By Fred Gardner —From the Anderson Valley Advertiser September, 1994.

The Straus Family Creamery started selling organic milk in glass bottles on February 7 of this year. The FDA had approved recombinant bovine growth hormone for use a few days earlier –which is the main reason Rosie decided to spend $1.25 for a quart of Straus Family as soon as our local market began carrying it. She also liked the look of the bottle, for which you leave a $1 deposit.

We never went back to Lucerne. Straus Family whole milk is sweet, rich and delicious. Even their non-fat milk is tasty, I swear.

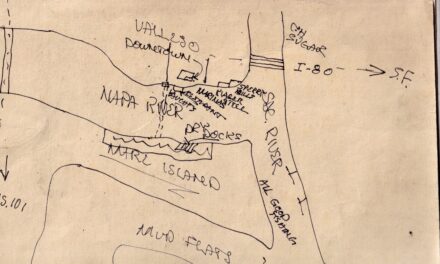

The creamery —which Albert Straus and Michael Wiener designed and equipped— is in a large steel building a few miles from the Straus’s 660-acre dairy in western Marin County, near the town of Marshall. Sales are not yet at the point where milk is being bottled five days a week. Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, half the milk produced by the dairy’s 220-cow herd gets processed at the creamery; the other half is shipped to a co-op. On Wednesdays the 8-person workforce produces butter and does general maintenance. Four more people work full-time at the dairy.

Rosie and I interviewed Albert Straus, who is 39, and his brother Michael, who is 27, at the creamery office on a recent Friday afternoon. People were leaving work, saying goodbyes for the week-end.

How do you make the great milk?

MS: Happy cows. AS: We started about four years ago transitioning our land and the cows to organic. Developing sources of organic feed. Figuring out how to work with alternative remedies.

You were running a conventional dairy till then?

AS: Oh yeah. My father started in 1941. I’ve been in partnership with him since ’77. We were a conventional farm selling through cooperatives, trying to survive at market rates that have been flat for 20 years. I had a couple of motivations for doing this. One was to survive. The other was to go more directly to market and make the products I really want to make.

What was involved in going organic? What are the costs?

AS: We hadn’t used any herbicides in 20 years, so that was relatively simple. We stopped using commercial fertilizers on the pastures where cows grazed –we had only used a very limited amount the past five years on fields that we couldn’t get to with manure. We didn’t use any antibiotics after June of ’92. It took me about a year to learn what homeopathy is all about. There are only two veterinarians in the nation using that approach for cows. Now I kind of have my veterinarian trained to not use antibiotics and hormones when something comes up. We don’t use pesticides. There was a one-year transition in which the crop that we grew for the cows, which is oat silage, became all organic [silage is a way of preserving feed involving fermentation]. For 10 months we had the cows on 80% organic feed, and for two months at 100%. We finished that transition year in December [’93]. We had organic feeds that weren’t as high quality as conventional, so we lost 10 to 12 percent production, which cut into our income. Plus it costs us anywhere from 25 to 100 percent more than conventional feed.

Where do you buy organic feed?

AS: Most of the alfalfa comes from California and the grains come mainly from the midwest. I’m trying to develop more local sources.

Why isn’t the organic feed as high quality as conventional? What’s it lacking?

AS: Alfalfa is kind of a rotation crop for most organic farmers –a sideline. Many go for quantity instead of quality by letting it grow longer. Our cows were the top producing cows in the North Bay in 1991, and now we’re almost average.

It’s like you’re going against a fundamental economic principal: letting production go down.

AS: Well, there’s give and take. What I’m trying to do is be able to set my own price for my own product, which farmers never have been able to do. The government has a pricing system that essentially has gone down and down and down, creating “market” prices that no one can survive at. The minimum is the maximum. We have no control over it. The cooperative system doesn’t help. Getting directly to market is something I’ve been planning to do for a long time. I went to Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo and took ice cream making and butter making and other relevant courses. My senior thesis in ’77 was on setting up a processing plant. We put together a whole business plan as to what it would take. Originally we were going to set the plant up at the dairy. We were able to cut our initial investment by renting this building [six miles from the dairy]. Then we set out to get financing and test the market.

