By Fred Gardner

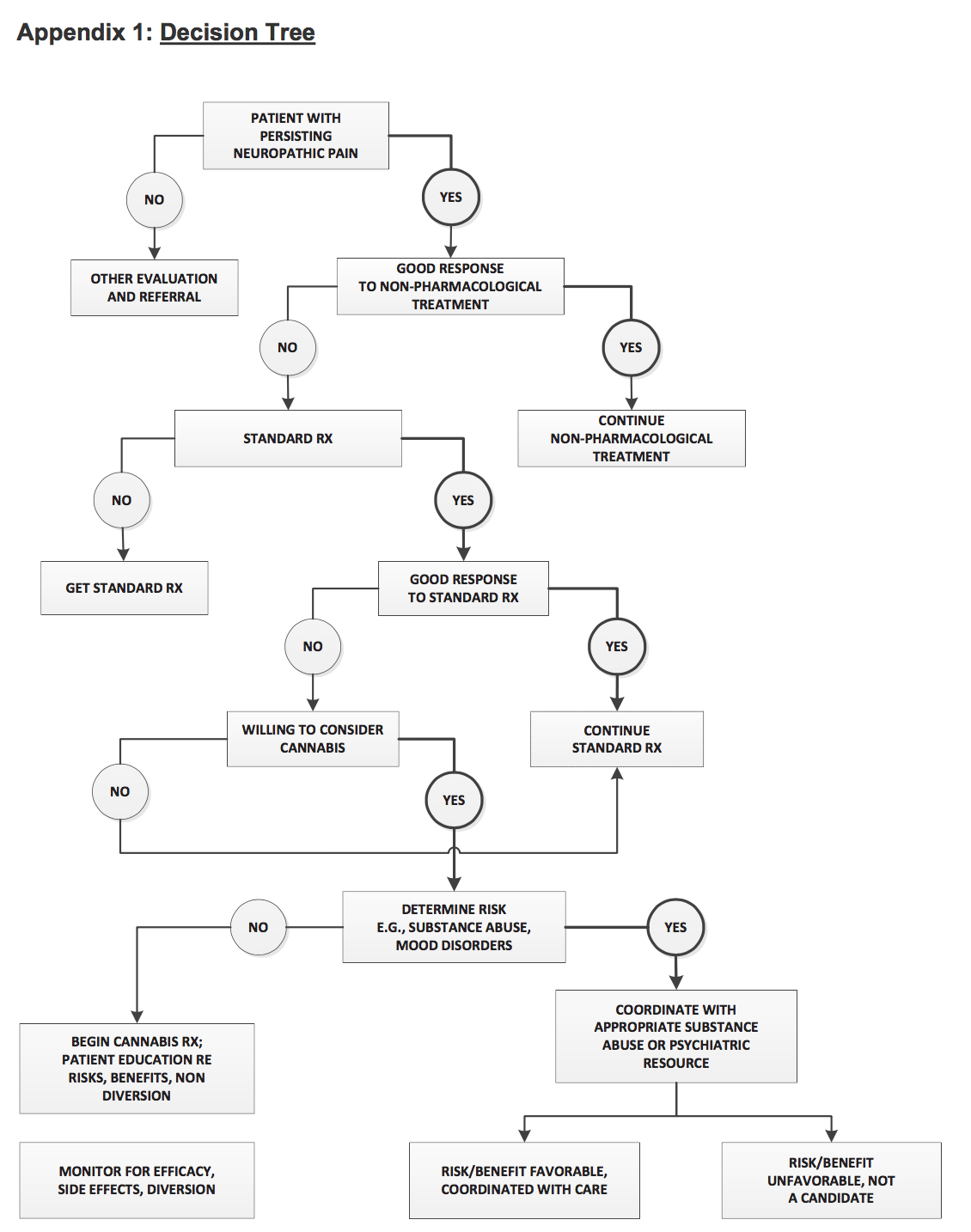

The Medical Board of California (MBC) at its October 27 meeting voted on new Guidelines for the Recommendation of Cannabis for Medical Purposes with two appendices that practitioners might find useful. Appendix 1 is a “Decision Tree” that violates an important tenet of the Guidelines adopted by the board.

