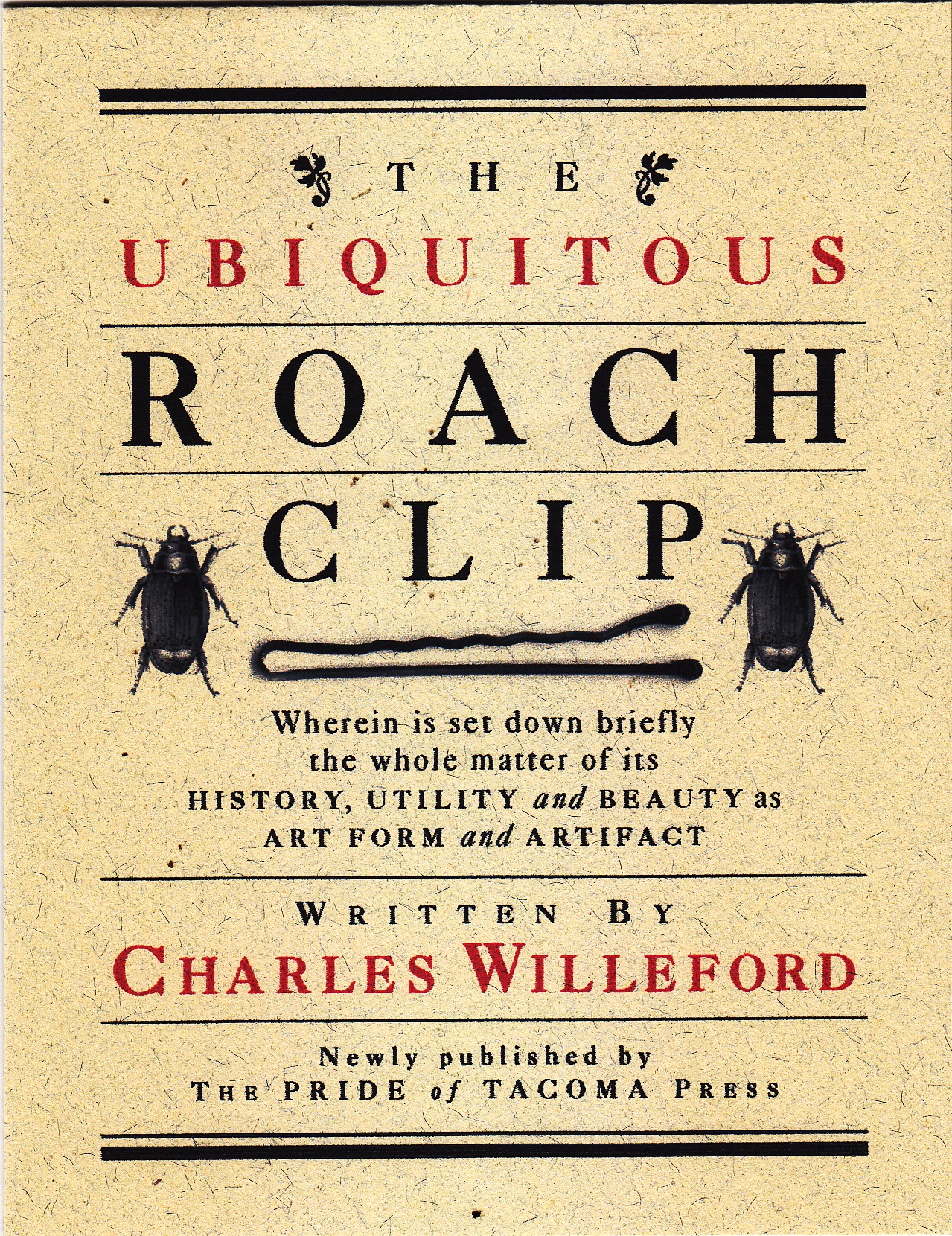

IN 2003 the Pride of Tacoma Press published a limited edition (150 copies) of a piece written by Charles Willeford in 1973 called “The Ubiquitous Roach Clip.” Willeford is a very sardonic and funny writer —a realist— who died in 1988 at the age of 69.

