For months we have all been force-fed a story few of us can digest about the hacking of the Democratic Party’s email servers, presumably by Russians commanded by Vladimir Putin himself. It is unclear how the contents of the DNC emails were supposed to have swayed the US electorate. Was anyone shocked to learn that Mrs. Clinton’s campaign managers were manipulative creeps?

The current brouhaha is utterly trivial compared to the extreme, direct interference by US campaign professionals in the election that solidified Oligarchy in the former Soviet Union.

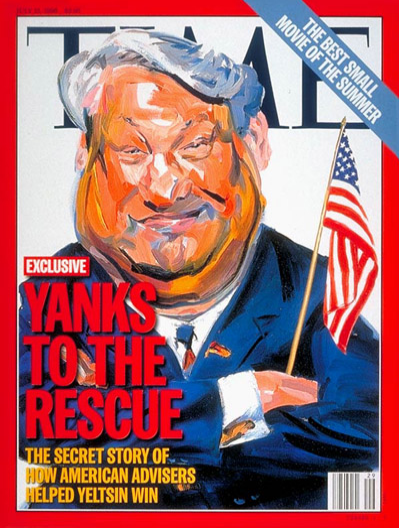

A team of US political consultants operating clandestinely in Moscow was paid $250,000 plus expenses to help a very unpopular Boris Yeltsin get re-elected president in 1996. After Yeltsin’s victory a Time Magazine cover story credited the consultants with engineering it. “Yanks to the Rescue: The Secret Story of how American Advisers Helped Yeltsin Win,” ran the text under a graphic of Yeltsin, slit-eyed, holding a little stars-and-stripes flag.

The story implied that US President Bill Clinton gave the consultants —and Yeltsin— crucial help.

ABC News on “Nightline” also glorified the consultants’ exploits. In due course, so did a Shwotime movie starring Jeff Goldblum.

As reported by Michael Kramer in Time:

…Yeltsin is arguably the best hope Russia has for moving toward pluralism and an open economy. By re-electing him, the Russians defied predictions that they might willingly resubmit themselves to communist rule.

The outcome was by no means inevitable. Last winter Yeltsin’s approval ratings were in the single digits. There are many reasons for his change in fortune, but a crucial one has remained a secret. For four months, a group of American political consultants clandestinely participated in guiding Yeltsin’s campaign…

Kramer identifies Felix Braynin, “a wealthy management consultant who advises Americans interested in investing in Russia,” as the man who pushed to hire US campaign professionals on Yeltsin’s behalf.

Braynin was instructed to “find some Americans” but to proceed discreetly. “Secrecy was paramount,” says Braynin. “Everyone realized that if the Communists knew about this before the election, they would attack Yeltsin as an American tool. We badly needed the team, but having them was a big risk.”

To “find some Americans,” Braynin worked through Fred Lowell, a San Francisco lawyer with close ties to California’s Republican Party. On Feb. 14, Lowell called Joe Shumate, a G.O.P. expert in political data analysis who had served as deputy chief of staff to California Governor Pete Wilson. Since Wilson’s drive for the 1996 Republican presidential nomination had ended almost before it began, Lowell thought Shumate and George Gorton, Wilson’s longtime top strategist, might be available to help Yeltsin. They were —and they immediately enlisted Richard Dresner, a New York-based consultant who had worked with them on many of Wilson’s campaigns.

Gov. Pete Wilson had undergone throat surgery which weakened his voice, and his head wobbled like a bobblehead doll when he spoke. Wilson had vetoed medical marijuana bills passed by the California legislature in 1994 and 1995. Grass-roots activists then drafted the initiative that made the ballot in 1996 as Proposition 215, and changed history.

Dresner had another connection that would prove useful later on. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, he had joined with Dick Morris to help Bill Clinton get elected Governor of Arkansas. As Clinton’s current political guru, Morris became the middleman on those few occasions when the Americans sought the Administration’s help in Yeltsin’s re-election drive. So while Clinton was uninvolved with Yeltsin’s recruitment of the American advisers, the Administration knew of their existence —and although Dresner denies dealing with Morris, three other sources have told Time that on at least two occasions the team’s contacts with Morris were “helpful.”

Dick Morris was Bill Clinton’s campaign manager in 1996. He fell from grace after letting a prostitute (hired so he could suck her toes) listen in on his phone calls with the President. Morris’s wife, Eileen McGann, insisted that he convert to Roman Catholicism and thus the marriage was saved. And now back to Kramer in Time:

A week after the Valentine’s Day call from Lowell, Dresner was in Moscow. The Yeltsin campaign was at sea. Five candidates, led by Communist Gennadi Zyuganov, were ahead of Yeltsin in some polls. The President was favored by only 6% of the electorate and was “trusted” as a competent leader by an even smaller proportion…

To preserve security, a contract was drawn between the International Industrial Bancorp Inc. of San Francisco (a company Braynin managed for its Moscow parent) and Dresner-Wickers (Dresner’s consulting firm in Bedford Hills, New York). The Americans would work for four months, beginning March 1. They would be paid $250,000 plus all expenses and have an unlimited budget for polling, focus groups and other research. A week later, they were working full time…

The person really in charge [of Yeltsin’s campaign] was Yeltsin’s daughter Tatiana Dyachenko, 36, a computer engineer with no previous political experience.

