Introduction Steve Robinson, MD, the president of the Society of Cannabis Clinicians, asked me to set down some recollections of Dr. Tod Mikuriya and the early days of the medical marijuana movement, which I’ve been covering as a journalist for many years. It’s a story with many intertwining aspects —medicine and law, science and politics, history and economics… not to mention personalities.

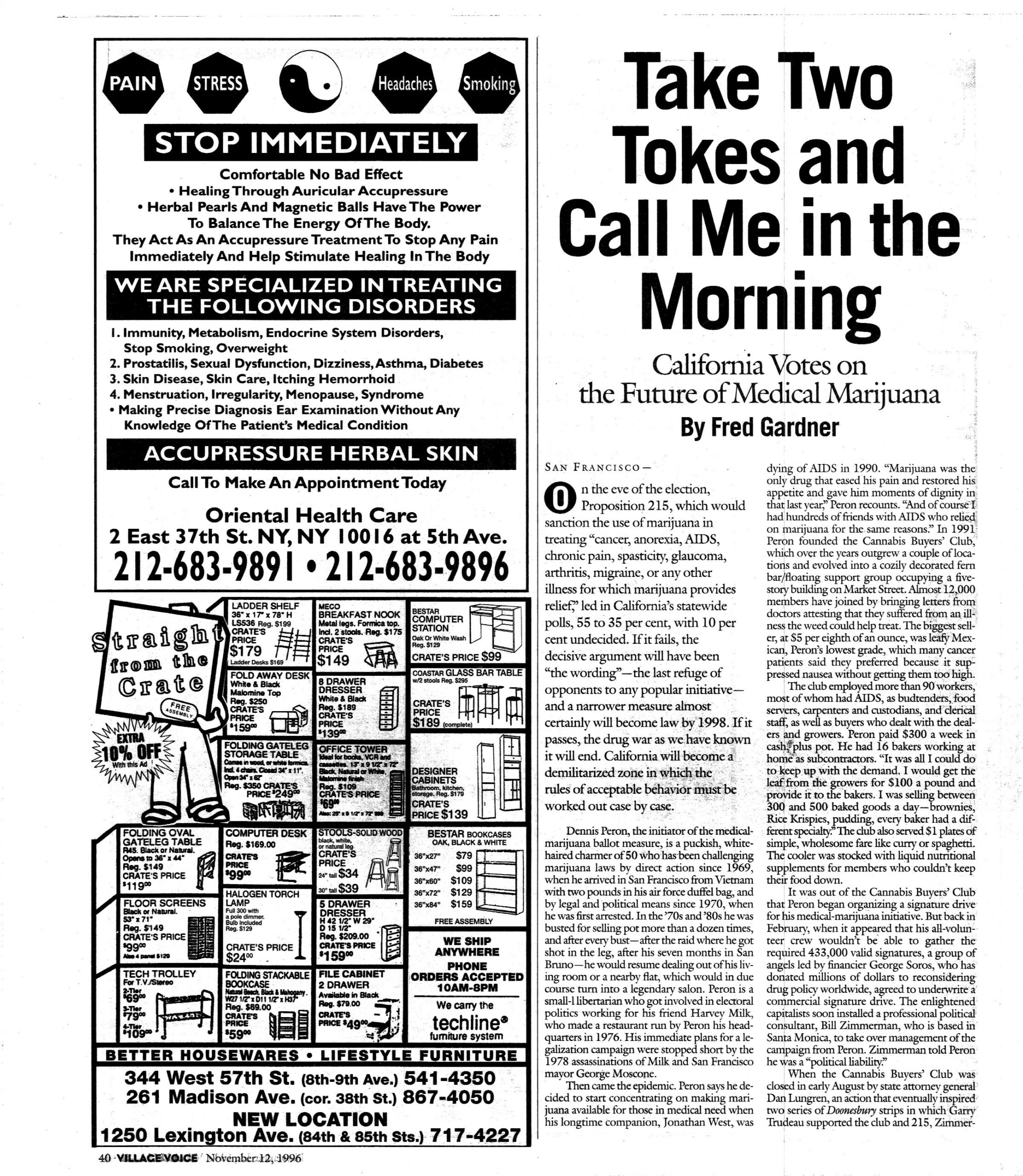

I got involved with the movement from two directions: I knew the prime mover, Dennis Peron, and I had a son with epilepsy. My son is gone now. He was a teenager when he had his first seizure back in the ‘70s. I was working as a private investigator in San Francisco. I went to the library at UCSF Medical Center and found three small studies on marijuana in the treatment of epilepsy. (This was a decade before I worked at UCSF. The library was then in the basement of Cole Hall.) Two papers raised my hopes but another concluded that marijuana use had brought on a seizure. These mixed results made sense to me as a pot smoker and a simpleton, because some pot is energizing and some is sedating. They also dissuaded me from proposing it as a treatment for John.

