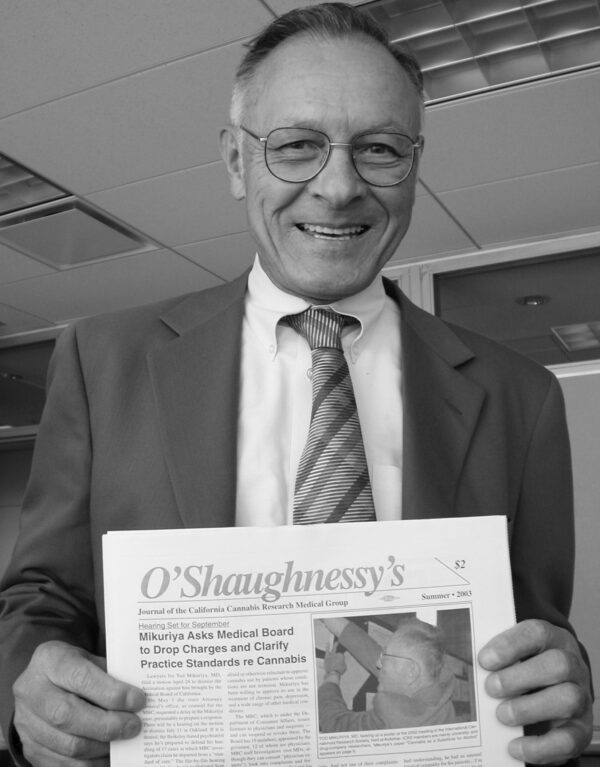

In this, the Year of Evaluating the Evidence, Tod Mikuriya’s insistence on the value of Clinical Evidence —what doctors learn from patients— seems especially relevant. The editorial from O’Shaughnessy’s first issue, Summer 2003, includes one of Tod’s memorable axioms: “Neither human physiology nor the effects of cannabis have changed.” I regret the funky layout of the 1873 Indian Government Report, with its scanned pages of the document Tod had unearthed.—FG

In This Issue

As California physicians take advantage of the unique research opportunity afforded by the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, there is renewed interest in studies carried out in the pre-prohibition era.

The 1873 Indian Government Report evaluating the alleged deleterious effects of cannabis (see page 19) addresses the relationship of cannabis and mental disorder in terms that are relevant in California in 2003.

The report’s conclusion —that the harm caused was small and the tax revenue significant— was affirmed in a massive study 20 years later, The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report of 1893-94.

The IHDC Report was my introduction to the pre-prohibition medical literature on cannabis. In 1966, when I was in charge of setting up research funding patterns and priorities for the National Institute of Mental Health, I ordered and received the eight-volume report from the National Library of Medicine archives. For the next six months I carried the documents with me and photocopied selected sections.

It was only recently, however, that I learned of this predecessor report that in four-and-a-half pages reached strikingly similar conclusions.

Perhaps we in California will come to similar conclusions, too. Neither human physiology nor the effects of cannabis have changed.

The CCRMG is in an optimal position for studying the costs and benefits of longterm medicinal cannabis use. Despite the continuing political controversy surrounding cannabis, actual monitoring and supervision of patients will afford experience to improve treatment of chronic illnesses. —T.H.M.

Statement of Purpose

The California Cannabis Research Medical Group [now The Society of Cannabis Clinicians] was founded by Tod Mikuriya, MD, to enable doctors who have been monitoring their patients’ cannabis use to share data and observations.

Cannabis is not a conventional medicine at this time, and O’Shaugnessy’s —published by the CCRMG— is not starting out as a conventional journal.

Our primary goals are the same as the stated goals of any reputable scientific publication: to bring out findings that are accurate, duplicable, and useful to the community at large. But in order to do this, we have to pursue parallel goals such as removing the impediments to clinical research created by Prohibition, and educating our colleagues, co-workers and patients as we educate ourselves about the medical uses of cannabis.

Some 50,000 Californians have obtained doctors’ approvals to use cannabis since Prop 215 made it legal in November, 1996. (This estimate is based on records kept by cannabis clubs and an extrapolation with Oregon, which has a state program that maintains a registry of patients authorized by physicians to use cannabis.)

Legalization under Section 11362.5 of the state’s Health & Safety Code, created a fearful dilemma for California doctors, because cannabis remained illegal under federal law. Most doctors, having had no training on the subject in medical school, having no guidance with respect to dose, modes of delivery, range of effects, counter-indications, etc., have been understandably reluctant to sanction their patients’ use of cannabis.

A December 1996 threat from federal officials to deny prescription-writing privileges to California doctors who recommend marijuana has achieved some of its inhibiting purpose, although the federal courts ruled that it violated the First Amendment.