Were your parents involved in developing the plan?

AS: They’re totally involved in the whole thing. We work jointly. We talk over things and try to make the best decisions for all of us. I worked with a friend in Petaluma and another engineer friend who helped develop this whole plan. There’s hardly any information on what it takes to set up a milk processing plant, what it costs to run a milk processing plant. We kind of had to pick it up anywhere we could: Pennsylvania, the state of California. And all the figures are meant for huge, huge plants.

What’s the connection between having your own plant and having an organic product?

AS: We have developed our own way of washing and sanitizing our equipment that meets both the orgnic laws and the dairy laws. And the state dairy inspectors have worked with us. We’re using hydrogen peroxide as a santizer. It breaks down in water—it’s not like iodine or chlorine, which leave residues. The organic laws weren’t really well developed because they state that after you clean you can double rinse with water, or you can steam. But under the dairy laws, once you clean a system you can’t inject anything else into it, including water, which is not a sanitizer. And so I had to work on that… We don’t do anything to the milk. We don’t add anything, we don’t fortify it. The whole milk, we just pasteurize it. We heat it up to 164 degrees for 20 seconds, and then back down to 35 or 40. The nonfat, we separate all the cream out and either package it as whipping cream or make butter out of it. [The same bottles are used for all four products. The whole milk gets a red cap, the nonfat a blue cap, the whipping cream a green cap and the buttermilk a yellow cap.] The buttermilk, no one really knows what it is, because it’s real buttermilk, directly off the churn, uncultured and sweet.

How come just whole milk and non-fat? Why no low-fat?

AS: They have a law in California that if you make low or extra-light milk you have to add solids–nonfat powdered milk or condensed milk– to increase the solids level to 10 percent. We can’t do that because there’s not enough organic powdered milk in this country –no one’s producing it other than CROPP in Wisconsin. [The Coulee Regional Organic Producers Pool.]

When did you hit the market and what was that business about the government telling you you couldn’t say “no bovine growth hormone” on your label? [The Strauses use a small sleeve slipped over the neck of each bottle for labeling purposes.]

AS: We came on the market February 7, three days after bovine growth hormone was approved by the FDA. And since there’s a state law against an organic producer using any hormones or antibiotics, and we’re the only organic producer, we figured we should say something about it. [The Strauses included a sentence on their original labels stating that their milk didn’t contain BGH.] But then the language wasn’t quite right and we had to say ecombinant END bovine growth hormone –because there are natural ones– and the FDA wanted us to include a whole paragraph saying it wasn’t necessarily bad for your health and that no significiant differences had been found. So we ended up putting a little strip of paper over the original statement to satisfy everybody. Now they’ve stated that we, as the only organic dairy in California, can legally say that we don’t use recombinant bovine growth hormone.

MS: Meanwhile Berkeley Farms and Clover Stornetta are making advertising claims that their milk is rBGH free. And Trader Joe’s posts a notice on their dairy cases that their milk and milk products “come from cows which are not treated with” bovine growth hormone. They might have producers that give fluid milk to them that’s free of BGH.But it is currently impossible to track milk from rBGH-treated cows, and therefore entirely misleading for conventional dairies to make such claims.

How are sales going? Are you meeting your goals?

MS: We’re meeting our goals but it’s essential that we keep going. We’re only selling about half our milk direct to market. The other half goes to the co-op [the California Cooperative Creamery] . They’re buying it as surplus milk and paying us a very low price for it. And then they charge us a high price on top of that for hauling it.

What’s the government role in setting the price of milk?

AS: Essentially, we’re not getting any government subsidies. They said ‘We’ll buy cheese and butter’ [at a certain price, regardless of the market price]. But the support price for butter has gone from $1.50 per pound to 65 cents in the last decade. So if that’s supporting us, they’re supporting us right out of business.

