In May, 1999, two men who ran CHAMP, a cannabis dispensary in San Francisco’s Castro district —Ken Hayes, then 33, and Mike Foley, 34— were arrested in Petaluma, along with Hayes’s pregnant girlfriend, Cheryl Sequoia. Hayes had rented a house with a barn on two acres in the former Egg Capital of the World, set up an indoor grow in the barn, and built six small greenhouses framed with PVC pipe snd covered with plastic. Running six 1,000-watt lights in the barn resulted in a high PG&E bill, which triggered a raid led by Sonoma County Sheriff’s Deputy Steve Gossett. The narcs netted 899 plants in various stages of growth, 14 lbs of dried herb, a pound of hashish, equipment for making hash oil, and $3,700 in cash. Also seized was a .22 caliber rifle that Hayes said he’d gotten because raccoons were raiding the chicken coop.

Sonoma County District Attorney Mike Mullins charged the defendants with cultivation with intent to sell, which could mean three-to-five years in prison, and conspiracy to make hash oil, which could mean seven. Hayes was represented by Bill Panzer, an Oakland-based lawyer who had co-authored Proposition 215, the ballot initiative by which California voters had legalized the medical use of marijuana in 1996. Foley’s lawyer, Nicole DeFever, was a young associate at Tony Serra’s San Francisco office. Soon after Sequoia hired the formidable Chris Andrian of Santa Rosa, charges against her were dropped. “They didn’t want to face Chris Andrian in court,” Panzer explains.

Panzer got the hash-oil-manufacturing charge thrown out at the preliminary hearing by convincing Superior Judge Robert Boyd that the statute, which had been written with meth labs in mind, did not apply to cannabis. (Panzer says he was fortunate —subsequent rulings on this question would go the other way.) The defense contended that Hayes and Foley were growing for the 1,280 members of CHAMP and that the scant sales records confiscated by the raiders showed payments that covered expenses, not profits.

Panzer asked San Francisco DA Terence Hallinan to testify and he readily agreed. “Terence was wonderful,” Panzer recalls. “He had been the one DA who supported 215, he believed in it, and he put his money where his mouth was. Part of our argument was ‘entrapment by estoppal.’ He testified that Ken had come to him and that he had advised Ken that the best way for a caregiver to be in compliance with the law was to grow it yourself. And Ken relied on Terence’s advice that if you grow it yourself within the state of California it would be legal.”

In her opening statement Claeys had said, “We have no problem with the club. It did some good things. This case is not about whether cannabis should be used for medical purposes, or not. This is a sales case. They were straight out selling marijuana for money.” Although almost no financial records had been found, the prosecution estimated that the raid had netted a half million dollars worth of product. The prosecution’s key witness was Gossett, who had led the raid. During his three days of testimony, Gossett alleged that one person could not be caregiver to twelve hundred people, that Hayes was profiting greatly from his arrangement with CHAMP, and that he was also selling to non-members. On cross-examination, Panzer asked “What kind of Ferrari does Mr. Hayes own?” Gossett acknowledged that Hayes drove “a beat-up truck and an old red Mazda.” Why, Panzer asked, would Hayes sell to non-members if he was profiting on sales to CHAMP? “Some people just get a thrill out of dealing dope,” Gossett replied.

The case would turn on the definition of “caregiver” under the law created by Prop 215. Claeys contended that Hayes and Foley had not “consistently assumed responsibility for the housing, health, or safety” of CHAMP members. The defense countered that the club provided counseling, massage, nutritious food, and above all, a place to socialize with other seriously ill people.

As Hallinan went to take the stand in a Santa Rosa courtroom on March 28, 2000, he patted Hayes on the shoulder. He testified that he had met with the defendant “four to six times” and that he had visited CHAMP three times to observe their procedures. “I think what Ken Hayes was doing was protected by Proposition 215,” Hallinan said. “I would say he was the most helpful of all the people involved in the medical marijuana movement.” Claeys tried to embarrass Hallinan by getting him to read aloud his Yes-on-215 ballot argument, which said the measure “only allows marijuana to be grown for a patient’s personal use. Police officers can still arrest anyone who grows too much or tries to sell it.”

Veteran observers could not recall a precedent for such a direct clash of two district attorneys in court. The situation was somewhat embarrassing to your correspondent, because Mullins had been my daughter’s soccer coach and I knew him to be a very decent man. Plus his kindly wife had been a teacher’s aide in my sons’ kindergarten class. Compounding the family-feud aspect of the proceedings, Mullins assigned the case to a young deputy DA, Carla Claeys, who had been an intern in the San Francisco DA’s office under Hallinan in 1996 when she was a third-year law student. Mullins was quoted in the Press Democrat saying that Hallinan was entitled to his interpretation of Prop 215, but, he added “Why not grow it in Golden Gate Park? What entitles them to use Sonoma County?” And he accused the defendants of having “a profit-making motive.”

It took the jury less than five hours to reach a verdict of not guilty. Juror Chris Walton told reporters that, as she and other saw it, the central question was whether Hayes and Foley could have legitimately been caregivers to more than 1,000 patients. What swayed them was the fact that a doctor or dentist might have more than 1,000 patients in their practice. “You guys are really serving a need and the laws have to change,” she told the greatly relieved defendants.