Doctors who have approved cannabis use by their patients fall into three broad categories: 1) Willing specialists — mainly oncologists and AIDS specialists who, having been educated by their patients over the years, understood the utility of cannabis and felt confident about approving its use; 2) Willing general practitioners who have written approvals for a few of their patients who have grave illnesses or otherwise undeniable needs; and 3) Cannabis specialists, who recognize its versatility, are convinced of its relative benignity, and keep abreast of the literature with respect to mechanism-of-action, clinical trials in Europe, etc. CCRMG members are in this subset. Collectively, they have issued most of the estimated 50,000 approvals granted to date.

CCRMG members each have their own intake questionnaires and record-keeping systems, and have been slow to agree on a uniform “face sheet” for their patients’ charts (partly because they’ve had to spend so much of their time, energy, and resources responding to legal threats to themselves and their patients).

Six-and-a-half years after the legalization of marijuana for medical use, serious data sharing is only just beginning

Six-and-a-half years after the legalization of marijuana for medical use, serious data sharing is only just beginning; we’re still in the borderland between anecdotal evidence and verifiable data. Nevertheless, the information garnered to date seems worth collating and sharing with other doctors and healthcare workers, as well as patients, caregivers, and concerned citizens.

Political Objectives

Prohibition, as noted, forces us to work in political and legal realms as well as medical and scientific ones. Several specific objectives have been agreed on by the CCRMG. Foremost: reaching an accomodation with the Medical Board of California regarding practice standards.

We would also like to see the Board establish guidelines for its investigators as per the suggestion of Frank Lucido, MD, in his statement to the Enforcement Committee May 8 (see story on page 10). Top priority should go to investigating complaints from patients or their loved ones that allege harm induced by a practitioner. Lowest priority should go to complaints from third parties that don’t allege harm to the patient. Also, the Board should define a standard of “probable cause” that has to be met in order for a complaint to trigger an investigation.

It is a cliché of drug-policy reformers that law-enforcement agents support Prohibition because it provides ongoing employment. That’s simplistic and insulting. We want to see a well-funded Medical Board with a strong Enforcement Division protecting Californians from the frightening array of practices being carried out in the name of medical science.

A skilled, serious team should investigate the integrity of clinical trials financed by pharmaceutical corporations and medical-equipment manufacturers.. Some of the Botox mills that mislead and scar women and men by the thousands might also bear looking into. Are no standards being violated when doctors promote unnecessary surgery?

The MDs and health officials involved in the testing and approval process that led to carcinogens such as MTBE and perchlorate being introduced into our drinking water —did they have any conflicts of interest?

As this issue goes to press EndoVascular Technologies, Inc. of Menlo Park is pleading guilty to federal charges of fraud, having concealed the fact that one of its products —a device used to treat abdominal aortic aneurysms—had malfunctioned thousands of times, resulting in at least 12 deaths. Deadly deception at the corporate level should not escape the attention of the Medical Board of California.

How to Categorize Cannabis?

The CCRMG also has a proposal for California legislators: remove cannabis from Schedule I of the state Controlled Substances Act. Schedule I was created by federal legislators in 1970 for drugs with no medical use; laws in all 50 states then adopted its wording.

The presence of cannabis on Schedule I in 2003 is an intellectual embaras-sment, refuted by our own clinical experience, by investigators sponsored by UC’s Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research, and by the voters of California in their collective wisdom.

Changing the federal Controlled Substances Act may be beyond our reach for now, but the state CSA should be brought into alignment with medical reality (not to mention Health & Safety Code Section 11362.5): marijuana, is useful in treating a wide range of medical conditions.

The question, then, is on which “schedule” of the state CSA should cannabis be placed? Schedule II, which includes addictive morphine and cocaine, doesn’t seem appropriate. The synthetic THC pill, Dronabinol, marketed as Marinol at $8- $10/pill, was moved from Schedule II to Schedule III after lobbying by its manufacturer. But Schedule III includes steroids and strong barbiturates —drugs whose side-effect profile is hardly benign. Schedule IV comprises depressants such as Diazepam and Xanax. Schedule V is mainly for small doses of narcotic drugs mixed with non-narcotic ingredients (like Tylenol with codeine).

Mikuriya has proposed that cannabis be placed in a category of its own, based on its unique mechanism of action. “It should be called an ‘easement,’ he suggests, “not a ‘hypnotic’ or ‘sedative’ as various formularies have it, or a ‘hallucinogen’ as per the federal CSA.” Recent reports that cannabinoids exert their effects by modulating nervous activity make the term “easement” seem all the more apt. Enlightened politicians, please take note. —Fred Gardner and Tod Mikuriya, MD