Wikipedia describes him as “an author of fiction, poetry, autobiography, and literary criticism, Willeford is best known for his series of novels featuring hardboiled detective Hoke Moseley. The first Hoke Moseley book, Miami Blues (1984), is considered one of its era’s most influential works of crime fiction. Film adaptations have been made of three of Willeford’s novels: Cockfighter, Miami Blues, and The Woman Chaser.”

His occupations are listed as “writer, college professor, magazine editor, boxer, actor, horse trainer, radio announcer, U.S. Air Force master sergeant, U.S. Army master sergeant.” We’re looking into the context in which Willeford published “The Ubiquitous Roach Clip” in ’73. Here it is:

As a general historical rule, the evolution of an art form is a slow and gradual process. Man, the tool-maker, out of need, fashions first a field expedient; the refinement, embellishment and decoration usually take a great many years to develop.

But such is not the case with the roach clip. In a relatively short period, beginning in the early 1960s, the roach clip has metamorphosed from a split match (the “Jefferson Airplane”) to the swirling curves and curvatures of Baroque and Art Nouveau. Indeed, the 1973 roach clip is a beautiful thing to behold (especially if one is holding).

First, the need: why is the roach clip so necessary in our contemporary weed culture?

There is a common, jointly-hold belief (whether it is true or not is immaterial) that the shorter the hand-rolled stick becomes, the better it gets. The shorter the c igarette, you see, the more packed the residue —in tars, resins, ashes, bits of seeds, and essence cannabis. Therefore the last and final drag, all residue darkly present, is surely the greatest toke of the entire cigarette. Besides, Mary Jane is an expensive broad, and it is certainly Un-American not to get one’s money’s worth.

As the cigarette burns down and down (after it passes the half-way mark the stick becomes a butt, or roach) the weed becomes warmer and warmer, and the last three-quarters of an inch —the best part of all— becomes too hot to handle with the naked fingers.

A roach clip is needed, a device that will keep the fingers from burning, and a clamp that will clutch the roach gently enough not to rip through the now dampened paper and still allow the even flow of smoke ‘n toke.

Initially, a bent paper match in the form a “V” was a hasty field expedient, which was quickly followed by the split wooden match. These crude implements did the job, perfunctorily, but they were not quite satisfactory. The width of a kitchen match is much too narrow for a firm finger grip, especially when one is passing the roach from hand to hand during a shared experience.

The bobby pin was much better, a natural development as women were drawn inevitably into the weed culture. With one flat interior side, and one bumpy side, the bobby pin was an evolutionary milestone, and a far better roach clip than the ordinary office paper clip. The paper clip, however, which can be bent into various forms, depending upon the twisting skills and artistic inclination of the stone-age artist, held it own with the bobby pin for two or three years.

Today’s roach clip, beautiful, bejeweled and Baroque, is an eclectic design taking the best features of the bobby pin and the paper clip, with unlimited, if finite, possibilities still to come for jewelers who specialize in drug culture ornamentation.

At present, Baroque and Art Nouveau roach clips seem to be the most popular, if less practical than the simpler gold or brass clips with the simple cannabis leaf identification of purpose. (The latter, you see, do double duty as ear-rings and tie clips). Still to come is the Rococo, with tiny bits of decorative seashell, découpage, Pop Op, and Minimal roach clips.

At any rate, the Renaissance of the roach clip has been over for several years. It came out and disappeared in a cloud of smoke, and hardly anyone noted or regretted its passage.

Willeford was way ahead of his time. Nowadays —although the line between objective reporting and paid-for p.r. has been obliterated— every advance in paraphernalia technology is publicized in great detail. We trust that Willeford has found some companionable souls in Purgatory. Maybe they’re passing around a vaporizer in the shape of a pen called the “Honey Stick.” —F.G.