In 1996, his first year in office, Terence Hallinan was the only district attorney in California to call for a “yes” vote on Proposition 215, the initiative to legalize the medical use of marijuana. (Even Norm Vroman, Mendocino’s libertarian DA, had opposed Prop 215.) Hallinan had promptly fired the Assistant DAs least likely to adopt his lenient approach to charging nonviolent violations of the drug laws, but he could not change the priorities of SFPD’s narcotics unit.

The narcs, who could pass for sleazy addicts when they worked undercover, were hard to miss around the Hall of Justice in their Hawaiian shirts, which they sported like gang members showing their colors. Terence first clashed with them when he instructed SFDA prosecutors not to rely on evidence from “buy busts.” The widely used tactic involved an undercover cop going out, usually to the Tenderloin, to sell or buy a small amount of drugs, usually crack, the form of cocaine favored by Black people, while four or five other undercover cops observed the transaction from across the street. Buy busts generated a tremendous amount of overtime for the cops, who got paid for the hours spent testifying and waiting to testify. The Public Defenders pled everybody out to six-month sentences and the judges appreciated the speed with which such cases were disposed of. From Hallinan’s POV, the victims were people he didn’t want to target in the first place and the recidivism rate was high. He started a program to offer diversion to people arrested for crack violations. (Crack was the form of cocaine favored by Black users.) The resentful narcs, led by Captain Greg Corrales, started bringing cases directly to the feds, who did not want to pursue them.

The SFPD had conducted an undercover investigation of Dennis Peron’s SF Cannabis Buyers Club and brought SFDA evidence that numerous felonies were committed there every day. When SFDA declined to prosecute, Corrales went to California’s Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement, which was under Attorney General Dan Lungren, an arch prohibitionist. The BNE then conducted its own three-month investigation, which involved techno-surveillance (including a helicopter!) and agents going to elaborate lengths to gain membership. They forged letters of diagnosis on fabricated doctors’ letterheads and even set up phone lines so that a club registration worker, calling to confirm a patient’s letter, would reach an agent at BNE headquarters pretending to be the receptionist of a doctor with a Japanese name. (Tod Mikuriya, MD, was widely known as a Cannabis proponent.)

