Members of the Society of Cannabis Clinicians working on new CME modules might want to climb this thing… I boldfaced a sentence in which the word behavioral is used misleadingly; the right word would have been political. This is not nit-picking by an old-school editor. “Behavioral” has a blame-the-patient overtone and points away from the causal factors. —FG

Viewpoint: Ascent to the Summit of the CME Pyramid

By Robin Stevenson, MD1; Donald E. Moore Jr, PhD2

JAMA. Published online January 22, 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.19791

Medical education is a continuum of 3 parts; undergraduate medical school education, postgraduate training, and continuing medical education (CME). CME differs from the other 2 educational components in that it has generally not been based on an explicit curriculum. Recently, CME has increasingly focused on addressing professional practice gaps, defined as the difference between what clinicians are currently doing and what they should or could be doing.

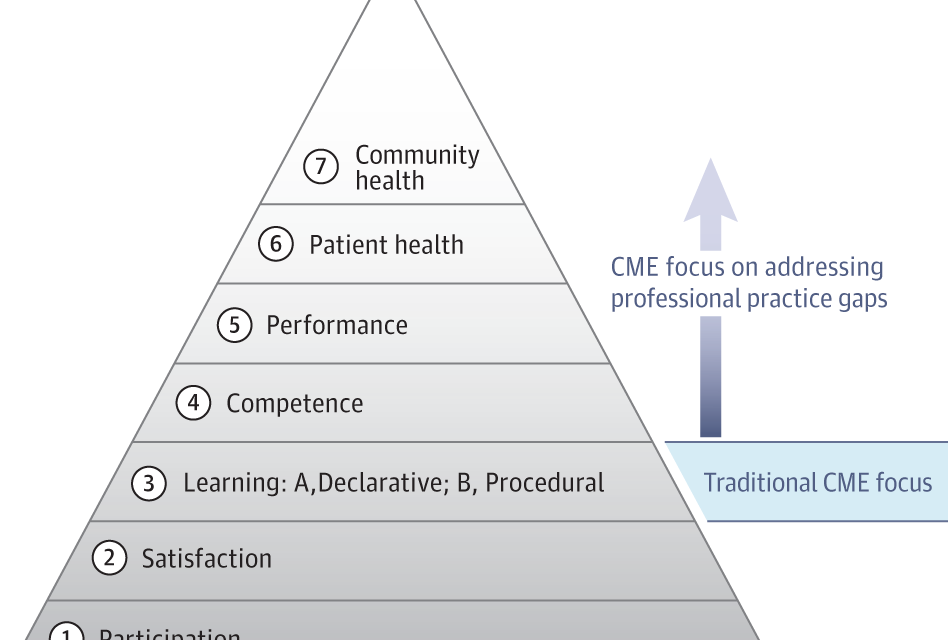

An outcomes framework has been proposed for CME, in the form of a pyramid (Figure) that provides a perspective on how the increased emphasis on addressing professional practice gaps might be accomplished.1 The pyramid is based on 7 levels of outcomes that are associated with the decisions of a clinician to participate in learning, to engage in learning, to use what he or she learned, and, at the summit, the effects of learning on patients and community. CME has traditionally been focused on learning (level 3) and in some cases on competence (level 4), which is similar to the “shows how” level of the pyramid in which a learner demonstrates to a teacher that he or she can do what has been learned.2

CME indicates continuing medical education.

A synthesis of systematic reviews of effective CME has shown that CME activities that are more likely to lead to improved clinical competence (level 4) and performance (level 5) result in better patient health (level 6).3 This type of CME activity has 5 characteristics: (1) active learning techniques; (2) multiple exposures to content; (3) a variety of instructional strategies; (4) more time for deeper penetration into what is being learned; and (5) a focus on outcomes important to physicians.

These developments suggest that over the past decade, CME may have ascended the pyramid to performance (level 5) and patient health (level 6). This prompts 2 questions. First, can CME be viewed as an important strategy to address suboptimal care? Second, can CME, as a result of focusing on performance gaps, be expected to affect community health (level 7) at the summit of the pyramid, if it continues to move in this direction?

Outcomes up to level 6 in the pyramid are based on meeting learning needs that practicing physicians may recognize in day-to-day professional life. Such needs may be confirmed by opinions from interprofessional teams, audit procedures, peer group discussions, and hospital or practice management groups. Gaps are identified, and analysis of their causes often shows that those gaps are attributable to barriers transferring competence to practice-based performance, less commonly to incompetence, and least of all to lack of knowledge.