The consumer is not paying what the true cost of the food is in this country. There were thousands more dairies in California not so long ago; now there are only two thousand. What’s happening is a system that forces farms to get bigger and bigger to try to survive, and food is in the control of fewer and fewer people. What I’m trying to do is say “This is what it costs me to produce it and I’d like to survive, and in return I hope to give the best quality product I can produce.” And I’m putting it in a reusable container, which I’m finding more and more is a very difficult thing to do, because this whole society is used to throwing things away and not dealing with bringing things back. It’s an uphill fight. The state has a law to recycle 50 percent of the waste by the year 2000. But they have no help to offer when it comes to reuse.

MS; The chains will not take our milk because it’s in bottles. It’s an uphill battle to get into United, Cala, Lucky’s, Safeway, for different reasons, but the main one is,

they want to get it in plastic or wax paper containers. We know that disposable containers are easier to handle, but we think plastic and waxed paper cartons are an unnecessary waste of resources. Besides, milk tastes better in glass.

How’d you get into the Fort Bragg Safeway? Does the manager of the dairy department have the right to place an order direct?

Some Safeways order centrally; others give the manager the right to purchase directly from manufacturers —as in Fort Bragg, Corte Madera and the Marina Safeway in San Francisco.

What’s the story on Castle Creamery? They sell milk in bottles.

MS: They just bottle it. They buy their milk from the co-op. Some of their products are good, but not organic.

What about Alta-Dena? Aren’t they organic?

AS: They’ve never been organic. Their claim to fame is producing raw milk –which means not pasteurized. For years Alta-Dena was run by the Steuve family; now they’ve sold to a French company.

Getting back to distribution –it seems like you’re in a lot of places after six months on the market.

MS: From the beginning we’ve had tremendous support from the healthfood stores –they welcomed us with open arms– and from lots of family-run groceries and smaller grocery chains in the Bay Area, including Andronico’s and Petrini’s. We’re now in LA –our sister Vivien is helping us market there. We’re all over California and in five other states, through our distributor in LA who is also a national distributor and has had requests from all over the country.

How does it work? You truck to the various distributors?

MS: No, they come here and pick up the milk –we have six distributors. The two main ones in northern California are Rock Island and Dairy Delivery. One comes four days a week and one comes five days a week. The smaller ones are Wild Oak, West Marin Dairy. Albert’s Organics –they deliver to southern California. And we’ve now signed up with a person that does home deliveries throughout the Bay Area: “The Milkman,” Pat Borella. He’s based out of Santa Rosa.

Does he deliver to Boont Berry Market in Boonville?

Wild Oak distributes there.

When we get our Straus Family milk at the corner market at Third and Hugo, who brought it there?

MS: Probably Rock Island.

Would they also deliver to Andronico’s on Irving Street? Have they got things divvied up by geography or is it whoever got the account first?

MS: Rock Island delivers to Andronico’s. There’s overlap –with sort of a truce between the distributors not to go after each other’s accounts with Straus Family Creamery products. Rainbow, Real Foods, Inner Sunset –those are all Dairy Delivery.

What’s your total production?

AS: We’re selling about 4,500 gallons a week to market –and an equal amount to the co-op.

220 cows produce 9,000 gallons of milk a week? And you used to do better than that?

MS: They’re good cows. (Laughter in the room.)

AS: Young cows and older calves graze in the fields. Milking cows graze on a rotational basis, weather and soil conditions permitting. We work hard. We milk three times a day, which is less stressful than two times because the udders don’t get so full. The actual milking lasts approximately 5 to 7 minutes per cow. Our cows produce approximately 8 gallons of milk a day.

Who works at Straus Family Creamery?

MS: You want to see our management scheme? (more laughter) It’s still in development. “Business first, management later.” There’s Bill and Ellen Straus,our parents. Dad bought the farm in ’41, then he got the neighboring ranch in the ’50s.

Was he a dairyman before?

MS: That’s a really long story –a long family history. [Maybe next week.] Our sister Vivien in L.A., who is an excellent actress, is now doing all the marketing in southern California and out of state. Michael Wiener is…

MW: Maintenance manager.

