March 3, 2021 When Ferlinghetti died I thought maybe I should write what I knew about Shig’s accusation. But maybe I shouldn’t. Why tarnish the reputation of a man everybody respected (including me)? I called a friend for advice and he convinced me to let it slide. “You only have Shig’s word for it,” he said. I dropped the idea and felt relieved. Why offend the friends and admirers of Lawrence Ferlinghetti? I’ve offended enough people.

But given my Quixotic delusions, failing to report the rip-off of an employee by a business owner would be dereliction of duty. So, here’s the scoop. In the early ’70s I was working for a book wholesaler, L-S Distributors, which only coincidentally spelled LSD. The owner and boss was Lou Swift, a bearded, white-haired man in his mid-60s who ruled his domain from a wheelchair behind a desk in a small office from which he could see the front door. L-S was located on Post Street, off Geary. Pallets on the ground floor held stacks of magazines, mass market paperbacks, The New York Times and an esoteric mix of other publications.

The four men who loaded the trucks and made deliveries were employees of Lou Swift’s Ellis News company and belonged to the Teamsters Union. Downstairs was a subterranean warehouse of “quality paperbacks” lining the walls and stacked on steel shelves that created four long aisles. The downstairs crew were non-union and made $100 a week. They/we were, with the sole exception of Junior Wilson, either English majors glad to be working around books or political organizers hoping the old man would get their manifestos onto Bay Area news stands, as he had done for The Realist. Mr. Swift, who had the voice of Jehovah, tried to send directives by an internal audio system that Junior Wilson repeatedly disconnected within days of installation.

L-S was a jobber —a secondary supply source for retailers who wanted items in a hurry and/or whose needs were too few to justify placing an order with the publisher. My week was split between working in the warehouse and outside sales, which meant calling on and delivering books to vendors from Sawyers News in Santa Rosa to the De Anza College bookstore in Cupertino.

Shig would visit the warehouse once a week to replenish City Lights’s inventory of paperbacks. He came without a list and slowly cruised the aisles with the shopping cart provided by L-S, pulling books that he thought the bookstore needed or ought to have. The books were arranged by publisher. As I picture him now, Shig was like an artist contemplating the palette and daubing his brush. He knew which books were selling which he wanted to sell. Eight copies of The Art of Sensual Massage. Five Jonathan Livingston Seagulls. Books about Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement from Vintage. Sisterhood is Powerful. Small is Beautiful. A few Andrew Weils, RD Laings, Maslows, Piagets, Houseplants, Nerudas from New Directions… Shig liked to talk about the book trade and the state of the world, and I liked to follow him on his ramble through the merchandise.

One rainy day he was there at closing time and asked if I would mind giving him a ride home. Gladly, said I. On the way he confided that his diabetes had taken a turn for the worse and that he had asked Lawrence to give him his promised share of the business —and that Lawrence had reneged. I left L-S Distributors soon afterwards and didn’t stay in touch with Shig. I had always thought highly of Ferlinghetti (above all for the Prévert translations). I never wrote about what Shig told me, although it wasn’t in confidence, and he knew that I was an unconstrained leafleter. Life went on and on. I myself got ripped off by a partner whose word I trusted, and God knows how many times I’ve seen or heard about it happening to others.

I sent an email to Elaine Katzenberger, the woman who had run the business side of City Lights for many years, asking if there was any truth to what Shig told me way back when. She replied: “As I understand it, the story is complicated. I think it’s more nuanced than that, but there was definitely a misunderstanding and bad feelings on both sides (Shig’s being bitterness, and LF’s being remorse). I’d have to ask you to dig further if you wanted to represent the whole truth of that story, but I do know that it’s true that Shig left feeling angry with Lawrence, and would not ever relent and hear LF out from then on. I’ll see what more I can ascertain and let you know.”

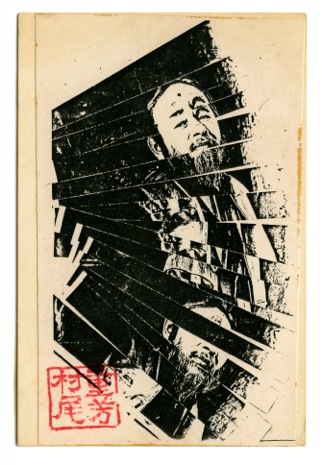

When I watched Shig limp away from my car in 1974, I would not have believed that he had many years of productive life ahead of him. But he did, as recounted in an excellent website created and maintained by his friend Richard Reynolds on the Bancroft Library site. After leaving City Lights (or being driven out), Shig made the Caffe Trieste his hang-out and produced more than 70 issues of a small-batch zine featuring his own poetry, prose and collages. He died in 1999, having expressed his grievances against Ferlinghetti, I assume, to some of his friends in North Beach. My scoop du jour turned out to be no scoop at all. But if you’re looking for negativity, read on.