The American team hired two young men, Braynin’s son Alan and Steven Moore, a public relations specialist from Washington, to assist them. and promptly established its office in a two-room suite at the President Hotel. The Americans lived elsewhere in the hotel and were provided with a car, a former KGB agent as a driver, and two bodyguards…

The Americans managed to hide their identity for many months. In interviewing various polling and focus-group companies before hiring three, they described themselves as representing Americans eager to sell thin-screen televisions in Russia. “That story held for far longer than it ever should have,” says Shumate. The Americans carried multiple-entry visas identifying them as working for the “Administration of the President of the Russian Federation,” a bit of obviousness that constantly threatened to undermine all the supposed secrecy surrounding their real work.

The President is not a normal hotel. It is owned by the office of the President, and residence is by invitation only. A fence surrounds the property, which is patrolled by police armed with machine guns and wearing bulletproof vests. When Dyachenko moved her own office to the hotel to be near the Americans, the rest of the campaign took three floors of offices there as well. Yeltsin’s badly split Russian advisers quickly set up separate fiefdoms on the eighth, ninth and 10th floors. Dyachenko worked almost exclusively on the 11th in Room 1119, directly across the hall from the Americans in 1120. She and they shared two secretaries, a translator, and fax, copying and computer-printing machines.

By the end, the team’s office resembled a typical American campaign headquarters. Soda bottles and old food shared space with computer printouts. Graphs charting Yeltsin’s progress in the polls hung on the walls, and the entire scene was dominated by a color-coded map of Russia with Post-it notes describing the vote expected in the nation’s various regions. A safe stood unused, and documents intended for a shredder remained intact, in plain view.

Gorton followed Dresner to Moscow and encountered in Dyachenko a shy, intelligent and idealistic young woman who for some time recoiled at even the most mild American-style dirty trick. “But it wouldn’t be fair,” Gorton recalls her saying when he advised that Zyuganov be trailed by heckling “truth squads” designed to goad him into losing his temper. At their first meeting across a long table covered in green felt, Dyachenko confided, “I don’t know this business. I don’t know what to ask.” For a few weeks, says Gorton, “the task was simple education, Campaigning 101, stuff like the proper uses of polling and the need to test via focus groups just about everything the campaign was doing, or thinking of doing.”

… A great deal of their communication with Dyachenko and Yeltsin’s other aides was conducted by written memorandums. “Translation was a constant problem,” says Dresner. “We spent a full day trying to convey what we meant by having Yeltsin stay ‘on message.'” Minister Borodin says, “Having the memos let the President consider them calmly. We had many discussions about the recommendations and in the end adopted most everything the Americans advised.”

[There was] a campaign-long insistence on a standard American campaign practice —repetition. “Whatever it is that we’re going to say and do,” Gorton explained to Yeltsin’s aides, “we have to repeat it between eight and 12 times.” Those numbers were invented. “The Russians believe that anything that’s worthwhile is scientifically based,” says Shumate. “This gave us a leg up when we started to seriously use focus groups to guide campaign policy, but right at the start it let us pretend that we knew more than we really did. There’s no data supporting how many times something needs to be repeated, but the Russians bought it as gospel.”

… Most Russians, the polls and focus groups found, perceived Yeltsin as a friend who had betrayed them, a populist who had become imperial. “Stalin had higher positives and lower negatives than Yeltsin,” says Dresner. “We actually tested the two in polls and focus groups. More than 60% of the electorate believed Yeltsin was corrupt; more than 65% believed he had wrecked the economy. We were in a deep, deep hole.”

In one of the team’s early memos, a 10-page document dated March 2, the Americans summed up the situation: “Voters don’t approve of the job Yeltsin is doing, don’t think things will ever get any better and prefer the Communists’ approach. There exists only one very simple strategy for winning: first, becoming the only alternative to the Communists; and second, making the people see that the Communists must be stopped at all costs.”

In hindsight, the need for an anticommunist emphasis by the Yeltsin campaign —the need to “go negative”— seems self-evident. But when the Americans first harped on anticommunism as the “only” route to victory, many in the campaign resisted. And despite their status and patronage, the Americans had to fight long and hard before that core strategy was accepted…

In early April Yeltsin gave a major televised speech in which he did not abide by the Americanskis’ advice and did not emphasize anticommunism as his message.

