After California voters legalized marijuana for medical use, Tod Mikuriya, MD, wanted to stage a reading of the 1937 hearing at which prohibition was debated by the US Congress. I “doctored” the script, using the text from the Congressional Record, with only a few minor cuts, and added a Narrator.

After California voters legalized marijuana for medical use, Tod Mikuriya, MD, wanted to stage a reading of the 1937 hearing at which prohibition was debated by the US Congress. I “doctored” the script, using the text from the Congressional Record, with only a few minor cuts, and added a Narrator.

Tod intended to read the part of Dr. William Woodward, whom he greatly admired. San Francisco District Attorney Terence Hallinan was going to read the part of Harry Anslinger, director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Graphics would be displayed on a screen behind the Narrator.

This is not dialogue from some movie in which actors smoke marijuana and pretend to go berserk. This is testimony that would be elevated to the level of a Congressional finding —the actual, factual truth, according to the United States government. It is a tragicomedy that has an impact on our lives to this day.

As the Great Playwright would have it, the historic hearings took on the three-act structure of a well-made drama. One, Treasury presents the case for federal prohibition to a confused House of Representatives. Two, an almost comic interlude as leaders of the hemp industry grapple with the news that their beneficial and useful product is deadly “marihuana.” Three, a principled physician argues against prohibition, only to be ignored and insulted by the politicians.

We never staged our reading of “Prohibition 37,” but we published the script in the Spring 2006 issue of O’Shaughnessy’s. Maybe someday somebody will make use of it.

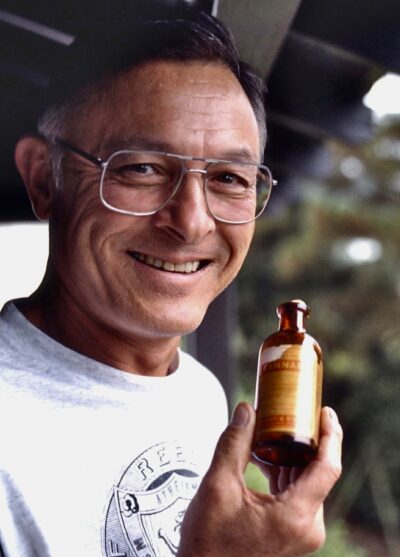

This photo by Michael Aldrich shows Dr. Mikuriya holding a bottle of Cannabis tincture manufactured prior to the 1937 prohibition by Sharp & Dohme —a major US pharmaceutical company. Those of us who came of age after World War Two were not taught that marijuana had medicinal uses and had been legally available. It was Tod who uncovered the suppressed history and opened our eyes to it. —Fred Gardner

Act One

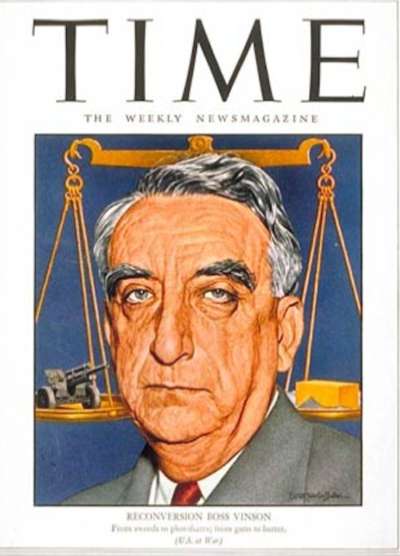

A swing band is playing “Nice work if you can get it” on the radio as the NARRATOR takes his place on a stool. CONGRESSMEN and WITNESSES take seats at a table. A place card gives each man’s name, party and state. (They are all men but can of course be played by women.) Committee members include Democrats Robert Doughton of North Carolina, the chairman; Fred Vinson of Kentucky; John Dingell and Roy Woodruff of Michigan; John McCormack of Massachusetts; Jere Cooper of Tennesee; Claude Fuller of Arkansas; Wesley Disney of Oklahoma. The Republicans include David Lewis of Maryland; Daniel Reed and Frank Crowther of New York.

The first witness is Clinton Hester, a lawyer for the U.S. Treasury Department, a pinstripe-suit type. The music fades.

NARRATOR: Act one, scene one: The Marijuana-as-Machine-Gun Ploy. What you’re about to hear is taken from the Congressional Record (As if reading) “Tuesday, April 27, 1937. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, Hon. Robert L. Doughton, presiding.” (To the audience) Doughton was a Democrat from North Carolina. In 1937 the South was solidly Democratic —and solidly segregationist. At the insistence of the Southerners in Congress, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal did not provide social security for farm workers and domestic servants —Black people, mainly.