MS: Michael and Albert built this place up from scratch. They took a building that had been abandoned for God knows how many years –trashed– and made it into a working creamery –by working seven days a week for two and a half months. There’s our number-one pasteurizer, Paul –you need a license to pasteurize. [Michael Wiener also has a pasteurization license.] We get inspected a couple of times a month. Patti Hale is our office manager. There’s Jose Luis Alfaro, Jorge Alvarez, and Edie Sarton –production. Dan is our resident fix-it guy. He’s a mobile mechanic who’s helped us get a lot of this equipment working –this equipment that had been sitting outside rusting for so long.

Who handles the clerical work, Patti Hale?

MS: Most of it. She does the books. I handle some of our dealings with distributors. And there’s Sue Connely, who used to be one of the partners at Betty’s Diner in Berkeley –she’s our marketing consultant. Jeanne [Albert’s wife] and out mom both help out with marketing, in-store tastings, etc.

Is your goal to sell 100 percent of your product directly to market –meaning through distributors.

MS: Yes. And ideally we’d like to sell everything right here in northern California, in glass bottles as a local product. It’s meant for home delivery. We don’t need to be in 7 states. We shouldn’t have to ship it as far as L.A.

Are there certain venues where you’ve really caught on?

MS: It varies with the store. We sell tons of milk in Laytonville and Redway.

They’re organic and they have the money!

MS: Marin County’s a good market for us. Berkeley, Walnut Creek. There’s no question that the Bay Area is a good market for our product. AS: And it’s interesting how much more awareness of what “organic” means there is in northern California. MS: Vivien does tastings at markets in L.A. where she gets dirty looks from people when they hear the word “organic.”

Tastings are a great idea. Your milk is to Berkeley Farms what Peet’s coffee is to Folger’s.

MS: That’s why we do the farmers markets. Most people seem to love the milk, and it sells itself.

But it’s understandable why the word “organic” evokes a negative reaction. A lot of classy people who can afford the higher prices at the healthfood stores, and who have the time to shop at such places –while working people have to rely on the neighborhood supermarket– come on as if they’re smarter and better and hipper because of their preference for organic food. As if anybody wants to ingest poisonous residues.

AS: People don’t even know where the food comes from anymore. They don’t know what it is, they don’t know where it comes from, they don’t know how to make it. I don’t think it’s healthy. Then you get horomones being approved –people don’t even know how to discuss it, much less what it means to them. They swing from one side to another: butter’s bad, margerine’s good. No, margerine’s bad, butter’s good. Farmers in this country are now less than two percent of the population. Around World War II they were 40 percent of the population.

And that’s the definition of progress we get taught in school. In the old days everybody had to grow their own food. Now we’re all free of that terrible burden and can work in office buildings.

AS: There’s no farmer that makes it. Almost all the farmers have side incomes. I”ve got two businesses: the farm and the creamery. We’ve had to borrow from friends and family in order to do this. And we sold the development rights for our land to the Marin Agricultural Land Trust –the first agricultural land trust in the nation– which my mother helped start.

What do you mean when you say that people aren’t paying the real price of the food?

AS: If you look at the United States, food is cheaper than anywhere in the world. The quality may keep going down, but it’s cheap –and even cheaper on the east coast.

Are there other dairies watching your experiment and thinking about taking the same approach?

AS: There are other dairies interested in doing organic programs. There’s organic milk coming out of Wisconsin. They’re starting an organic dairy in Idaho. There might be one in Washington state. The one in Wisconsin actually started with 10 little dairies, now there are 55 dairies. I was just in Wisconsin for a few days looking at a butter printer [a machine that molds butter into quarter-pound cubes]… Our hope is that we’ll be successful enough in this venture that we could offer a model to other dairies, especially in this area.

What kind of cows do you have?

AS: We used to be all Jerseys and then in the ’60s we were forced to go to Holsteins by the milk plant to whom we were selling our milk because of the cholesterol scare. We’re now cross-breeding again with Jerseys, who give a higher percentage of butterfat and protein.

Any plans to expand the product line?

MS: Butter is next on the list –in normal packages, four cubes to the box, at all the stores. Organic chocolate milk. And we’re going to package in half-gallon glass bottles [in addition to quarts]. But you know, it’s a real struggle. One of our distributors has been frustrated because it’s so difficult to get our milk into the larger grocery chains in our glass bottles.

Why? What are they afraid of?