Angry about losing the battle over the speech, and certain it represented a disastrous trend in the campaign, the Americans set out to prove their point after the fact. They replayed excerpts of the address —and some other film footage and still photographs of Yeltsin— for an audience of 40 Russians wired to a “perception analyzer,” an instrument often used in the U.S. Audiences have their hands on dials and are asked to move them in different directions to indicate their degree of interest and approval of what they are seeing and hearing. An electronically produced chart records their reactions.

The results shocked Yeltsin’s Russian assistants… From then on, the American team’s influence grew —and anticommunism became the central and repeated focus of the campaign and the candidate.

Having helped establish the campaign’s major theme, the Americans then set out to modify it. The Americans used their focus-group coordinator, Alexei Levinson, to determine what exactly Russians most feared about the Communists. Long lines, scarce food and renationalization of property were frequently cited, but mostly people worried about civil war. “That allowed us to move beyond simple Red bashing,” says Shumate. “That’s why Yeltsin and his surrogates and our advertising all highlighted the possibility of unrest if Yeltsin lost. Many people felt some nostalgia for what the communists had done for Russia and no one liked the President —but they liked the possibility of riots and class warfare even less.” “‘Stick with Yeltsin and at least you’ll have calm’ —that was the line we wanted to convey,” says Dresner. “So the drumbeat about unrest kept pounding right till the end of the run-off round, when the final TV spots were all about the Soviets’ repressive rule.”

… The Americans were “vital,” says Mikhail Margolev, who coordinated the Yeltsin account at Video International [an advertising firm]. Margolev had worked for five years in two American advertising agencies but freely acknowledges that his methods are still influenced by his earlier tenure as a propaganda specialist for the Soviet Communist Party and as an undercover KGB agent masquerading as a journalist for TASS, the Russian news agency. “The Americans helped teach us Western political-advertising techniques,” says Margolev, “and most important, they caused our work to be accepted because they were the only ones really close to Tatiana.”

… The TV ad the Americans most wanted was the one the campaign made last, which had Yeltsin himself speaking. “We actually wanted him in every spot,” says Gorton. “We wanted the President to come on and say that he understood what they were talking about, that he heard their complaints, that he felt their pain.” But Yeltsin resisted–and that caused the team to reach out to Bill Clinton’s all-purpose political aide, Dick Morris.

Communicating in code —Clinton was called the Governor of California, Yeltsin the Governor of Texas— the Americans sought Morris’ help. They had earlier worked together to script Clinton’s summit meeting with Yeltsin in mid-April. The main goal then was to have Clinton swallow hard and say nothing as Yeltsin lectured him about Russia’s great-power prerogatives. “The idea was to have Yeltsin stand up to the West, just like the Communists insisted they would do if Zyuganov won,” says a Clinton Administration official. “By having Yeltsin posture during that summit without Clinton’s getting bent out of shape, Yeltsin portrayed himself as a leader to be reckoned with. That helped Yeltsin in Russia, and we were for Yeltsin.”

The American team wanted Clinton to call Yeltsin to urge that he appear in his ads. The request reached Clinton —that much is known— but no one will say whether the call was made. Yet it was not long before Yeltsin finally appeared on the tube…

Yeltsin also had problems with his regular TV coverage, even though he essentially controlled the state-run networks… “It was ludicrous to control the two major nationwide television stations and not have them bend to your will,” says Dresner… Beginning in April, Russia’s television became a virtual arm of the Yeltsin campaign, a crucial change that actually came fairly easily. With none of the more democratic candidates breaking through in the polls, most Russian journalists came to regard Yeltsin as the only effective bulwark against the Communists —and thus the best guarantor of their own careers…

Each day brought decisions on details that required careful thought and management. The Americans advised on staging crowds (and government employees were regularly instructed to attend Yeltsin’s rallies). They conceived Russia’s first-ever serious direct-mail effort (a letter from Yeltsin to Russian veterans thanking them for their service). They designed a campaign to use Yeltsin’s wife Naina on the stump, where she was regularly well received. And they fought continuously all suggestions that Yeltsin debate Zyuganov. “He would have lost,” Gorton says simply.

The possibility of Yeltsin losing led his closest aide, General Alexander Korzhakov, to suggest that the election be postponed. Gorton argued against this undemocratic ploy because his polling showed his client leading by 10 points. One wonders how he would have argued if his client had been down 10 points.

… The President’s three democratic opponents had long talked of coalescing behind one or the other of them, and the speculation reached a fever pitch at the beginning of May. Had “they managed that,” says Gorton, “it could really have killed us.” A good deal of time was devoted to strategizing about how Yeltsin could stop the so-called “third force” from emerging.

