“I’ve been through a lot, good and bad, I’ve seen governments rise and fall and scientific theories rise and fall, and I think there’s a breadth of mind which, provided the brain is healthy, comes with age.” —Oliver Sacks

Eli Lilly got FDA approval to market Prozac in December 1987. The company had a brilliant strategy for making it a blockbuster: promote not the drug so much as the disorder, “Clinical Depression” —a supposedly widespread “mental illness” that, by the way, Lilly’s new “Selective Serotonin-Reuptake Inhibitor” could supposedly treat.

Lilly’s peer-reviewed publicists made many false claims. A major theme was that millions of Americans were being kept from getting a Depression diagnosis (and proper medication) by baseless shame. ‘Overcome your shame’ worked as a sales pitch then and it’s working still —witness the publication in the NY Times August 5 of “The Great God of Depression,” an article about the novelist William Styron by a woman named Pagan Kennedy. It begins:

Nearly 30 years ago, the author William Styron outed himself in these pages as mentally ill. “My days were pervaded by a gray drizzle of unrelenting horror,” he wrote in a New York Times Op-Ed article, describing the deep depression that had landed him in the psych ward… why, he asked, were depressed people treated as pariahs? A confession of mental illness might not seem like a big deal now, but it was back then.

Not true. Discussion of melancholy has always been acceptable among those who could afford to discuss it. The reason millions of US Americans didn’t make “a confession of mental illness” until Prozac came along is that they didn’t define their unhappiness as mental illness.

In the 1990s I reported on the marketing of Clinical Depression for the Anderson Valley Advertiser, and with Alexander Cockburn, wrote a comprehensive piece on the subject that was rejected by the LA Times. Based on 100 phone interviews (in response to a classified ad in the San Francisco Bay Guardian), we concluded that “Clinical Depression is invariably a function of loneliness and/or insecurity —plain words that suggest social rather than chemical causation.”

We noted that William Styron and Mike Wallace filled an important niche in Lilly’s marketing campaign, being prime examples of men who were famous, respected, well-to-do… and yet prone to Clinical Depression! Both Styron and Wallace suffered from loneliness, broadly defined. Styron’s beloved mother died when he was 13 after a many-years-long ordeal with cancer. Boys who watch their mothers suffer and then lose them can feel the loss forever. That’s not a medical disorder, it’s grief that can never be resolved. Mike Wallace’s handsome, talented son Peter died at age 19 in a mountain-climbing accident. Was the father’s enduring grief an illness?

Psychiatrist Frederick Goodwin, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health explained in a phone interview that an episode of major depression is one of “relentless duration —week after week. You can have a grief reaction that can be every bit as intense as a clinical depression. But it doesn’t last. Depressions stick around…” A key to defining depression, Goodwin reiterated, was “duration, measured in weeks and months rather than days.”

Cockburn and I wrote: “Weeks and months? Is that ‘relentless duration?’ We don’t know about you and your friends and patients in Washington D.C., doctor, but in our circles grief reactions last for years, decades, lifetimes, generations!”

Reading “Darkness Visible” years ago I was very surprised to learn that William Styron didn’t see himself as a man who had been affected by fear and sadness. His first novel, “Lie Down in Darkness,” is excruciating. His best-seller, “Sophie’s Choice,” was grim, to put it mildly. My favorite, “Set This House on Fire,” is his lightest —but it’s pretty heavy. “Darkness Visible” is s stylishly written memoir, not dark in tone until page 83 when Styron describes the death of his mother and his unresolvable loss, grief, and rage get expressed. Who told him that how he felt was “mental illness.”

I met Styron and his wife Rose in the 1960s through their Martha’s Vineyard neighbor, Lillian Hellman. I was interviewing Hellman for a possible book. I remember Styron being devastated when “The Confessions of Nat Turner” got dissed by Black intellectuals. The admiration of classy friends was no consolation. I stopped visiting Hellman in ’71, she died in ’84, and I don’t know to whom Styron turned as sadness overcame him in life. He needed honest feedback from a sensible friend; instead he got treatment from a “brain scientist.” Pagan Kennedy writess:

“His famous memoir of depression, ‘Darkness Visible,’ came out in October 1990. It… demonstrated that patients could be the owners and describers of their mental disorders, upending centuries of medical tradition in which the mentally ill were discredited and shamed. The brain scientist Alice Flaherty, who was Mr. Styron’s close friend and doctor, has called him “the great god of depression” because his influence on her field was so profound. His book became required reading in some medical schools, where physicians were finally being trained to listen to their patients…

This past year, I have been working on an audio documentary about Mr. Styron and Dr. Flaherty (a longtime friend of mine).

Pagan Kennedy (@Pagankennedy) is the co-producer of “The Great God of Depression,” a serial podcast from PRX’s Radiotopia; the author of “Inventology: How We Dream Up Things That Change the World”; and a contributing opinion writer.

