The President says there is a “War on Thanksgiving,” and he’s right. Although most people appreciate the occasion to see friends and family, and everybody enjoys a good dinner, and as individuals we might have much to be thankful for, there has definitely a rethinking of the founding mythology, a recognition that the European settlers committed genocide. Native Americans hold a National Day of Mourning. The New York Times ran an op-ed by historian Daniel Silverman November 23 setting the record straight:

“The Pilgrims did not enter an empty wilderness ripe for the taking. Human civilization in the Americas was every bit as ancient and rich as in Europe. That is why Wampanoag country was full of villages, roads, cornfields, monuments, cemeteries and forests cleared of underbrush. Generations of Native people had made it that way with the expectation of passing along their land to their descendants.

“Contrary to the Thanksgiving myth, the Pilgrim-Wampanoag encounter was no first-contact meeting. Rather, it followed a string of bloody episodes since 1524 in which European explorers seized coastal Wampanoags to be sold into overseas slavery or to be trained as interpreters and guides. The Wampanoags reached out to the Pilgrims not only despite this violent history, but also partly because of it.

“In 1616, a European ship conveyed an epidemic disease to the Wampanoags that over the next three years took a staggering toll on their population. Afterward, the Narragansett tribe to the west began raiding the Wampanoags. To answer this threat, Ousamequin wanted the English to serve the Wampanoags both as military allies and as a source of European weaponry. His use of Squanto (or Tisquantum) as a go-between with the Plymouth settlers also stemmed from the Wampanoags’ history of being raided by Europeans. Squanto knew English because he had spent years in captivity in Spain and England before orchestrating an unlikely return home shortly before the Mayflower’s arrival. Such dark themes are hardly the stuff of Americans’ grade school Thanksgiving pageants.

“The Thanksgiving myth also sanitizes the power politics of the Pilgrim-Wampanoag alliance. For years afterward, Ousmequin threatened rivals in and outside the Wampanoag tribe with violence from his English allies. Such intimidation played a far more important role in the Wampanoags’ alliance with Plymouth than the first Thanksgiving.”

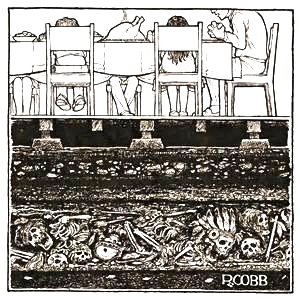

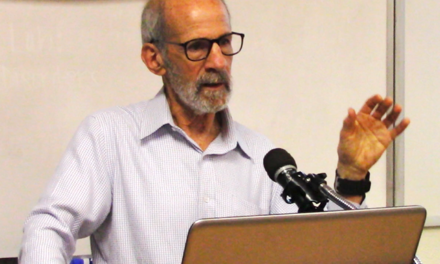

Ron Cobb’s Thanksgiving cartoon said it all more than 50 years ago. Cobb’s home base was the Los Angeles Free Press, one of the first “underground newspapers” to spring up back in the day. Its founder and editor, Art Kunkin, died in April of this year at the age of 91. Kunkin launched the Free Press in ’64. It provided detailed coverage of the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley (inspiring a lawyer named Max Scherr to launch the Berkeley Barb), the Watts uprising, the pot scene, the rise of La Raza, antiwar protests, women’s liberation, and every other strand of “the movement” of the ’60s.

According to Kunkin’s New York Times obit,

“By the end of the 1960s it had a robust circulation near 100,000. But Mr. Kunkin was beginning to encounter financial difficulties — partly as a result of his acquisition of a printing press, which became a financial burden, and partly as a result of his decision to publish, in August 1969, the names and addresses of 80 government narcotics agents. ‘There Should Be No Secret Police,’ the headline on that article read, but it led to lawsuits that crippled his operation…

“In 1973, while the mainstream American Society of Newspaper Editors was meeting in Washington, the underground press held a counterconvention across town. The two groups even got together for a joint session (as it were).

“’While besuited editors looked on uncomfortably,’ The Boston Globe reported ‘L.A. Free Press editor Art Kunkin passed out cider and marijuana before presenting an inventory of plots, crimes and assassinations he said had been ignored by daily newspapers.'”

Kunkin came from New York and graduated from Bronx Science in 1945. He was “an organizer for the Socialist Workers Party,” the Times obit recounts, “and acquired some journalism experience working on The Militant, the party’s newspaper, as well as other leftist publications. In the 1950s, after service in the Army, he worked as a machinist for General Motors and Ford… ‘I worked for five years in auto plants,’ he said in an interview… ‘and those factories are prisons. And from my experience, those people in there are radical as hell. But you never hear about that.'”

In a 1996 interview Kunkin said, “What made the difference between the alternative press in the 1960s and the mass media,” he said, “was that the mass media looked on all events as isolated — errors that the system could correct. The sense of the 1960s alternative press was that these issues were all connected, that they indicated a certain sickness of the society. And this sickness has not decreased.”

Kunkin’s retrograde message —”that these issues are all connected”— is worth repeating now that so many political activists are caught in a single-issue trap. The “entourage effect” applies in politics as well as in pharmacology. Maybe more. —Fred Gardner