DOUGHTON (while a PAGE distributes copies of the bill): The committee will come to order. The meeting this morning has been called for the purpose of considering H.R. 6385, introduced by me on April 14, 1937, a bill to “impose an occupational excise tax upon certain dealers in marijuana, to impose a transfer tax upon certain dealings in marijuana, and to safeguard the revenue therefrom by registry and recording.” This bill was introduced by me at the request of the Secretary of the Treasury.

NARRATOR: The Secretary of the Treasury in 1937 was Henry Morgenthau, a New York banker from a prominent German-Jewish family. Morgenthau had been a friend and supporter of Roosevelt long before FDR became president. He was appointed in 1933 to succeed Andrew Mellon, a WASP banker from Pittsburgh. When Morgenthau arrived at Treasury, he did not replace the ambitious young bureaucrat whom Mellon had put in charge of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics… Harry J. Anslinger.

DOUGHTON: Representatives of the Treasury Department are here this morning to explain the bill. Mr. Clinton Hester, assistant general counsel for the Treasury Department will be the first witness to be heard in behalf of the proposed legislation.

HESTER: Mr. Chairman and members of the Ways and Means Committee, for the past two years the Treasury Department has been making a study of the subject of marijuana. A drug which is found in the flowering tops, seeds and leaves of Indian hemp, and is now being used extensively by high school children in cigarettes. Its effect is deadly.

NARRATOR: The direct effects of inhaling or ingesting marijuana are not deadly and never have been. The very first statement from the government’s first witness is untrue. Will anybody request documentation?

HESTER: The leading newspapers of the United States have recognized the seriousness of this problem and many of them have advocated Federal legislation to control the traffic in marijuana. In fact, several newspapers in the city of Washington have advocated such legislation. In a recent editorial the Washington Times stated: “The marijuana cigarette is one of the most insidious of all forms of dope, largely because of the failure of the public to understand its fatal qualities. The nation is almost defenseless against it, having no federal laws to cope with it, and virtually no organized campaign for combating it. The result is tragic. School children are prey to peddlers who infest school neighborhoods. High school boys and girls buy the destructive weed without knowledge of its capacity for harm, and conscienceless dealers sell it with impunity. This is a national problem and it must have national attention. The fatal marijuana cigarette must be recognized as a deadly drug, and the American children must be protected against it.”

NARRATOR: And I thought it was only in our time that politicians started doing everything “for the children.” Guess not.

HESTER: As recently as the 17th of this month there appeared in the Washington Post an editorial on this subject, advocating the speedy enactment by Congress of this very bill. I quote: “It is time to wipe out the evil before its potentialities for national degeneracy become more apparent. The legislation just introduced in Congress by Representative Doughton would further this end. Its speedy passage is desirable.” The purpose of House Resolution 6385 is to employ the federal taxing power, not only to raise revenue from the marijuana traffic, but also to discourage the current and widespread undesirable use of marijuana by smokers and drug addicts, and thus drive the traffic into channels where the plant will be put to valuable, industrial, medical, and scientific uses.

NARRATOR: In 1937, even the prohibitionists had to acknowledge marijuana’s industrial, medical and scientific uses. Anticipating opposition from businesses that used the plant as fiber, medicine, birdseed, and oil, the Treasury Department was prepared to offer some exemptions. A similar strategy had worked in 1914 when Congress passed the Harrison Act, placing a prohibitive tax on cocaine and opium transactions. Doctors, dentists, druggists, veterinarians and researchers were exempted —they only had to pay a token dollar a year and fill out onerous paperwork.

HESTER: The Harrison Narcotics Act was designed to accomplish these same general objectives with reference to opium and coca leaves and their derivatives. That act required all legitimate handlers of narcotics to register, pay an occupational tax, and file information returns setting forth the details surrounding their use of the drugs. It further provided that no transfer of narcotics (with a few exceptions, notably by practitioners in their bona fide practice and druggists who dispense on prescription) could be made except upon written order forms. Since no one except registered persons could legally acquire these order forms and since illicit consumers were not eligible to register, the order-form requirement served the double purpose of publicizing transfers of narcotics and restricting them to legitimate users.

LEWIS: The treatment of this subject, so far as constitutional basis is concerned, is about the same as the Harrison Narcotic Act…. I was thinking you might add this drug as an amendment to the Harrison Narcotic Act.

NARRATOR: Congressman Lewis asks a good question: Why didn’t the Treasury Department simply propose an addition to the Harrison Act, listing marijuana among the plants that had to be taxed? (Opening a copy of a book) This is a very good book called “The Marijuana Conviction”) by two law professors, Bonnie and Whitebread. According to them, in passing the Harrison Act, quote, “Congress was attempting to do indirectly that which it believed it could not do directly: regulate the practice of medicine and the intrastate sale and possession of drugs… The Supreme Court had allowed Congress to get away with this ruse, but only by a five-to-four margin.” Close quote.