The Anti-Depressant Epidemic

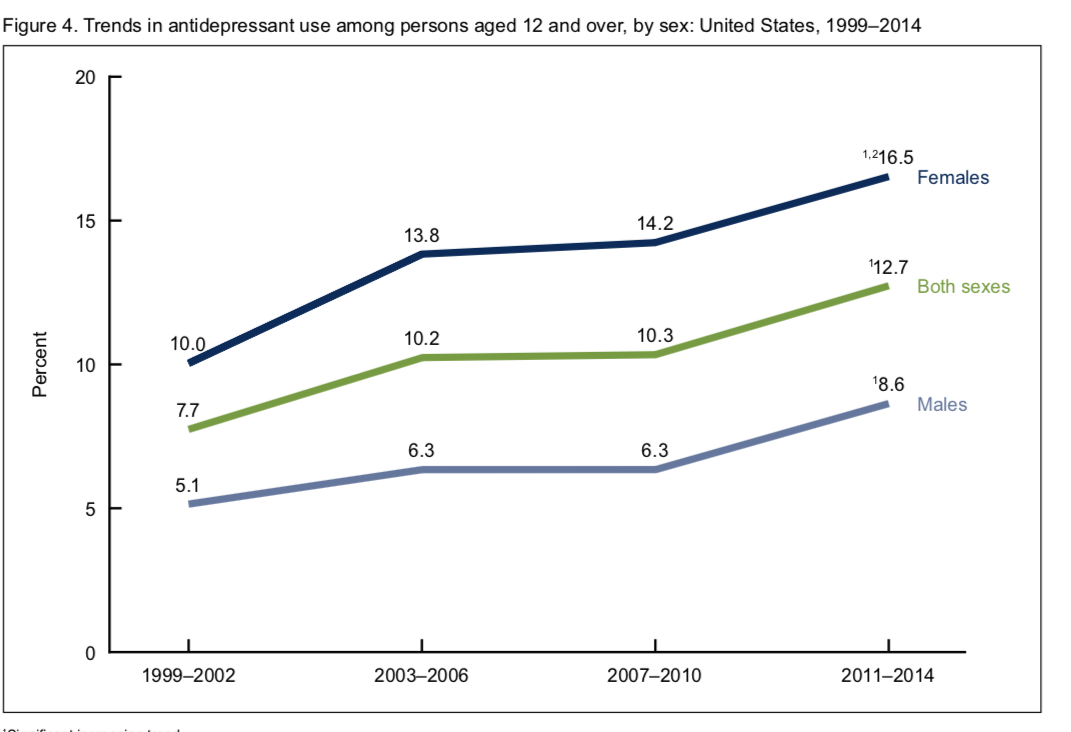

We tend to think of the 1990s as the Prozac Decade, but sales have continued soaring ever since. Between 1999 and 2014 antidepressant use in the US rose by 65%, according to a US Center for Disease Control and Prevention study.

By 2014 about one in eight Americans over age 12 reported recent antidepressant use. Women were about twice as likely as men to be using. A quarter of the people who had used in the past month had been on anti-depressants for 10 years or more.

When the CDC report came out, CBS News asked a New York psychiatrist named Ami Baxi to explain the steep, steady rise in anti-depressant use. Baxi credited FDA approvals for more indications and “a sign of decreasing mental health stigma,” where more people feel comfortable asking for help against depression and anxiety.” More people overcoming shame and taking antidepressants! Progress!

Why should this matter to cannabis clinicians?

The medical marijuana movement/industry has been the accidental beneficiary of Big PhRMA’s campaign to promote Prozac and other SSRIs. For three decades the American people have been taught that there is a medical disorder called Clinical Depression that results from a chemical imbalance in the brain and is treatable by drugs. Physicians have been taught to prescribe anti-depressants readily. (The political implication is that the spreading mass misery is just so many individual cases of ‘chemical imbalance,’ correctable by drugs.)

The use of anti-depressants —including cannabis— can divert attention from the causes of a person’s unhappiness. The responsible cannabis clinician issuing a Depression (or Anxiety) diagnosis should discuss with the patient the possible source(s) of his or her “disorder.” He or she may not be able to improve on their situation, but identifying the source(s) of unhappiness is a step in the right direction. Cannabis should be used to cope and understand, not to obfuscate and deny.

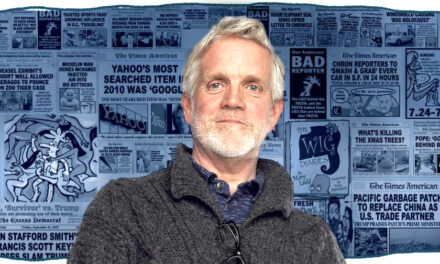

—Fred Gardner