By Fred Gardner in O’Shaughnessy’s Summer 2003 (page one of the first issue)

Lawyers for Tod Mikuriya, MD, filed a motion April 24 to dismiss the Accusation against him brought by the Medical Board of California.

On May 1 the state Attorney General’s office, as counsel for the MBC, requested a delay in the Mikuriya case, presumably to prepare a response. There will be a hearing on the motion to dismiss July 11 in Oakland. If it is denied, the Berkeley-based psychiatrist says he’s prepared to defend his handling of 17 cases in which MBC investigators claim he departed from a “standard of care.” The file-by-file hearing is scheduled to begin in Oakland Sept. 3.

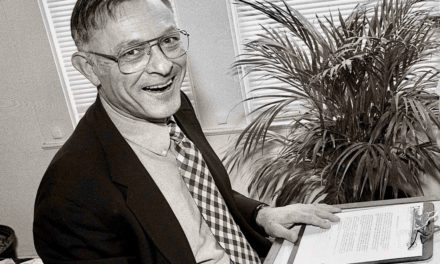

Mikuriya, 69, is a leading authority on the medicinal use of cannabis, having edited an anthology of pre-prohibition scientific papers and reported extensively on his own clinical observations. Since Prop 215 passed in 1996, legalizing marijuana for medical use in California, Mikuriya has approved and monitored its use by some 7,500 patients, many of them seen at ad hoc clinics arranged by cannabis clubs in rural counties.

Many California doctors have been afraid or otherwise reluctant to approve cannabis use by patients whose conditions are not terminal. Mikuriya has been willing to approve its use in the treatment of chronic pain, depression, and a wide range of other medical conditions.

The MBC, which is under the Department of Consumer Affairs, issues licenses to physicians and surgeons —and can suspend or revoke them. The Board has 19 members, appointed by the governor, 12 of whom are physicians. MBC staff Investigators (not MDs, although they can consult “physician experts”), look into complaints and forward cases to the Attorney General for legal action.

No Harm to Patients Alleged

Mikuriya says that not one of the Board’s investigations into cases he allegedly mishandled stemmed from a complaint by a patient or a patient’s loved one. “Nor were any of the complaints from other physicians or healthcare providers,” he adds. “They came from cops and sheriffs and deputy DAs in rural counties who couldn’t accept that a certain individual had the right to use marijuana for medical reasons. And not one of their complaints alleges harm to a patient.”

Mikuriya is represented by his longtime attorney, Susan Lea; Bill Simpich and Ben Rosenfeld —members of the team that sued the FBI on behalf of Darryl Cherney and Judi Bari; and John Fleer, who is retained by Norcal Insurance, Mikuriya’s malpractice carrier.

“We helped him review his files, case by case,” says Fleer. “I’ve been doing this for 20 years and I have a feel for whether a doctor has a detailed understanding of a case. Mikuriya not only had understanding, he had an unusual level of sympathy for his patients… I’m afraid the Board is holding him to an artificially high standard.”

The primary basis for dismissal, according to Mikuriya’s motion, is the section of state law established by Prop 215 (Health & Safety Code section 11362.5) which reads: “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no physician in this state shall be punished, or denied any right or privilege, for having recommended marijuana to a patient for medical purposes.”

Although the MBC investigation is ostensibly about departures from the standard of care, Mikuriya’s defenders say it’s really about medical-marijuana recommendations. A letter to Mikuriya from Senior Investigator Thomas Campbell, dated June 28, 2002, states bluntly, “The Medical Board of California has concluded its investigation into the matter of your treatment and subsequent recommendations and approval of medical marijuana for numerous patients.”

Almost 100 percent of the patients Mikuriya sees had been self-medicating with cannabis before consulting him. He says that the 15-20 minute exams he conducts are sufficient to take a full history, review a patient’s medical records and prior test results, make or confirm a diagnosis, discuss various aspects of cannabis use (he routinely advocates the use of a vaporizer), and note his findings and observations. His initial interviews, he says, “are always face-to-face, in person, confidential, and live.” Follow-ups may be via video, phone, or e-mail. “Successful doctor-patient relationships,” according to Mikuriya, “are characterized by candor and trust. Removing the stigma of criminality promotes candor and trust.”