It could be argued that if CME contributes to improving patient health on a broad front, such that many patients and many diseases are affected, then community health, that is, population health, must necessarily improve. But community health might still be suboptimal if the health care system is poorly funded, poorly designed, poorly managed, and wasteful of resources. Community health is also impaired if there are cultural forces acting against the interests of members of a community, cultural forces causing them to behave in ways inimical to their health, or if they do not take personal responsibility for their health. For example, the growing income-related gap in life expectancy for both men and women in the United States is predominantly behavioral rather than medical.4

The increasing focus on clinician and team performance in accreditation requirements such as the American Board of Medical Specialties Programs for Maintenance of Certification, part IV: Improvement in Medical Practice, addresses practice gaps at the lower levels of outcomes, which are usually apparent to physicians. But the identification and analysis of professional practice gaps at the higher levels of community or population health present challenges to CME providers, who must actively become organized to discover practice gaps. The use of big data may create opportunities for understanding the gaps in population health. For example, gaps in population health can be identified with big data accessed from the Bronx Regional Health Information organization with data on more than 2 million persons, NHS Digital in the United Kingdom, and the national electronic health record systems in France and Germany. The various agencies that contribute to gap analysis for lower-level outcomes may not be suitable for examination of gaps in community health because of limited perspectives. This would require government agencies, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Royal Colleges in the United Kingdom and Canada, specialist medical societies, and CME providers at national and state levels, who could then determine the appropriate educational interventions to address gaps in population health in specific regions.

However, the CME delivered by many of these organizations, particularly those in Europe, does not reflect recent advances in educational sciences, is primarily didactic, and outcomes are seldom evaluated. If the organizations could be persuaded to accept the challenge to ascend the pyramid to the summit, they would have to change their approach to providing CME. They would need to accept that the necessary precondition of CME is identifying practice gaps and that CME is an important tool by which those gaps can be addressed. For example, respiratory and oncology societies could audit lung cancer survival across the United States or Europe. If practice gaps were found in some areas and the causes identified, customized CME programs in conjunction with community education could be devised and directed at the underperforming services.

Some practice gaps are caused when medical care and social care are influenced by cultural factors, as in the long-term care of patients with dementia in nursing homes. Geriatric and palliative care societies, medical ethicists, and even philosophers could address this difficult problem and seek consensus approaches that could be implemented through the agency of a CME program directed at medical and nursing professionals and also at the general public. Oncology and intensive care societies could consider a possible practice gap in end-of-life care, in terms of the cost both to the taxpayer and to the dignity of patients.

Arguably the most important practice gaps are those that are evident from comparative analyses of the quality of medical care in different countries. In the recently published Healthcare Access and Quality Index,5 the United States occupied the 35th place among 192 countries, and the United Kingdom was in 30th place. The 2016 Euro Health Consumer Index report compared health care in 35 European countries, with the Netherlands at the top and Romania at the bottom.6 The CME community is entitled to conclude that many countries have gaps in the organization of their health care systems and that these gaps affect community health and therefore are a proper area of concern for organizations that provide CME. These gaps may relate to differing perspectives on health policy, for which the primary concern is not always the interests of patients, and also may result in fragmented health care delivery. In these areas, national medical organizations should engage in gap analysis with departments of health, health economists, and the general public.

Physicians who accept these challenges exceed the requirements of traditional CME and when addressing patient and community health can reasonably consider themselves as engaging in Continuing Professional Development (CPD). A recent definition of CPD underlines this point: “CPD calls for clinicians to engage in a process of monitoring and reflecting on professional performance, identifying opportunities to improve professional practice gaps, engaging in both formal and informal learning activities, and making changes in practice to reduce or eliminate gaps in performance.”7

Improvement in community health by addressing practice gaps will not be achieved by CME professionals alone, but will require involvement of many organizations, including specialist medical societies and boards, academic medical centers, and government agencies. Their perspectives include learning health systems, implementation science, quality improvement, informatics, decision support, and maintenance of certification. For example, this year the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is proposing completion of an accredited CME program directed at performance or quality improvement. This Clinical Practice Improvement Activity must address a quality or safety gap that is supported by a needs assessment. The proposal has been endorsed by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, which is now collaborating with the American Board of Medical Specialties to facilitate the integration of CME and maintenance of certification.

Each one of these well-meaning groups has a certain perspective, but it may not be comprehensive enough to have an effect on suboptimal care and professional practice gaps. Currently their activities are fragmented and efforts should be undertaken to avoid overlap and, in the future, to coordinate strategies to prioritize and address gaps in community or population health. This should include research activity to generate an evidence base to bear on policy decisions. Such developments could advance the ascent to the summit of the CME pyramid.

Corresponding Author: Robin Stevenson, MD, University of Manchester Innovation Centre, Arch 29 North Campus Incubator, Sackville Street, Manchester M60 1QD, United Kingdom (rstevenson@jecme.eu).

Published Online: January 22, 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.19791

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Additional Contributions: We thank Lewis A. Miller, MS, CCHP (WentzMiller Global Services), for reading and commenting on the manuscript. Mr Miller received no compensation for his contributions.

References

1.

Moore DE Jr, Green JS, Gallis HA. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29(1):1-15.PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

2.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9)(suppl):S63-S67.PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

3.

Cervero RM, Gaines JK. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(2):131-138.PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

4.

Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750-1766.PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

5.

GBD 2015 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators. Healthcare Access and Quality Index based on mortality from causes amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a novel analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):231-266.PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref

6.

Health Consumer Powerhouse. Euro Health Consumer Index 2016 report. https://www.healthpowerhouse.com/files/EHCI_2016/EHCI_2016_report.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2017.

7.

Campbell C, Silver I, Sherbino J, Cate OT, Holmboe ES. Competency-based continuing professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):657-662.PubMedGoogle ScholarCrossref