By Fred Gardner: Mischievous Hendrik Hertzberg emailed, “Have you seen my friend Clara Bingham’s oral history of 1969-70? Jane Fonda talks about you in it. Curious about your reaction.” It was too bad, he added, that Bingham hadn’t interviewed me. I replied that if sent a review copy, I’d write a piece called “Clara Didn’t Ask Me, But…” And so they sent the book, in which Jane Fonda mentions that when she returned to the US from Europe at the end of the ’60s, intent on learning more about the antiwar movement, I suggested that she visit one of the coffeehouses that drew hip GIs in towns near Army bases.

The night I met Jane Fonda I was in a daze of misery. There had been a preview of the movie Zabriskie Point at a screening room in LA. I was appalled at how bad it was. Going in I knew that all the lines I’d written had been vetoed by the young stars, but I hoped the director, Michelangelo Antonioni, had miraculously made a meaningful film. No such luck. My name was on it (with four other writers), but I hadn’t gotten a word in edgewise and I thought it was an embarrassment. I felt used. They’d wanted my connection to the movement not my input as a writer. The screening ended, people were shaking hands with Antonioni like on a reception line, I’m right behind Marlon Brando who pronounces solemnly, “Very great. Very powerful.” Then it’s my turn and I say, “Something went very, very wrong. Is it possible to use other footage and recut it?” Mike Nichols pulls me away by the arm and intones with extreme seriousness and suppressed outrage, “You cannot talk like that to a man about his work!”

Then there was a dinner party at the house Nichols was renting. I did not find the witty talk entertaining and was hanging out in the kitchen with a cook named Robert when Jane Fonda found me and we had the conversation that she refers to, partly, in Clara Bingham’s book,”Witness to the Revolution.” Or maybe Jane recalled more and Clara didn’t use it. What I’d told her in the kitchen all those years ago was that friends and I had set up some Frisco-style coffeehouses near Army bases, but I had distanced from them and didn’t know why. I hated the war, of course, but I didn’t like the way the Peace Movement leaders were operating. I tried to explain my confusion to Jane and Robert in the kitchen. She heard the part that she wanted and went off on her trip.

I moved back to New York in the spring of 1970 and applied to medical school. Jane was there making the movie “Klute” and we became friends. Next she was going to appear in an antiwar cabaret show that would play Fort Bragg, San Diego, and other military towns. Her ability to draw the media had given her tremendous clout in the movement. I figured with Jane as my ally, maybe I could convince the organizers running the GI coffeehouses to cut down on the proselytizing. So I signed on as stage manager of the “FTA” show and wrote a song that Jane sang verses of during the black-outs between scenes. Politically, my influence was nil and after the San Diego performance I dropped out and started railing against “the classy left.”

“Witness to the Revolution”consists of interspersed recollections of the (academic) year 1969-70 by about 100 people. Bingham describes her sources as “radicals, resisters, vets, hippies.” I had crossed paths with some of them way back when and it seems like the show-offs are still showing off (like Peter Coyote) and the sensible ones are still sensible (like Julius Lester). The interview excerpts are well integrated in chapters headed The Draft, Psychedelic Revolution, Madison, Radicals, Resisters, Woodstock, Weathermen, The Chicago Eight, Ellsberg, Moratorium, Silent Majority, My Lai, Exile, December, War Crimes, Townhouse, Women’s Liberation, Cambodia, Kent State, Strike, Underground, Culture Wars, Coming Home, Army Math, Escape, and Reckoning.

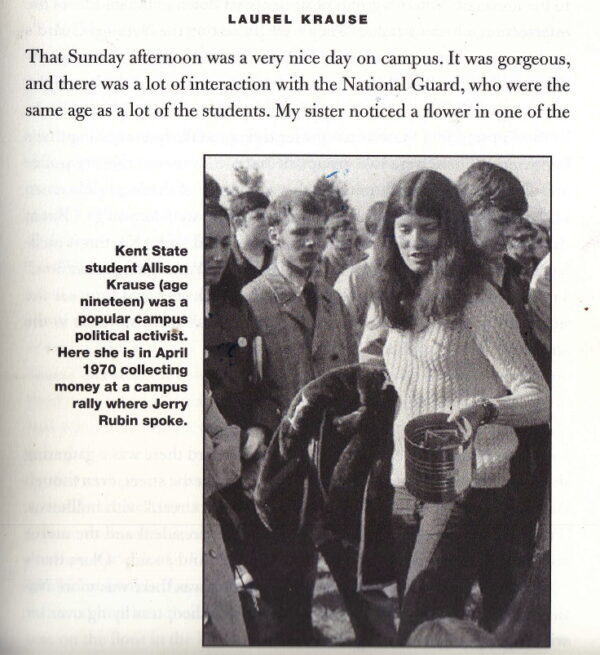

The chapter on the My Lai massacre features the great journalist Seymour Hersh telling how he got the story, and brings it all back home. The Kent State chapter includes comments by AVA contributor Laurel Krause, whose sister Allison was one of four students murdered by the Ohio National Guard (on orders, ultimately, from Governor John Rhodes). There is a photo of beautiful Allison Krause —”a popular campus political activist,” says the caption. “Here she is in April 1970 collecting money at a campus rally where Jerry Rubin spoke.” I can just imagine that little narcissist urging the Kent State students on, “We owe it to the Vietnamese people…” To what extent should Jerry Rubin —and whatever “mobilization” group sent him to Kent State— be held responsible for the antiwar students’ mood and tactics on May 4?

From “Winess to the Revolution.”