On election day

A bit of relief came when a CNN correspondent reported that “the only thing voters we’ve spoken with like less than Yeltsin is the prospect of upheaval.” Dresner howled. “It worked,” he shouted. “The whole strategy worked. They’re scared to death!” After months being cooped up in the President Hotel wearing blue jeans, sneakers and PETE WILSON FOR PRESIDENT T shirts, the Americans headed for the building where Russia’s central election commission would be announcing the results as they came in. “The hell with security,” Dresner said. “I want to see this.” And there they sat near the back of the auditorium, six guys in suits with computer projections in their hands and a lap-top computer. The place was overrun with reporters, but Yeltsin’s secret American advisers were never recognized.

The final tally for the first round showed that Yeltsin had edged out Zyuganov 35% to 32% (the Communists had indeed been held to the level they reached in December). Gorton began drafting a memo designed to guide Yeltsin’s remarks, and Dresner began plotting 20 emergency focus groups to determine what voters were thinking. In less than an hour, another memo was written urging the quickest possible runoff date. “We’ve got to try and keep Zyuganov from capitalizing” on the first round’s surprise tightness, Shumate said. “July 3 would be good,” said Gorton. “That’s about as soon as possible, and it’s in the middle of the week so that people will be in town rather than at their dachas.” “We need turnout,” Dresner said over and over.

Why, with unlimited funds, expert advice and the media in his pocket, did Yeltsin win the first round by only three points? The Americans identify several points:

• The continuing underlying hostility toward Yeltsin. “He never overcame the fact that most Russians can’t stand him,” says Dresner…

• A slackening of the Yeltsin campaign’s anticommunist message in the last 10 days. The Americans had advised “that you cannot hit hard enough, or long enough, the idea of the communists’ bringing civil unrest if they win.” In the first round, says Shumate, “the repetition lesson never took completely.”

… The first round’s closeness guaranteed that the two-week runoff campaign would be conducted with care, regardless of the predictions that Yeltsin couldn’t lose. The Americans’ insistence on the anticommunist message was pursued with a vengeance. At the end, Yeltsin’s television advertising was almost exclusively a nonstop diet of past Soviet horrors. Lebed’s law-and-order theme dovetailed nicely with the pre-existing Yeltsin emphasis on preserving stability. Several bogus poll predictions were put forth to make the race seem close and thus increase turnout.

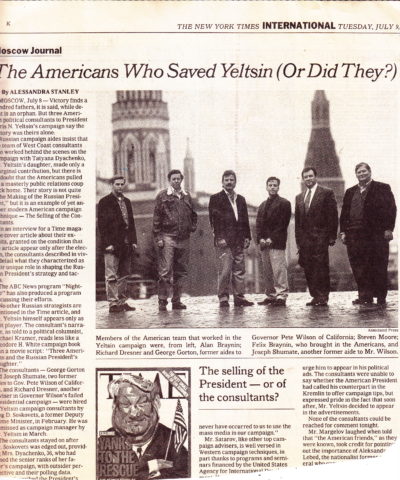

A New York Times story by Alessandra Stanley July 9, 1996, sought to minimize the role the American consultants had played in Yeltsin’s victory. She quoted Russians involved in the campaign portraying Gorton and crew as self-promoters who had not been in on the key decisions.

Stanley revisited the subject in 2004 when Showtime aired a movie, “Spinning Boris,” starring Jeff Goldblum as George Gorton.

She neatly sums up the plot:

In the movie the three men conduct focus groups and quickly realize that Mr. Yeltsin’s only hope is to ”go negative” and paint his Communist opponent, Gennadi A. Zyuganov, as a step back to Bolshevism and unrest. (”It’s the civil war, stupid,” one of them jokes.) Using American tricks of the trade — advance men, planted hecklers and negative ads — the Californians single-handedly devise a winning strategy that overcomes their candidate’s abysmal approval ratings and his habit of appearing intoxicated at public events.

Stanley notes that Gorton, Shumate and Dresner “most recently helped elect Arnold Schwarzenegger governor of California.” She adds her own trenchant commentary on Yeltsin’s triumph in 1996:

The Americans’ poll analysis and focus group research helped shape Mr. Yeltsin’s campaign strategy, but it was money that tipped the balance. The Faustian bargain that reformers like Anatoly B. Chubais made with Russia’s new class of robber barons, or oligarchs, got Mr. Yeltsin re-elected and also spawned a second wave of crooked privatization deals, Kremlin favoritism and media control that discredited Russian capitalism. The reformers perverted Russian democracy to save it, paving the way for the neo-Soviet leadership of President Vladimir V. Putin, whose bid for re-election on Sunday is only nominally contested.

What means “neo-Soviet?”