By Jeff Meyers with Tom Banks for O’Shaughnessy’s Winter/Spring 2017 The Sixties cultural revolution brought protests and social upheaval to college campuses, embroiling the student body, but not the big men on campus. Conditioned to obey authority and unite together as a team, football players generally followed their coach’s orders and stayed on the sidelines during anti-war protests.

Yet these same players were secretly engaging in an activity that was far riskier than a sit-in at the dean’s office. Making common ground with hippies, peaceniks and feminists, a goodly number of players on every college team in America defied their coach and smoked marijuana, an act that could have gone beyond suspension to expulsion, jail, or, in some states, life imprisonment.

These weed-loving athletes ranged from benchwarmers to All-Americans, many of them going on to stardom in the National Football League. Theirs was the first generation of pro players to embrace marijuana. Because the NFL did not test for pot use, future Hall of Famers, All-Pros and rookies alike felt free to toke up during the season with the best bud in town, courtesy of well-connected fans.

The situation changed in 1982. That’s when the NFL began year-round random drug testing for marijuana and handed out harsh week-long or even season-long suspensions for testing positive. The new policy —to which the National Football League Players Association consented— deterred pot-smoking, especially during the season.

A research opportunity? We look back at the league’s Golden Age of Ganja and see a possible research opportunity for neurologists. Having consumed marijuana during every football season, the stoners who played before drug testing are a unique cohort. They could be living proof that pot protected them from the game’s brain-rattling blows.

As a young sports writer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, I was the beat writer for the then-St. Louis Cardinals from 1970-74. In an era when nearly 90 percent of Americans were anti-pot, half the team smoked. How do I know this? I smoked out with many of them. I was turned on for the first time in 1971 by one of the team’s star players. And because I was now a bonafide pothead, my off-campus apartment at training camp became a cloud-filled, post-scrimmage refuge for the stoners.

Earlier this year, after watching the movie “Concussion” —a heartbreaking, true story about the devastating effects of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)— I decided to check in with a few of the old Cardinals to see how they were doing.

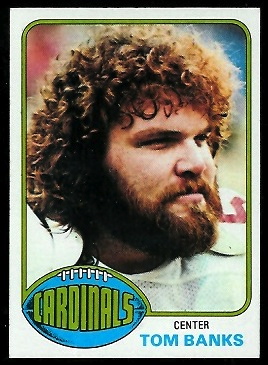

The first player I contacted was Tom Banks, a gregarious Alabaman with a hearty laugh and way too many knee and hip replacements. An All-Pro center on a great offensive line, Banks smoked marijuana most every day during his 10 seasons, even before games. Although pot was supposed to make him lazy and unmotivated, Banks managed to play in four Pro Bowls.

We kept in touch over the years. Banks hadn’t seen “Concussion” but knew a lot about CTE . While his body may be damaged, his mind is as sharp as ever despite the big hits he absorbed in every one of his 116 NFL games. Banks figures he sustained five to 10 such collisions each game, amounting to many hundreds during his career.

Current research into CTE is focusing not only on concussions but also looking into the effects of constant head-against-head contact —something experienced mostly by offensive and defensive linemen.  In “Concussion,” Dr. Bennet Omalu, who discovered CTE, considered the center position as the most violent in terms of constant head-banging. He calculated that CTE victim Mike Webster, featured in the film, endured approximately 70,000 blows to the head playing center for 17 years, primarily with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

In “Concussion,” Dr. Bennet Omalu, who discovered CTE, considered the center position as the most violent in terms of constant head-banging. He calculated that CTE victim Mike Webster, featured in the film, endured approximately 70,000 blows to the head playing center for 17 years, primarily with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Webster died at 50 in 2002 after suffering for years from symptoms of dementia, amnesia and depression. His brain tissue was examined and CTE was confirmed, making Webster the first NFL player diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disease. Omalu concluded that “playing football killed Mike Webster.”

I asked Banks if his pot-smoking teammates –most of whom are now in their late 60s and 70s— were having any serious neurological problems. He said he wasn’t sure but didn’t think so. We decided to find out.

With input from O’Shaughnessy’s Managing Editor Fred Gardner, we designed a 29-question survey for former pot-smoking Cardinals. Banks made phone calls to former teammates while recovering from a surgical tune-up on his hip replacement.

The survey was mailed early in September to 30 confirmed stoners who played for the Cardinals (and other teams) in the years before drug testing.The survey was anonymous, but several players allowed their names to be used. Of those 30 stoners, 23 responded, either by mailing in the survey or providing information over the phone.

We were all shocked to learn that a West Coast teammate, a linebacker for eight seasons, died two years ago at age 70. Post-mortem tests revealed CTE, a family member told us.