It’s more work. It’s more expensive for them to handle it –it might give them a higher insurance cost if someone drops a bottle.

But they carry a lot of products in glass bottles. Maybe they figure a milk spill takes longer to clean up than a broken jar of salsa.

MS: I think there’s just some sort of basic resistance. Maybe it gets magnified in the big chains. But we’re making inroads. It’s a long, slow, hard process. And we’re doing two things at once, selling organic milk in glass bottles. We’ve had comments that if we went into one-way containers –plastic or cardboard– that we’d be able to sell everything. But we don’t want to sell in plastic. We believe in reusable glass, which is why we’re sticking with it.

AS: It’s actually more economical, also. Recycling costs money. You’re taking it to somebody who’s going to sell it to someone else who’s going to melt it down and make it into another product. We’re buying glass bottles, made of recycled glass, and we’re reusing them, which is a lot cheaper for everybody involved. Just keep it out of the sunlight and keep it cold.

How much recombinant growth hormone is in the pipeline, as they say?

MS: Monsanto sent a letter out to dairy producers saying that there are now more than ten thousand dairies in the country using rGBH. They won’t reveal the names of the dairies, however.

Why have 10,000 American dairies started using it?

AS: They’re trying to survive. They’re in a bind. If prices were great, why would anybody want to do anything like that to their cows?

Is the fear that cows producing that much more milk will have more wear on the udders –meaning more mastitis and more antibiotics?

AS: Well, you’re making the cow produce more milk. The cow’s under more stress. You have to feed it more, you have to take care of it as well as you can. But under stress you get more diseases, naturally. You’ll have mastitis. There will probably be more digestive-type diseases. And they might not breed back [get pregnant], so you might be selling more cows. Theoretically, if you’re very good, you can try to prevent diseases as much as possible.

Even conventional dairies using antibiotics must withhold milk from sale til the milk tests negative [for antibiotics]. Some customers are concerned about reduced resistance to diseases which might result from the use of antibiotics in the food chain. That’s one of the reasons we don’t use antibiotics in our milking herd, to give consumers a choice.

What’s the productive cycle of a cow?

AS: It’s 10 to 11 months milking, two months before they have the next calf, then they start production again.

Increasing milk production is in whose interests?

AS: It’s not in the interests of the producers. There’s too much milk in this country already. The price has been depressed for 20 years. To produce more milk is only going to depress it even further. Maybe it will be a short-term gain for farmers who need to get the extra income that 10 percent more production would bring. But in the long term it will depress the prices even further and put more of a stress on those same dairies that are trying to survive.

Whose interest is it in to keep milk prices depressed?

Actually, everybody but the farmers.

The terrible truth is out.

AS: We struggled for years to get our co-op to raise prices. We’d say “You control most of the milk in the state, why can’t you get your customers to raise prices?” They wouldn’t do it. They sai d “You can’t do that.” We said, “Why aren’t you bringing a higher price to the dairyman instead of making a higher profit for your co-op that trickles down a little bit to the dairyman?”

MS: The biotech industry stands to gain from rBGH. And Monsanto expects to break even on it this year.

I can’t get over the fact that the organic food decreased your productivity.

AS: We had a hard time finding enough of the types of feed we needed –we couldn’t get enough roughage. Eventually we made a balanced ration but the alfalfa hay that we bought was of a lower quality and secondly, we used to use sugar beet pulp for a concentrated fiber source, but there are no organic sugar beets in this country that we know of. We finally found almond hulls which had enough of the stuff that we needed to up the amount of fat in them.

Do you devise the diet for the cows?

AS: I source everything. I work with the feed broker I used to work with conventionally. He can get railroad cars together and trucking together and give me contacts as to the farmers that grow organically and the brokers in the midwest.

MS: Albert had to build his own mill at the dairy to grind all the grain. There were no organic feed mills.