Freedom enabled Mike Foley in 2001 to co-found, with his partner Robin Few, a very good dispensary on 10th Street in San Francisco. Hung across the building was a large sign that read, simply, “The government is lying.” I thought it was the true message of the movement, because the government was and is lying about much more than marijuana. And speaking of lying…

“The prosecution called only one other witness, Steve Gossett, a deputy sheriff who heads Sonoma County’s marijuana investigations unit and is known as a zealous drug warrior. Gossett testified that he had visited Mikuriya at an office in Oakland in January ’03 and obtained a letter of approval by claiming to suffer from stress, insomnia, and shoulder pain so severe it kept him from holding a job for several years. The stress, Gossett said he’d told Mikuriya, was exacerbated by a pending marijuana possession case involving 54 grams.

“In the course of testifying about the fake history he had provided to Mikuriya, Gossett said ‘I lied on a lot of issues and I told the truth on a lot of issues… It’s hard to remember lies.’

“Which caused someone in the vicinity of the defense table to mutter ‘God damn!’

“Which caused Gossett to stop talking and look pained. When asked by the judge to continue, Gossett said somberly, ‘Somebody just took the Lord’s name in vain.’ After a few beats he gathered himself and resumed his testimony.”

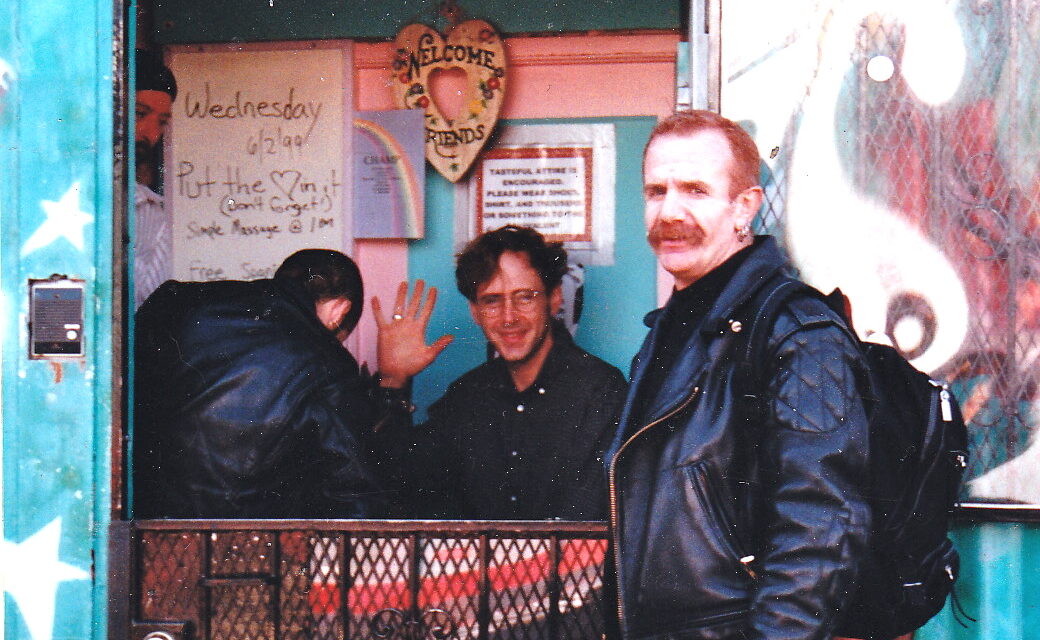

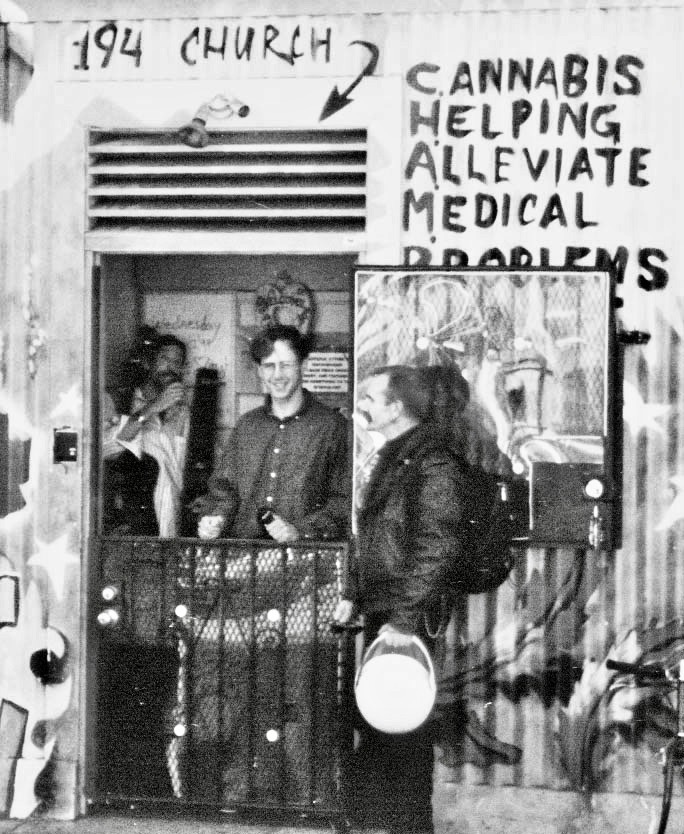

Ken Hayes (center) at the entrance to CHAMP. The second floor of 194 Church Street was the scene of Dennis Peron’s San Francisco Cannabis Buyers’ Club from 1992 through early 1995 (when the membership outgrew the space and Dennis leased 1444 Market Street).

Bonus track: https://youtu.be/1DB5r13Cc9M