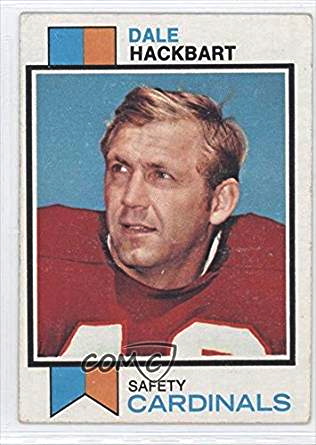

Three players are experiencing memory problems associated with aging, such as  forgetfulness. A fourth player is having symptoms of neurodegenerative disease. And a fifth, 78-year-old ex-defensive back Dale Hackbart, has been diagnosed with early stage dementia. While many of the other players are physically challenged because of football-related structural injuries, they all report to be in good shape cognitively, despite all their head trauma and the egregious medical treatment they received.

forgetfulness. A fourth player is having symptoms of neurodegenerative disease. And a fifth, 78-year-old ex-defensive back Dale Hackbart, has been diagnosed with early stage dementia. While many of the other players are physically challenged because of football-related structural injuries, they all report to be in good shape cognitively, despite all their head trauma and the egregious medical treatment they received.

All survey responders — only one of whom retired from football because of concussions— agreed that the NFL and its doctors did not take concussions seriously back then. But neither did they themselves. “It was a badge of honor” to ignore a head injury and stay in the game, Hackbart said. “You can’t let your teammates down.”

When players refer to being in “football shape,” it meant being able to “live with the pain and shake it off,” an ex-running back said. These unrelenting aches and pains gave players a gallows sense of humor. At practice, it was customary to laugh at a teammate whose bell had been rung. Or dinged, another euphemism making light of brain trauma.

How does it feel to get concussed? “It was an unbelievable feeling,” said a 10-year veteran. “The body was extremely weak, with little to no control over muscles or limbs. I felt totally disoriented. You would want to get off the field but were unable to make decisions… or know where you were. There was a ringing sensation in my ears and my head. I would have headaches that lasted for a long time afterwards. My tongue even felt a thickness to it.”

No one knows more about big hits than Hackbart. In 14 years as a pro, the 210-pound defensive back was known to deliver vicious blows —and receive them. While Banks was lucky to have sustained only two concussions during his career, Hackbart seriously believes he’s had hundreds and taken thousands of violent hits.

Hackbart was knocked unconscious twice. He was kneed in the temple. He was so disoriented after a big hit, he wobbled to the sideline and sat down on the opposing team’s bench. He survived head-to-head collisions, barely survived an elbow to the back of the neck that fractured C-4-5-6-7 vertebrae. The injury ultimately required surgery and ended his career, but true to the NFL’s macho culture and clueless doctors,

Hackbart played the second half of that game after a team doctor diagnosed his injury as “a stinger.” No X-rays were taken.

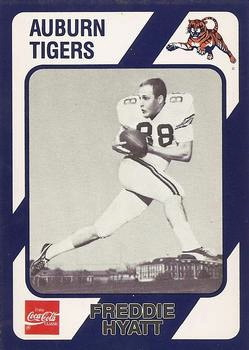

Freddie Hyatt, a 6-3 wide receiver, was diagnosed with five concussions during the  course of his football career. He was once knocked out on the first play of an NFL game and woke up with 20 seconds left in the fourth quarter. He was not tested by the team doctors. After the players’ day off, he reported to practice. And played the following Sunday.

course of his football career. He was once knocked out on the first play of an NFL game and woke up with 20 seconds left in the fourth quarter. He was not tested by the team doctors. After the players’ day off, he reported to practice. And played the following Sunday.

Until the symptoms resolve after a concussion —which can take days or weeks— the brain is extremely susceptible to re-injury. But players only came out of games after a big hit if they were seeing stars or had to be carted off. Two-thirds of the survey participants said they were sent back in after being concussed. “I went back in with a concussion three or four times and never missed a game,” said offensive lineman Joe Bostic, who played in the NFL for 11 seasons and is the youngest responder at 59.

In answering the question of how many times he returned to the field with concussion-like symptoms, Cardinals All-Pro guard Conrad Dobler wrote “every time.” How many concussions does he think he had during his 10-year career? “I’m not sure … they didn’t even call it [a concussion] then.”

The ex-running back, who believes he suffered five concussions in his seven-year NFL career agreed with Dobler. “I don’t think anyone ever used the word ‘concussion,’” he said.

How did the doctors treat players in the moments after head trauma? “They wagged their forefinger in front of your face, asked you what your name was, popped an ammonia capsule under your nose and sent you back in the game,” said an offensive lineman with eight concussions in his overall football career.

There were no neurologists on the sideline at Cardinals’ games. The team doctors were orthopedic surgeons, general practitioners and MDs.

“We were assets to them,” one player noted in his survey responses. “If they treated us like real patients, they would have been more diligent” about concussions.

Freddie Hyatt: “The doctors were not that aware of the situation back then, and the players were not conscious of the doctors’ approach being bad down the road.”