‘Howl’ Flick Nixes Shig

In 2010 Hollywood gave the world a movie called ‘Howl,’ starring James Franco as Allen Ginsberg, James Rowland as Ferlinghetti and nobody as Shig because Shig wasn’t in the script. Shig was in City Lights, behind the register on the night of June 3, 1957, when two undercover SFPD officers bought a copy of Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg (for 75 cents) and then arrested him for ringing it up. He spent an unpleasant night in jail.

Ferlinghetti, charged as the publisher of an obscene book, turned himself in a few days later. The case was filed as People of the State of California, Plaintiff vs. Shigeyoshi Murao, No. B27083 and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, No. B27585, Defendants. At the end of the trial, Judge Travis W. Horn dismissed charges against Shig because the prosecution hadn’t established that he was familiar with the contents of Howl. The case was renamed People vs Ferlinghetti and the publisher was found Not Guilty on First Amendment grounds.

When Howl, the movie, was being made, Patricia Wakida, a curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, asked the producers about the portrayal of Shig Murao and got no reply. She wrote to them: “It would be blasphemy to leave out the most ironic character in the ‘Howl’ story — the Japanese American who is put into American internment camps, then serves in occupied Tokyo in the U.S. Army, who then becomes the long-time manager of City Lights bookstore and who is actually arrested by the S.F. police for selling ‘Howl’ and actually goes to jail. Ginsberg was in Tangier (Morocco), and Ferlinghetti was in Big Sur. Shig was the one who took the fall.”

Wakida wrote a piece about Shig for the Nikkei West website, describing him as “a Bohemian Nisei” and “a consummate book lover, a confidant for nearly every major San Francisco ‘Beat’ literary figure, the man responsible for creating the very ambience, the ‘soul of City Lights bookstore.” She outlined the biography she hoped to write:

“Shig was born in Seattle in 1926. His father, who came from a Samurai family ran a butcher shop called Annex Meats, “Following the implementation of Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, the Murao family was incarcerated, first in Camp Harmony/Puyallup Assembly Center, then in Minidoka, Idaho, where Shig and his sister Shiz graduated from Hunt High School. Just shy of 18, Shig then trained and served as a Japanese language interpreter for the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Service in occupied Tokyo in late 1945, while his older brother Shigesato joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Following service in the MIS, Shig returned to the U.S., traveling through New York, Chicago, and Reno, before settling down in San Francisco, where he would hold court in the North Beach neighborhood for the rest of his life.”

In another piece on the Nikkei West site, Wakida states: ‘What’s ironic is with Chinatown and a burgeoning Filipino population flanking North Beach on one end and the jazz scene going full blast up and down Broadway, the forced removal of the JAs and the exotification of all things Japanese and Chinese by the Beats, it’s impossible not to look at the story from the race perspective and how it was absolute in its influence on the art, music and poetry of this particular scene… How ironic and sad that the white establishment had to write out such a critical part of the ‘Howl’ story — the very man who, a mere 10 years before, had been forced into an American concentration camp would be the one to take the fall for defending the right to freedom of speech and in the name of literature, only to be deliberately forgotten a generation later with the creation of this film.’”

Ferlinghetti’s Role Model

Ferlinghetti was obviously influenced by the French poet, Jacques Prévert. In 1964, as number nine in the distinctive series of “Pocket Poets” paperbacks, City Lights published half the poems in Prévert’s best-seller, Paroles. Ferlinghetti wrote in an introduction that he had translated them “for fun.” (French had been his first language.) He saw a political affinity between Prévert, a Communist, and the hipster/left of Allen Ginsberg and C. Wright Mills:

“Many other poems in Paroles grew out of World War II and the Occupation in France, and it is plain that Paroles means both Words and Passwords. Prévert spoke particularly to the French youth immediately after the war, especially to those who grew up during the Occupation and felt totally estranged from church and state. Since then we have had our own kind of resistance movement in our writers of dissent —dissent from the official world of the upper middleclass ideal and the White-Collar delusion and various other systemized tribal insanities. Prévert was saying it in the ’30s.”

Upon Looking Into Ferlinghetti

Reading Jonah Raskin’s