Laurel Krause: The Guard all turned in unison, and they all shoot in unison. Sixty-one to 67 bullets at unarmed students. My sister was 343 feet away from her shooters. Everyone that was killed was at least a football field away. These excuse that the Guard gave was that the students were attacking them, they feared for their lives, and had to respond to sniper fire in the crowd. The part that you don’t hear is that my sister bled to death, for 45 minutes, before an ambulance came, yet ambulances were available over the hill, reserved for guard and authority injuries only…

Lying near Allison (and Jeffrey Miller and Sandy Scheuer, who also were killed) was another student, Dean Kahler. He told Bingham:

I started following along behind the Guard when they formed up their line and started marching uphill and I thought, Oh, they’re just going to go to the top of the hill to shoot tear gas. I’ll just follow along… I was on the practice football field when they turned and lowered their weapons. I thought Oh my God, they’re going to shoot. Because I’m a farm boy and I’ve carried a rifle and a shotgun, and when somebody makes a deliberate motion like that, and lower their weapons, pointing directly at you, that’s a sign that they’re ready to shoot because I’ve done that many a time when I’d been rabbit hunting or pheasant hunting as a kid, and it was very frightening. I looked around, and there was no place to hide. I jumped to the ground, and I could hear bullets hitting the ground around me. Why are they shooting and me? And then I thought, Oh my God, I hope I don’t get hit. And then, at about that time, I got hit, and it felt like a bee sting…

I couldn’t get up and I was lying there and people were gathering around me, and I asked, believe it or not, “Is there anybody her who’s got their first aid merit badge in Boy Scouts?” Yeah, four five guys raised their hand. I say, “I need six people. I’m not going to die, right here, with my face in the grass. I want to be turned over.” You know, there is a way to do it. They do it today, and EMS does the exact same technique that I learned in Boy Scouts when I was in high school.

No Guardsmen came to me at all. Actually, one of the black students came over to me. They told the black students to stay away from these big gatherings, because they knew what had happened in 1967 and ‘688 in Ohio, in Youngstown, in Cleveland, Toledo, and the Columbus area. So, they told them not to be where lots of white people were gathered. They might get targeted. But the leadership was there that day, and one of the guys came to me and said “Who are you? do you know your parents’ phone numbers?” Within five minutes of the shootings, he was on a phone calling my parents and letting them know about it, almost instantaneously. Unlike Joe Lewis’s parents, who found out about it through the news. Same with Jeffrey Miller’s mom.

Laurel Krause recounts how her family was notified:

My uncle Jack in Cleveland heard my sister had been killed on the radio, and he called my dad… My mom worked. I called her. She got in the car and came home. She called and called band called, finally got through to Robinson Memorial Hospital, and someone told her that Allison Krause was dead on arrival. My mom collapsed and I screamed. Then we drove to Robinson Memorial to identify her body, and men with guns standing outside the hospital muttered, ‘They should have shot more.”

Dean Kahler was put into an induced coma and operated on. He told Bingham:

Fortunately, the only organs that were damaged were the lungs, the diaphragm, and the spinal cord… When I came to, the doctors says, “You know what’s going on?” I said, “Yeah, I’m probably not going to walk for the rest of my life.” He goes, “I think you’re right. Why are you so cavalier about it?” I said, “Well, thank God. I’m just happy to be alive. I’m opening my eyes, I’m in a lot of pain, but I can talk, and I can breathe, and what you told me is I could live a very full life for the rest of my life.” He says, “Yes, you can, and yes, you will.” So that’s where I come from. I’m only a paraplegic. I’m not a quadriplegic.”

I’m an old man but if Jerry Rubin in his prime was put in front of me, I think I could strangle him with my bare hands.

Clara Didn’t Ask Me, But…

Bingham was at Books, Inc. in Berkeley the other night and I went to hear her with my old friend Larry Bensky. “It’s a good crowd,” he said as we arrived—about 70 people. The average age was about 70, t0o (in a college town).

Bingham said 1969-70 was “the crescendo of the ’60s.” I thought the worldwide finale had come in 1968, and 1969-’70 was the disturbing coda. And I think her title, “Witness to the Revolution,” is misleading, to put it diplomatically. There was no revolution, the ruling class stayed in power. And the subtitle referring to “the Year America Lost Its Mind and Found its Soul” is meaningless.

I haven’t finished the book yet. I put it down and added a new verse to an old song:

They call it the city of angels, lady, that don’t mean that everybody who lives there is. Lots of money changing hands on the corner of Politics and Show Biz. Jane, stalkin’ my mind from time to time. Can’t escape no how. Great Fame can mean this is then and that was now.

Once you slandered me, well I understand it was for the candidate. Playing Miss Hellman as Muriel Gardner, how can I relate? Jane, stalkin’ my mind from time to time. Seventy-six. Sixty-nine. Never for a minute following my line

Down Jane Street, Old Jane Street, Walkin’ down Jane Street on a screen.

Married to a billionaire and shilling for videos on fitness. A-hooing with “Chief Nakahoma,” so embarassing to witness. Jane, stalkin’ my mind from time to time. Out West. Back East. Of all of your directors I directed you the least.

Seen you in the supermarket, you and Lily Tomlin got a big hit. Leanin’ in for Hillary, I ain’t surprised one little bit. Jane, stalkin’ my mind from time to time. Talkin’ to Ms Bingham, there you are again. Great Fame can mean that was now and this is then.

Outro

I woulda told Ms Bingham how long ago I couldn’t get through to you or Michaelangelo.