The Medical Board charges that Mikuriya didn’t establish bona fide physician-patient relationships. “The Board is seeking to hold Dr. Mikuriya to an ambiguous standard of care,” says Lea, “that doesn’t even apply to most primary-care doctors and specialists, let alone doctors acting as medical consultants.”

Ironically, Mikuriya has been imploring the Medical Board since the passage of Prop 215 to develop clear-cut guidelines for doctors who recommend cannabis. This winter he introduced a resolution urging the California Medical Association to lobby the Board to create such guidelines.

Dan Lungren’s Legacy

Mikuriya’s motion to dismiss asserts that the case against him was initiated by “a coterie of federal and state law enforcement officials,” led by former Attorney General Dan Lungren and Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey. Shortly after Prop 215 passed, Lungren instructed California police chiefs, sheriffs and district attorneys to keep arresting and prosecuting citizens for using and cultivating marijuana, and to force their doctors to testify in open court. Lungren then flew to Washington to strategize with the Drug Czar and other federal officials opposed to the implementation of Prop 215.

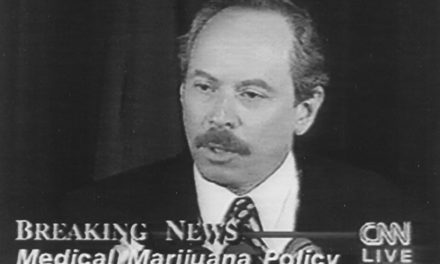

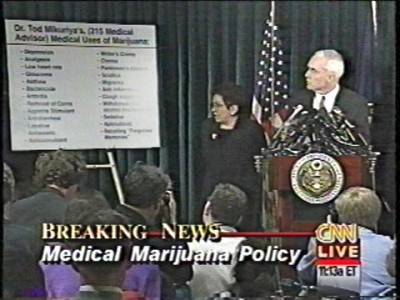

Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey and Health & Human Services Director Donna Shalala ridiculed Dr. Tod Mikuriya’s claim that marijuana was useful in treating a wide array of medical problems at a press conference December 30, 1996 At right (off camera) stood Attorney General Janet Reno and NIDA director Alan Leshner.

On Dec. 30, McCaffrey held a televised press conference at which he warned California physicians that recommending marijuana could cost them their licenses. McCaffrey displayed a long list of conditions for which marijuana reportedly provides relief. It was headed “Dr. Mikuriya’s (Prop 215 Medical Ad-visor’s) Conditions;” McCaffrey ridiculed it as “Cheech-and Chong medicine.”

In response, a group of Bay Area physicians and patients led by AIDS specialist Marcus Co-nant sued the Drug Czar on First Amendment grounds and got an injunction barring the feds from taking action against Calfiornia doctors who “in the context of a bona fide physician-patient-relationship, discuss, approve or recommend the medical use of marijuana.” Mikuriya’s lawyers argue that the Conant injunction “applies with equal force to other government actors, such as the complainants in this case” and provides a second basis for dismissal.

In addition to documents establishing the Lungren-McCaffrey connection, Mikuriya’s lawyers are citing an October 1997 memo from Lungren’s right-hand man, Senior Deputy Attorney General John Gordnier, requesting that district attorneys in all 58 counties notify him of any cases involving medical-marijuana recommendations by Mikuriya and one other physician (Eugene Schoenfeld).

Two of Gordnier’s assistants, Deputy AGs Jane Zack Simon and Larry Mercer, are slated to argue the Medical Board’s case against Mikuriya. “I can’t understand why [current AG] Bill Lockyer would assign these two prosecutors to the case,” says Bill Simpich. “It’s almost as if he’s granting Dan Lungren a last request from beyond the political grave.”

It remains to be seen what penalty the Board would impose if the charges against Mikuriya are upheld, but patients and staff at local dispensaries are fearful. “It seems that Dr. Mikuriya has been targeted for being knowledgeable and outspoken,” says Debby Goldsberry, director of the Berkeley Patients Group. “Patients are afraid of losing his expert care and advice. Everybody’s wondering, ‘Who’ll be next?’”