April 10 By O’S News Service A paper published today in The Journal of the Royal Society Interface, Entrapment of bed bugs by leaf trichomes inspires microfabrication of biomimetic surfaces, resonates strongly with the medical marijuana story. In both cases plant-based folk remedies that had been recognized in the scientific literature fell into disuse after World War Two but are being appreciated again. In both cases the source of benefit has been traced to the trichomes —tiny hairs on the plants’ leaves and flowers. In both cases leading scientists are trying to develop patentable synthetics and hoping to equal the effectiveness of the plants.

The insecticide abilities of bean plants were known to peasants in the Balkans, who used to strew bean leaves on the floor of an infested room and then collect them in the morning —full of bugs— for burning. The effectiveness of the method had been reported in journal articles. According to the new study by Megan Szyndler of UC Irvine and colleagues,

“The decline of bedbug infestations in the 1940s and 1950s following the application of DDT and other potent pesticides legal at the time, and the distraction of the Second World War undoubtedly prevented the 1943 report, ‘The action of bean leaves against the bedbug’ [by HH Richardson in the Journal of Economic Entomology] from gaining as much attention as it would have otherwise.”

Just like the medical uses of Cannabis —”forgotten” in the ’40s, as the petrochemical sector became dominant in the economy.

Szyndler and her co-workers at UC Irvine and the University of Kentucky are not advocating immediate, widespread distribution of bean leaves by produce vendors for use against the bedbug epidemic. They have been studying the insecticide mechanism of the leaves in order to develop a synthetic alternative. Their paper is mostly devoted to efforts to develop a surface with artificial trichomes that can entangle bed bugs.

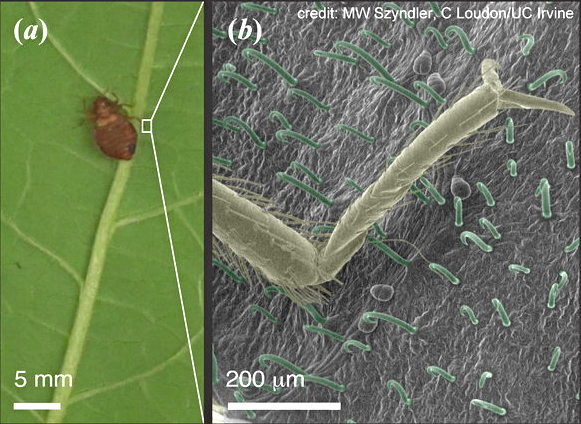

The bean’s trichomes are not topped with bulbous little glands. (The Cannabis plant also has non-glandular trichomes, prevalent on its fan leaves, that probably have an anti-insect effect.) The bean trichomes are shaped like barbless fish hooks and ensnare bedbugs mechanically, by hooking them and piercing them at junctures where their legs bend and the cuticle is thinner. Szyndler’s team filmed the process.

“Incidents of momentary or prolonged struggling by the bug as one or more legs were stuck in place were tabulated. The number of locomotory cycles until a bug experienced a momentary snag and until entrapment by a leaf were counted. One locomotory cycle refers to a single step taken by each of the six legs.”

The authors describe the fatal entrapment in vivid prose:

“As a bed bug walked on a leaf, entanglement of any legs by trichomes caused a visible change in its walking behaviour… Bed bugs continued to struggle after being pierced by a trichome, and the struggling movements often led to more piercings of the bug on the same or additional legs… Impaled bugs struggled, but were only rarely able to generate enough force to pull free of a piercing trichome (by breaking the trichome or ripping the insect cuticle), and usually immediately got recaptured on the leaf.”

Two types of entanglement were observed:

“a momentary snag of a leg with the bug able to break away… and a more lengthy and irreversible snag in which a visibly struggling bug is unable to pull away and is therefore considered ‘trapped’ by the leaf.”

Getting trapped involves a “piercing’ —a clear and unambiguous penetration of the insect cuticle by the trichome tip,” whereas the momentary snag involves “hooking” by the trichomes. In other words, the bug can break a tackle. But not for long.

It typically took only nine locomotory cycles for a bug to get trapped on a leaf. Ninety percent were trapped within 19 cycles. On average, a leaf-ensnared bug had 3.8 damaged legs.

Szyndler’s team worked with kidney beans raised from seeds (Johnny’s Seeds, product 2554). But the paper does not end with a call for produce vendors to stock bean leaves. More than half the article is devoted to the scientists’ attempts to develop “biomimetic surfaces” by making a negative mold, using the plant leaf as the positive.

“The moulding process generated synthetic trichomes that were indistinguishable from the natural trichomes, with the proper aspect ratio and sharpness of tips, arranged with the same density, orientation and height seen on the natural leaves… Various epoxies and glues with different hardening rates and resin-to-hardener ratios were used in order to generate artificial trichomes with mechanical properties that span the largely uncharacterized properties of natural trichomes… Material used to generate our synthetic surfaces overlap in material properties with plant cell walls.”

But darned if “These synthetic surfaces snag the bed bugs temporarily but do not hinder their locomotion as effectively as real leaves… Occasionally bugs were temporarily hooked on our fabricated surfaces (45 out of 158) bugs) but they were never pierced (0 out of 158 bugs).”

The authors note “the lack of any evolutionary association between bed bugs and kidney bean plants.” Could it be that bedbug-killing ability was one of the qualities that human beings used to breed for when crossing bean plants? Bedbugs have been sucking our blood since before we were sapiens.