AstroTurf Adds to the Damage It wasn’t only the big hits causing concussions. The Cardinals were pioneers in the new world of plastic grass. AstroTurf, which was manufactured in St. Louis by Monsanto, was installed at Busch Stadium in 1970 for the baseball Cardinals, without considering the ramifications for the football players who would practice on it every day.

An AstroTurf carpet on top of a thin pad sitting on an asphalt base was satisfactory for baseball players, but devastating for the football players whose profession revolves around getting knocked to the ground. AstroTurf caused head, neck and other injuries.

“It was easier to see stars when your head hit the turf,” is how Conrad Dobler put it.

An ex-quarterback has a more detailed description: “The impact of the head on that surface with no cushion forces the skull to absorb the entire impact… and the brain rattles in the skull.”

The hard surface made the players faster than on real grass and led to “more big collisions during practice,” Banks observed. Those big collisions could launch a player, the hard landing “bouncing him off the turf, which equals another collision.”

Hackbart said: “It’s definitely harder on the body than grass.”

The survey asked the players several questions about their marijuana use. Eight players said they were daily smokers back in the day, while the rest reported sparking up “occasionally.” A small majority of responders said they still smoke today. Those who don’t partake had various reasons: They have grandkids now. They live in a state without legal medical or recreational marijuana. One player gave up pot because it made him paranoid. The ex-quarterback said he “participated in the fad of it and lost interest in it thereafter,” going cold turkey in 1980. Banks had to stop in 1995 because of mandatory drug testing at a new job.

Most respondents said that pot allowed them to cope with pain after a game.

“Weed helped me,” Dobler said. “It put me in a state where I didn’t give a shit how I felt after we played.”

The ex-running back said, “When I smoked after a game on Monday, I didn’t feel as beat up as usual.”

Banks agreed: “Pot helped me relax … and it eased the pain.”

The ex-quarterback said he used cannabis “maybe to relax after games and heal for a day or two.”

Back then, hardly anybody was consciously aware that cannabis had medicinal benefits. The ex-running back, the only survey responder who knew about medical marijuana, grew up in the Bay Area and started smoking pot in the early 1960s. Even with today’s medical marijuana acceptance by a majority of Americans, several responders remain dubious, but most of them want their union —the National Football League Players Association— to support the use of medical marijuana, especially in states that have legalized cannabis.

Dale Hackbart lives in Colorado and gets CBD from a dispensary. “At least let players who’ve had concussions use it,” he said. “They don’t even have to smoke. They can make brownies. Really, pot [use] should be as common as going out for a beer.”

In the meantime, NFL players past and present will have to confront an ominous reality. Frontline reported in 2015 that neuropathologist Ann McKee had examined the brains of 91 deceased NFL players, and 87 showed signs of CTE. (The extremely high percentage reflects the fact that most of those men, while alive, had symptoms that led them and/or their families to contribute their brains for study by researchers.)

For decades the NFL team owners ignored, denied, stonewalled and concealed scientific evidence linking concussions to CTE. Nor did the owners ever warn their employees about the severe neurological risk of playing football. So players took the NFL to court. In the last few years, judgments in class-action lawsuits representing thousands of players have gone against the NFL, which will have to pay billions of dollars in benefits to qualifying players. Five players in our survey have said they applied, while several others are considering it.

The NFL also ignores evidence of the medical usefulness of marijuana. The league’s current just-say-no stance on weed forces players to use pills and alcohol, which ae both way more harmful than pot. If our anecdotal evidence suggests a protective effect, it may hasten the day when players can use marijuana to help them ward off neurodegenerative disease.

From Anecdotes to Data According to neurologist Allan Bernstein, MD, “There may be a protective effect of cannabinoids on concussed brains, but we don’t have a reproducible model to meet the usual medical criteria.

“Most people with CTE don’t even know they have it until the symptoms are too severe to ignore, It is a little like Alzheimer’s, which I am actively studying; the changes in the brain may precede the symptoms by five to 15 years. We use a PET scan for amyloid [clumps of protein], a specific marker that enables us to diagnose ‘prodromal’ Alzheimer’s disease in people without symptoms. We don’t have that marker for CTE yet, but if you did a careful cognitive battery on all the NFL players who consider themselves okay, I think you’d be surprised by their cognitive loss.

“Although it’s not ‘science,’ the St. Louis players’ effort to evaluate their condition(s) is a step in the right direction. There could be a study comparing cognitive abilities of pro football players and college-educated athletes who played non-contact sports. An investigator could locate as many users and non-users from the same pro football era and compare their cognitive levels (taking into account how many years they played, what position, and so forth). They should be comparable, but then the use of cannabis may actually separate the groups.”

Extra Point Considering the NFL’s close ties to the alcohol and pharmaceutical industries, it may take more than a real scientific study to bring back the Golden Age of Ganja.