so many more that I have lost track of how many Indigo varieties there are now.

I noticed several years ago that Dr. Martin was using the ‘Indigo’ word to describe their tomatoes and it looks like this may be the name of their first release. When we were developing our high anthocyanin tomatoes, we wanted to differentiate them from the heirloom ‘blue’ and ‘black’ tomatoes, which do not possess anthocyanins, which is why we chose the term ‘Indigo.’ In the present case, I am afraid that the use of the name by Dr. Martin’s program will sow confusion as to what is GMO and what is not. I am already receiving inquiries as to whether the OSU tomatoes are GMO.

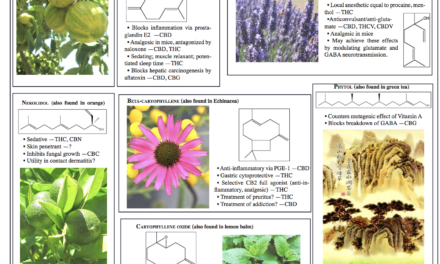

From a scientific standpoint the GMO tomato work has been very interesting for studies into gene expression as well as investigating the health benefits of anthocyanins from a tomato source. Below you will find a table comparing the GMO and conventional tomatoes.

PVP refers to the USDA’s Plant Variety Protection Office which, according to its website,

provides intellectual property protection to breeders of new varieties of sexually reproduced, tuber propagated, and asexually reproduced plant varieties. Implementing the Plant Variety Protection Act (PVPA), we examine new applications and grant certificates that protect varieties for 20 years (25 years for vines and trees). Our certificates are recognized worldwide and allow faster filing of PVP in other countries. Certificate owners have rights to exclude others from marketing and selling their varieties, manage the use of their varieties by other breeders, and enjoy legal protection of their work.

In the U.S. there are 3 types of intellectual property protection that breeders can obtain for new plant varieties:

- Plant Variety Protection – seeds, tubers, and asexually reproduced plants (issued by PVPO)

- Plant Patents – asexually reproduced plants (issued by the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO)

- Utility Patents – for genes, traits, methods, plant parts, or varieties (issued by the PTO)