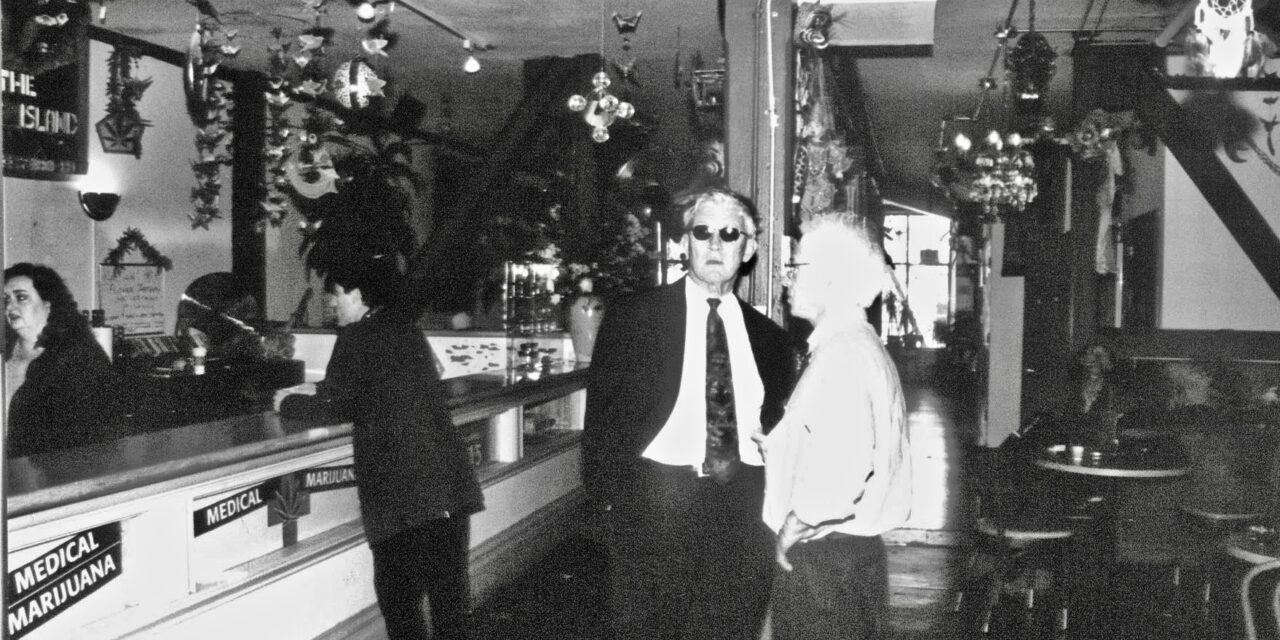

In June ’96 Hallinan visited the club himself and advised Dennis to stop allowing members to bring guests. I was working at UCSF at the time and free-lancing. I had successfully pitched a piece about the Prop 215 campaign to the New Yorker, and interviewed Terence about his decision not to prosecute the SFCBC. Dennis, he said, acknowledged that he was making a profit, “less than people thought —remember, he had to buy all this marijuana— but his numbers added up in terms of what he said he spent and what he made and what he paid his employees and what he put back into the club. He claims the money they made was going to buy a place on the Russian River, a resort for the club members. Is he a profiteer? We see no evidence of that. He lives with a bunch of people in a small house, he doesn’t have a new car, he doesn’t take vacations, he doesn’t have a big family that he’s trying to leave a fortune to. He says ‘The club is my family.’’

The BNE proceeded to raid and shut down the club in the wee small hours of Sunday August 4. The front door was battered in and the raiders hung black drapes over the windows to hide what they were doing from civilians on Market Street. Approximately 100 agents wearing black uniforms with BNE shoulder patches, supervised by Senior Assistant Attorney General John Gordnier, seized 150 pounds of marijuana, $60,000 in cash, 400 small plants growing under lights in the basement, plus thousands of letters of diagnosis that citizens had brought from their doctors and left on file at the club. Five smaller BNE squads raided the homes of Buyers Club staff members in and around the city.

District Attorney Hallinan and Mayor Willie Brown had no advance notice of the raids and expressed outrage. “It was strange not seeing any San Francisco police,” remarked Basile Gabriel, one of the employees detained for questioning. “It felt like the state had invaded the city.” The San Francisco Medical Society protested the confiscation of medical records as a violation of doctor-patient confidentiality. Dennis Peron charged that closing him down was “step one in Lungren’s No-on-215 campaign. It was timed to kick off the Republican convention in San Diego. They want to make the war on drugs a big issue because what else have they got?”

Lungren’s effort to make the Prop 215 vote a referendum on Dennis Peron’s right to operate backfired. California voters passed the initiative by a 56-44 margin on November 5, 1996. At 12:01 a.m. on November 6, faxes and emails went out from Attorney General Dan Lungren, summoning every DA, police chief, and sheriff in the state to Sacramento December 4 for an “Emergency All Zones Meeting” at which the AG would explain his “narrow interpretation” of the law created by Prop 215.

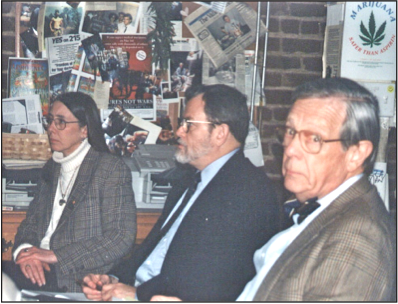

My New Yorker piece had been spiked at the urging to Mitch Rosenthal, MD, owner of the Phoenix House chain of treatment centers. The “kill fee” was a lot more than I was ever paid for an article before or since. I decided to stay on the medical marijuana story and started compiling a chronology called “The Year of Implementation.” When I got wind of Lungren’s Emergency All-Zones Meeting, I arranged to ride out to Sacramento with Terence that morning so I could debrief him on the ride back. An investigator from the DA’s office did the driving. As we were pulling up in front of the downtown Hilton, Terence said, “Why don’t you come in with me? I’ll say you’re my ‘policy aide.” And so I accompanied him to the meeting.