This ruptured appendix is a clear case of bureaucratic malpractice. The Guidelines state, “A patient need not have failed on all standard medications in order for a physician to recommend or approve the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes.”

But the “Decision Tree” makes cannabis a treatment of last resort after “Standard Rx” has been tried! How many California physicians —having learned nothing about cannabis or the endocannabinoid system in medical school— will rely on the handy “Decision Tree” in treating pain patients? How many pain patients will be steered to opiates as a first option?

The medical board was directed by the California legislature (when it passed SB-643 in 2015) to adopt practice guidelines for cannabis-approving physicians based on input from the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research (CMCR) at UC San Diego. The med board created a two-member Medical Marijuana Task Force —LA ophthalmologist Howard Krauss, MD, who has never approved cannabis use by a patient, and Kristina Lawson, a land use attorney who is a former mayor of Walnut Creek. (If Lawson filed two contradictory documents on behalf of a private client, it would be a professional embarrassment, and possibly costly.) The task force was advised by CMCR Director Igor Grant, MD, and his fellow psychiatrist Barth Wilsey, MD, to include the neo-prohibitionist “Decision Tree” and an “Agreement” by which cannabis-approving physicians can get patients to acknowledge the looming dangers. The “Agreement” was modeled by its CMCR authors on one that pain patients sign when getting opiate prescriptions.

The med board does a good job of webcasting its meetings, and the October 27 MJ Guidelines discussion is online here. Medical cannabis users and concerned citizens should check it out —Webcast 2, starting at 1:09 and lasting till 1:42. The silencing of Dr. Robinson at the end is poignant and revealing.

Lawson, Krauss and MBC Executive Director Kimberly Kirchmeyer repeatedly noted at the October 27 meeting that the Decision Tree and Agreement are “not requirements, but useful tools…” Methinks they doth protest too much. Imagine your employer coming by your desk four times in a day and to casually remark, “This is just a suggestion, not a requirement…” The med board has the equivalent of hire/fire power over California physicians to whom it issues licenses that it can suspend or revoke. No physician wants to be investigated by the board’s Enforcement Division. Most who approve cannabis use by patients are apt to think, “If following this Decision Tree and getting patients to sign this Agreement will make the med board happy, why not?” (The downsides include conveying disinformation and treating the patient like a child.)

Brad Wilsey said flat out, “This agreement is just to allow patients to see some of the harms that may occur.” Krauss. extolled the “Agreement,” suggesting —with just a wee hint of menace— that doctors who get patients to sign will gain a measure of legal protection.Krauss:

“One of the things I appreciate is that these are not being suggested as requirements but guidelines. And although I have never written a medical recommendation for cannabis, as I reviewed these guidelines, it seems to me to be a terrific document that I could commend to physicians to consider using because it fully informs the patient and there are some cases we know where complaints and litigation may follow a physician-patient interaction. So I think at the same time it documents the process of informed consent, which is appropriate to the law. So while it’s not a requirement, I think it’s a great service for us to provide this to physicians…

The misleading, one-sided Agreement is a great disservice to hundreds of thousands —maybe millions— of Californians who will be checking out cannabis as a treatment option in the years to come. (Krauss predicted that legalization would reduce the number of cannabis users seeking physician approval. Maybe. But demand for the true specialists is likely to rise.)

Med board member Michelle Anne Bholat, MD, made the very practical suggestion that the MBC website should include resources for physicians seeking to educate themselves about cannabis-based medicine.

Also practical was a question from Katherine Feinstein —a fair-minded, humane San Francisco judge, now retired— who didn’t understand why UC Medical Center physicians, who are employed by the state, could not issue cannabis approvals to patients. Sharon Levine, MD, said it was probably out of fear that federal funding could be cut off. Levine also noted that the “Agreement” improperly used the word prescribe (instead of recommend).