Recalling my afternoon in the fluorescent basement of Cole Hall, I think: if only I had come across Tod Mikuriya’s book Marijuana Medical Papers I might have started paying close attention to the medical side of the story right then and there! And if I had read the lead article by William Brooke O’Shaughessy, which described the use of Cannabis to reduce seizures, I would definitely have started paying attention!

I wonder if UCSF even had a copy. (Tod had self-published his anthology of the relevant medical literature in 1973.) “It’s not just marijuana that got prohibited,” he used to say, “it’s the truth about history.”

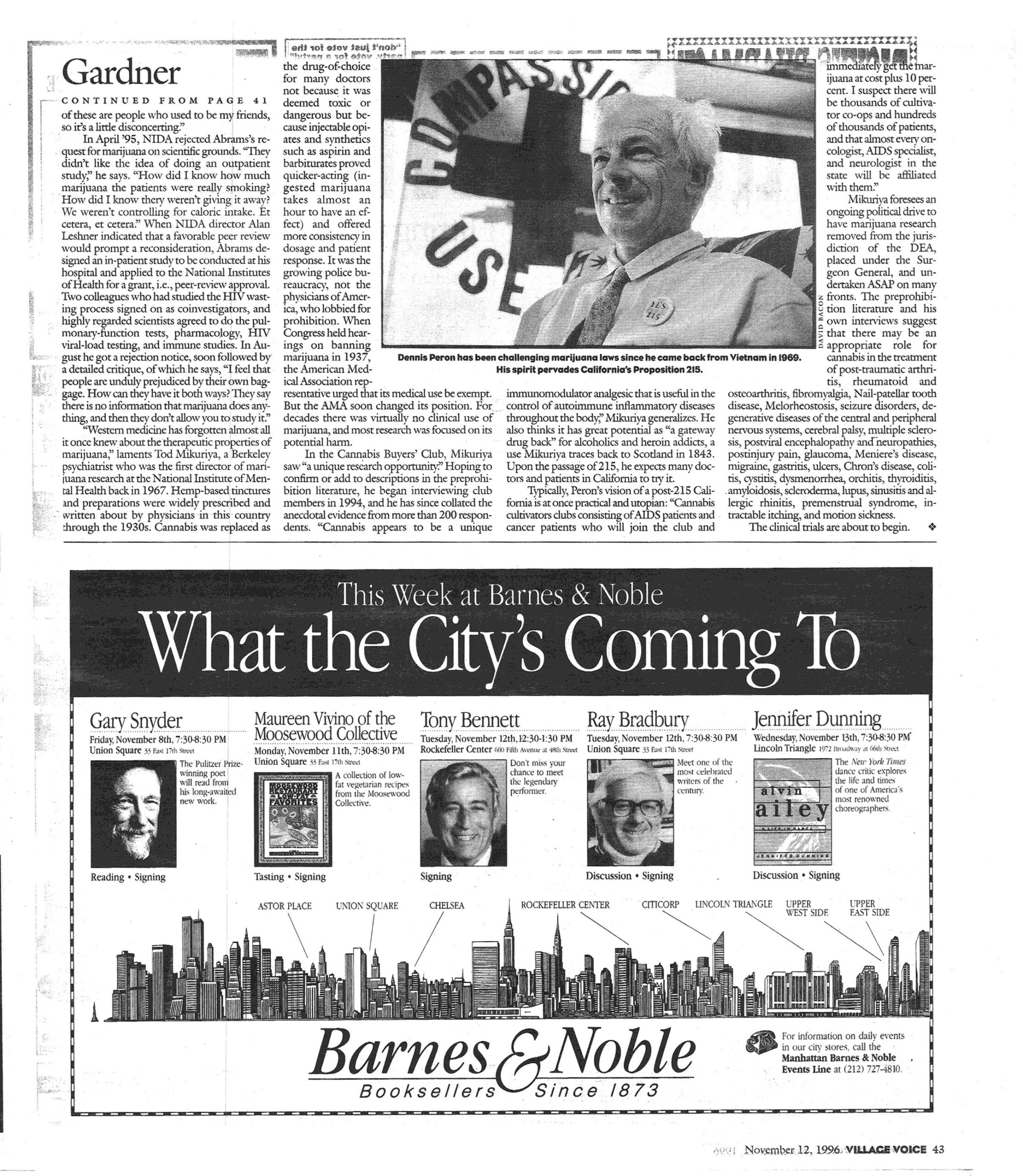

I interviewed Dr. Mikuriya in the summer of 1996 for an article I was writing about the Prop 215 campaign —the California ballot initiative to legalize marijuana for medical use. We hit it off right away. I was then the managing editor of Synapse, UCSF’s internal weekly paper, and moonlighting as a reporter. I got an assignment from the New Yorker to do a piece about Prop 215. Tod was a key primary source. What I learned from him accounted for a good part of my New Yorker piece, which —by the way— was killed at the last minute at the urging of an influential psychiatrist named Mitch Rosenthal, who owned the Phoenix House chain of drug rehab facilities. Repeal of marijuana prohibition was not in his interests.

The New Yorker gave me a kill fee of $3,000 — more than I’d ever made or would make for articles that got published. The Village Voice ran a much shorter version of my piece, which an editor cleverly hedded “Take Two Tokes and Call me in the Morning.” And that’s how the medical marijuana story broke in NYC.

Tod and I became friends and for years would talk every morning, mainly about the medical marijuana movement in its many aspects (science, medicine, law, politics, history, economics, personalities…) and also about world affairs, family matters, everything.

What Tod had to say back in ’96 is strikingly relevant today, as the DEA expands its control over medical research. Quoting from The Voice:

“‘Western medicine has forgotten almost all it once knew about the therapeutic properties of marijuana,” laments Tod Mikuriya, a Berkeley psychiatrist who was the first director of marijuana research at the National Institute of Mental Health in 1967. Hemp-based tinctures and preparations were widely prescribed and written about by physicians in this country through the 1930s. Cannabis was replaced as the drug of choice for many doctors not because it was deemed toxic or dangerous but because injectable opioids and synthetics such as aspirin and barbiturates proved quicker-acting (ingested marijuana takes almost an hour to have an effect) and offered more consistency in dosage and patient response. It was the growing police bureaucracy, not the physicians of America, who lobbied for prohibition. When Congress held hearings on banning marijuana in 1937, the American Medical Association representative urged that its medical use be exempt. But the AMA soon changed its position. For decades there was virtually no clinical use of marijuana, and most research was focused on its potential harm.

“In the Cannabis Buyers Club, Mikuriya saw ‘a unique research opportunity.’ Hoping to confirm or add to descriptions in the pre-Prohibition literature, he began interviewing club members in 1994, and he has collated the anecdotal evidence from more than 200 respondents. “Cannabis appears to be a unique immunomodulator analgesic that is useful in the control of autoimmune inflammatory disease throughout the body,” Mikuriya generalizes. He also thinks it has great potential as a ‘gateway drug back’ for alcoholics and heroin addicts…

“Mikuriya foresees an ongoing political drive to have marijuana research removed from the jurisdiction of the DEA, placed under the Surgeon General, and undertaken ASAP on many fronts. The pre-Prohibition literature and his own interviews suggest that there may be an appropriate role for cannabis in the treatment of post traumatic arthritis, rheumatoid and osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia…”

Tod’s list went on for 37 more conditions, followed by my tag: “The clinical trials are about to begin.”

And now, all these years later, as Capital-M medicine is finally sanctioning some clinical trials, there is no political drive to have marijuana research removed from the jurisdiction of the DEA –the lead agency imposing Prohibition all these years. In fact the opposite is taking place: leading cannabis companies are kowtowing to the DEA, competing to get their products into DEA-controlled clinical trials!

By legalizing marijuana for medical use in 1996, the people of California defied the federal government. How did it happen that the feds took control of the ensuing research?

Remind me to tell you. –Fred Gardner