AS: For years I’ve been buying commodities and mixing my own feeds. To do this I need to bring whole grains in from farms in Montana, the midwest, wherever I can find them, and mix them into useful form… No one has produced organic feed because there was no demand for it. Now they don’t quite believe it when I say, “I need it now,” and “I”m willing to pay your price for it.” Still some of these farmers say “Oh, I didn’t get a chance to put it in this year.” They let time go by and then it’s too late to put the crop in. I’m just finding some alfalfa crops in California that might meet my needs. It’s not going to take that much, I just have to find the right quality. To make hay, your timing has to be right. You have to water it right, you have to feritlize it right.

At what age did you formulate this dream. Did you know all along that you were going to follow your father in the dairy business?

AS: At one time I was thinking about becoming an engineer; that was before I went to college. But I didn’t like being inside. (Laughs, blushes.) So I went to Cal Poly in dairy and ended up taking quite a few manufacturing courses. Actually, I’ve had my professor from Cal Poly come up here who taught ice-cream making, butter making and condensed milk-making lab. I’m the first student he’s had in 30 years who actually started a creamery. So he’s very excited.

What do people do with degrees in dairy?

Most people go to work for someone else. They go to a Safeway plant, or Berkeley Farms. They might go into management.

As we were getting ready to go downstairs to examine the equipment, we asked about the mansion we had seen looming on a knoll above the creamery.

MS: This whole ranch used to belong to Synanon. This steel beam that runs across the middle of our office we assume is the beam that Chuck Dederich [the founder] hit his head on.

I don’t know Synanon lore. What happened?

Chuck Dederich hit his head on a beam and that’s when they all shaved their heads.

What?

The story is, he hit his head on this beam while the building was under construction, got really mad and said “Whoever was the fool who did this is going to be made an example of and have his head shaved so that everyone knows who it is.” It turned out to be his son. Then, for some reason, everyone shaved their heads.

On The Line

Paul the pasteurizer is leaving as Michael Straus leads us downstairs from the office and we commence our tour of the creamery –a 12,000 square-foot steel building with a concrete floor and a few partitioned rooms. The ranch on which the building is located was owned by Synanon until the mid-1980s. Once upon a time it was the Magetti ranch. Michael’s brother Albert, who is 39, recalls trick-or-treating here. One of the Magettis was his teacher at the elementary school in Marshall.

When the Strauses leased the building, Michael says, “This place was just a huge empty warehouse. Nothing. Everything was broken. Power was iffy.” Albert bought used (but not cheap) processing equipment from creameries all around the country, which he then adapted and installed with help from friends. Michael says, “This whole project has brought together so many people who believe in what we’re doing and have helped out in so many tremendous ways –their time and energy and ideas and their love. It’s been a coalition-building project.”

Tanker trucks bring milk from the dairy and distributors bring returned bottles in cases. Bottles are unloaded from cases and cases are washed in a special washer. The bottle washer looks like R. Crumb drew it. In fact it was acquired from the Kesey family dairy in Oregon (producers of Nancy’s yogurt). Bottles go through three baths: a caustic, a rinse and a sanitizer. Hydrogen peroxide is used as a sanitizer because it breaks down into water. Conventional sanitizers like chlorine and iodine, are not used because they leave residues. The bottle washer was originally designed to use more than nine gallons of water per minute. Albert and his friends redesigned it to use only one gallon per minute, and that water is redclaimed for other uses. Dan, the can-do genius, figured out how to get the whole system working.

Held upright by railings, the bottles come down a narrow curving assembly line, the floor of which is made of steel slats. They push up against valves and the milk flows in. When full they come underneath a capping machine. Cap slides on top of bottle, gets crimped by crimper. Bottle continues down the line to dating machine, gets date stamped on top. Michael or another lithe youth takes bottles from assembly line and places them in cases, all in the right direction so they look nice. Put beautiful collars on by hand and roll them out to the floor, where they will later be picked up by… The bottling line gets slowed down when they’re bottling cream (which flows more slowly). The work involves a lot of bending and twisting.

Now we follow the course of the milk, which is trucked over from the dairy six miles away and gets pumped into a holding tank. From there it travels through stainless steel pipes to various stations. First it goes through a pasteurizer –a plate cooler with hot water and steam and cold water flowing through different sets of veins. By the time it comes out 20 seconds later it’s been pasteurized and cooled down.