A representative of the California Medical Association said the “Agreement” should clearly state that its use by physicians was “optional.” She opined diplomatically that the Guidelines were disorganized and flawed. The CMA thinks the MBC line on cannabis use by pregnant should echo the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: do not. Krauss moved that the Guidelines be adopted without the Agreement, which the task force will rework before the board meets in January. The yes vote was unanimous.

The discussion ended around with Steve Robinson, MD, on the phone, pointing out the contradiction between the wording of the Guidelines and the Decision Tree. He was interrupted by attorney Kerrie Webb after exceeding his three minutes by seven seconds, and then and cut off by Kirchmeyer and board president Dev GnanaDev, MD. Not one of them showed any interest in the crucial point Robinson was making. (It’s around the 1:41 mark.)

The Society of Cannabis Cliuicians will try to get the Decision Tree corrected when the Board meets again in January.

“All that needs to be done to the Decision Tree,” Robinson points out, “is moving the choice point of ‘willing to consider cannabis’ up from the fifth-tier decision level to the third-tier decision level, on par with ‘Standard Rx.'”

For now the neo-prohibitionist flowchart is online as Appendix 1 of the Medical Board of California’s Guidelines for the Recommendation of Cannabis for Medical Purposes.

Why the ‘Agreement’ is so Important to the Neoprobes: They Have to Have Harm

“Successful doctor-patient relationships are characterized by candor and trust,” Tod Mikuriya, MD, wrote soon after California voters legalized cannabis for medical use in 1996. “Removing the stigma of criminality promotes candor and trust.”

Mikuriya thought that the doctor’s “parental role” in the traditional doctor-patient relationship was counter-productive. The written “Agreement” being promoted by the Medical Board of California re-enforces the doctor’s “parental role.” Mikuriya was writing in reference to patients substituting cannabis for alcohol, but his approach applies to pain patients seeking to reduce opiate use:

“Treating alcoholism by cannabis substitution creates a different doctor-patient relationship. Patients seek out the physician to confer legitimacy on what they are doing or are about to do. My most important service is to end their criminal status —Aeschlapian protection from the criminal justice system— which often brings an expression of relief. An alliance is created that promotes candor and trust. The physician is permitted to act as a coach —an enabler in a positive sense.”

The MBC’s fear-inducing “Agreement” re-enforces the notion of cannabis as a dangerous drug, easily abused. This inflated dangerousness “justifies” the complex, onerous regulations that politicians at the state and local levels have been enacting in California. The bureaucrats and law enforcers would not have been able to turn legal marijuana into a job creator and moneymaker for themselves if the medical establishment characterized its safety profile as relatively benign, akin to that of coffee.

The whole complex structure of marijuana regulation and taxation rests on its characterization as a dangerous drug. Who but the medical establishment leaders could put that one over on the American people?

CMCR director Igor Grant, MD, and his colleague Barth Wilsey are psychiatrists who have been amply funded throughout their careers by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA). The “Agreement” they are pushing in California is really a political document, not a scientific paper. It is a warning to every patient to whom it is presented that cannabis can be very harmful.

Grant is quick to point out, as evidence of his political neutrality and scientific objectivity, that six of six studies conducted by CMCR showed cannabis conferring medical benefit. Well, of course, doctor —cannabis is effective medicine! But by promoting an exaggerated image of its dangers —a safety profile akin to prescription opiates— CMCR does the bidding of prohibitionist politicians and their corporate patrons.

Twenty years ago Tod Mikuriya thought that a patient getting a cannabis recommendation was effectively joining a movement —the medical marijuana movement, in all its aspects— and that the physician was functioning as an organizer. It’s why he pushed himself so hard holding ad hoc clinics up and down the state in the years after Prop 215 passed.

Drs. Grant and Wilsey also understand that the discussion between physician and patient regarding cannabis provides a chance to advance a point of view. Tod’s POV was more respectful of his patients, more egalitarian, less parental.