The vast ballroom was buzzing as some 350 law enforcers waited for the show to begin. When Terence entered, the place became quiet. We walked all the way to the third row and found two seats that happened to be right behind the DA of Sonoma County, Mike Mullins, who had been my customer at Variety Home Video in Kenwood. I was telling Terence that he was responsible for Mullins’ long and happy marriage. Mullins had been a lieutenant in the MPs and was guarding the Presidio from a throng that Terence had led to the gates, among them a young woman named Liz, who engaged Mullins in conversation… Before Mullins could confirm or correct my recollection, two beefy men in plain clothes waved for me to join them in the aisle. They asked to see my star. Terence told them, “He’s my policy aide.” One of the large men said, “This is law enforcement only.” I got the silent treatment again as I was led down the aisle. I thought about telling them all, “Now don’t be sore losers.” But kept my mouth shut.

Driving back Kayo said his request for speaking time had been relayed to Lungren by John Gordnier, who seemed surprisingly supportive but the answer was no. So he used the question period to say his piece, which was, “Implementing this law should be left up to your public health departments. That’s what we’re doing in San Francisco. Spare yourself the problem.” He said he got nods of understanding from two or three other DAs. |Kayo said he encountered Lungren during a coffee break and the AG, trying to be affable, said, “I want you to know that I’m half-Irish.” Kayo responded, “Yeah, but the wrong half.”

A Commie Conspiracy to Weaken Prop 215?

Two different sets of ballot arguments in support of “the Compassionate Use Act of 1996” were submitted for publication in the Voters’ Handbook. Unsurprisingly, the Republican Secretary of State rejected the arguments submitted by Dennis Peron and printed those that had been drafted by Bill Zimmerman, the Santa Monica PR man funded by George Soros and other enlightened billionaires to manage the Prop 215 campaign. The argument Zimmerman drafted for Terence Hallinan stated to sign stated “Police officers can still arrest anyone for marijuana offenses. Proposition 215 simply gives those arrested a defense in court if they can prove they used marijuana with a doctor’s approval.”

As worded by the authors of Proposition 215 — Dennis, Dale Gieringer, Bill Panzer, Tod Mikuriya, Valerie Corral, and other grassroots activists who provided input— Prop 215 was a bar to arrest and prosecution. Its stated purposes included “ (B) To ensure that patients and their primary caregivers who obtain and use marijuana for medical purposes upon the recommendation of a physician are not subject to criminal prosecution or sanction.”

But Zimmerman’s ballot arguments enabled California judges to define the law created by Prop 215 as (merely) providing an affirmative defense. Cops could keep busting, DAs could keep charging, and the accused could cite “medical use” in court.

The No-on-215 arguments had been signed by the president of the California District Attorney Association, the medical director of a rehab facility, and the “red ribbon coordinator” from Californians for Drug Free Youth, Inc. They stated: “READ THE FINE PRINT. Proposition 215 legalizes marijuana use for ‘any other illness for which marijuana provides relief.’ This could include stress, headaches, upset stomach, insomnia, a stiff neck… or just about anything.”

Following the passage of Prop 215, prosecutors frequently challenged defendants’ diagnoses, forcing doctors to appear in court. Why were the “No-on-215” ballot arguments ignored by the courts while the “Yes” arguments were cited as definitive? Because “Yes” arguments are considered indicative of the framers’ intent. Which is reasonable but in the case of Prop 215, the grassroots framers had been replaced by the professional reformers.

Flash forward to 2000, when I was SFDA’s public information officer and Zimmerman was promoting a “treatment-not-incarceration” initiative that Kayo was going to endorse. Zimmerman came to the Hall of Justice to help plan a forum that our office was organizing in support of the initiative. Before he left he gave Kayo the ballot argument to sign, which Kayo did unhesitatingly and with barely a glance. Also present at that meeting was Kayo’s chief assistant, Darryl Saloman, who asked —as soon as Zimmerman stepped out the door— what he had just signed. Kayo said it was a ballot argument in support of Zimmerman’s initiative. Salomon was appalled and said, “How can you just sign something so important without reading it?” Terence told him, “Oh, I go back a long way with Bill Zimmerman. He was in the DuBois Clubs.”

I wondered if Darryl Saloman knew that the DuBois Clubs were a youth group loosely aligned with the Communist Party. And I wondered if Terence had signed the ballot arguments for Prop 215 in the same trusting way.