There is a 4,000 gallon tank which enables them to bring the milk into the creamery the night before it’s bottled. (Originally they brought the milk in the morning and it took time to get rolling. Everything’s constantly being changed in the interest of practicality. Every minute counts in production.)

The separator operates by centrifugal force, separating out the cream and creating non-fat milk. The cream is put into containers and is then either bottled or made into butter. The rest of the milk goes into a tank and from there to the bottling equipment.

There is a back-up pasteurizer that was in use for their first month of production. It took four hours to process 400 gallons. The first day in production, back in February, the cycle lasted 36 hours because the equipment was so slow.

They have recently acquired a machine called “a bag-in-the-box filler.” (Remember wine in a box?). The plan is to sell milk in 5-gallon plastic bags to organic cheesemakers and to local restaurants and cafes who can’t handle dozens of bottles. The Strauses have plenty of milk they’re not selling to market at present –about 4,500 gallons a week. The bag-in-the- box machine just might be the answer. Dan should have it up and running by the time you read this.

The butter churn is a stainless steel cylinder, about 6-feet high and three-feet wide, mounted on a horizontal shaft. Cream is poured in, churned, and separated into butter and buttermilk. The buttermilk gets drained off and bottled. Butter is not generally made in churns anymore. A newer porcess, called “continuous churning” is more widely used because it can churn huge amounts of butter more quickly. The Strauses’ recently acquired butter printer will press it into quarter-pound cubes. Paper wrappers come off a spool and get cut and folded around the cubes. This machine was built in Germany, used in California, shipped to Wisconsin, and is back once more.

Michael says his brother Albert got involved in the dairy at a very early age, and has always been very innovative in his approach to agriculture. He pioneered computer-balance feed rations and no-till drill crop-planting equipment to minimize soil erosion. Albert also experimented with non-conventional feeds such as sake waste, chocolate bean hulls and avocado pits. He was among the first to milk three times per day, based on his kibbutz experiences in Israel. And, of course, he’s the first California dairyman to go organic.

Brother Michael, who is 27, started working in the family business earlier this year. Before that he was a job counselor and job developer for Jewish Vocational Services of San Francisco, working primarily with Russian immigrants. He learned Russian at UC Santa Cruz. “I decided I needed to learn a language –I was dreadfully ignorant– and I was interested in international politics. I never figured I would ever use it. But as soon as I graduated from college I found myself propelled into an internship working for Soviet Jewry” He spent four months in Leningrad in the winter of ’89, then a year in Israel. Upon his return, he says, “I wanted to work in the Jewish community and make use of my Russian.”

Michael’s short version of the family history: “My dad’s a German Jew and my mom’s Dutch (also Jewish). Her family got out of Holland three months before the Nazis invaded. She grew up in New York. My dad’s mother was born in San Luis Obispo. Her parents had come over from Germany to find a new life and they started a general store in San Luis Obispo in the 1800s when San Luis Obispo was bigger than LA. Then there was a big drought and her family decided to move back to Germany at the turn of the century. My dad’s father had a PhD in agriculture, but he died at the end of World War I. So my dad grew up in Germany, in the city of Hamburg. In 1936, with the fear of Nazism, my dad –being a good Zionist from a family that was active in the early years of the Zionist movement– studied agriculture and went to Palestine. He was there for a short time and suddenly got a telegram saying ‘Come quick we’re drilling for oil’ on land that had been left him by his grandparents in San Luis Obispo. So he comes over to America and there’s not a drop of oil and his mom’s really happy because it’s not good to have too much money. And he stayed in America, studied dairy husbandry at UC Davis and Berkeley, and came up here and bought the farm in 1941.

“My parents have done so much for environmentalism and agricultural preservation and building unity between conservationists and ranchers and farmers. I have a lot of respect for them. They’ve worked hard to do something out here. You know, farming’s a marginal business in general. Very few make a profit. And we’ve decided to put everything on the line –the dairy, the creamery, our way of life. This is a do-or-die operation. It’s very brave of my parents to do it at their age. My brother, too. He’s got a lot of chutzpah. He’s also put everything on the line [to produce organic milk in reusable bottles].”