HESTER: The Harrison Act has twice been sustained by the Supreme Court of the United States, and lawyers are no longer challenging its constitutionality. If an entirely new and different subject matter were to be inserted in its provisions, the act might be subject to further constitutional attacks.

LEWIS: On what basis did the justices who dissented question the constitutionality of the Harrison Act?

HESTER: The focal point of the attack was that the provision which limited the persons to whom narcotics could be sold clearly indicated that the primary purpose of the act was not to raise revenue, but to regulate matters which were reserved to the States under the 10th amendment.

NARRATOR: The 10th Amendment leaves the regulation of medicine up to the states. So when the U.S. Treasury Department decided to ban marijuana, they had to concoct a scheme to get around it. The slick lawyer who actually drafted the bill was an aide to Morgenthau named Herman Oliphant. His idea was to place a prohibitive sales tax on all marijuana sales —like the one Congress had recently placed on machine guns. Unlike the Harrison Act, which created a subset of citizens entitled to buy and sell opium and cocaine, the marijuana prohibition bill entitled all citizens to buy and sell it —but only if they registered each transaction with the government and paid the huge tax.

Below is a photo of Clinton Hester (right). Tod thought the gent at left was Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau.

HESTER: The proposed marijuana bill is something of a synthesis between the Harrison Act and the National Firearms Act… In order to obviate the possibility of an attack upon the constitutionality of this bill, it, like the National Firearms Act, permits the transfer of marijuana to non-registered persons upon the payment of a heavy transfer tax. The bill would permit the transfer of marijuana to anyone. It would impose a $100-an-ounce tax upon a transfer to a person who might use it for purposes which are dangerous and harmful to the public, just as the National Firearms Act permits a transfer of a machine-gun to anyone but imposes a $200 tax upon a transfer to a person who would be likely to put it to an illegal use. We’ve looked into the records in connection with the transfer tax in the Firearms Act, and we found that only one machine gun was purchased at $200 last year.

DINGELL: Legitimately?

HESTER: Yes. This bill would permit anyone to purchase marihuana as was done in the National Firearms Act in permitting anyone to buy a machine gun. But he would have to pay a tax of $100 per ounce of marijuana and make his purchase on an official order form. A person who wants to buy marijuana would have to go to the collector and get an order form in duplicate, and buy the $100 tax stamp and put it on the original order form there. He would take the original to the vendor, and keep the duplicate. If the purchaser wants to transfer it, the person who purchases the marijuana from him has to do the same thing and pay the $100 tax. That is the scheme that has been adopted to stop high-school children from getting marijuana.

NARRATOR: Is there anything new under the bureaucracy?

JENKINS: It seems to me your only burden is to prove, chemically, that this is a narcotic.

HESTER: We have to show that it is a drug.

JENKINS: If you show that, you have no question as to its being constitutional?

HESTER: That is right.

McCORMACK: In other words, it is a straight tax bill?

HESTER: That is right.

McCORMACK: And the other testimony you will introduce as to the character of this drug and its effect upon human beings is to justify what appears to be a high tax.

HESTER: That is right.

McCORMACK: Showing the justification for this from the tax angle. That is the theory upon which you are proceeding.

HESTER: That is the theory. Your statement is absolutely correct.

McCORMACK: What the results might be is of no concern to the courts. If we have the power to tax, the manner in which it is exercised is of no concern to the courts.

HESTER: That is right.

NARRATOR: In the 1930s Congress was asserting its power to legislate in areas that, for most of U.S. history, had been left up to the states.

VINSON: What is the fair market value, per ounce, of marijuana?

HESTER: In its raw state it is about one dollar per ounce, as a drug.

NARRATOR: The bygone age of the one-dollar ounce.

DINGELL: I would like to ask the witness whether the Treasury has had any contact with the pharmaceutical trade, and whether we have any word from them as to their attitude on this proposed legislation. Take, for instance, such concerns as Frederick Stearns; Park, Davis & Co; Burroughs-Welcome, and a number of others; have you had any word from them as to whether they are opposed to this legislation or not?

HESTER: I have not personally communicated with any of these people, but Commissioner Anslinger is in touch with them constantly. I might say, though, that this drug is rarely used by the medical profession and is not indispensable to that profession. Commissioner Anslinger will predict in his statement that it will be only a few years until marijuana will entirely disappear as a drug.

DINGELL: I have no intention of trying to place the commercial interests of the drug producers ahead of the general welfare or ahead of public health, but I wondered whether the Treasury had any word from the large drug manufacturers who are always, so far as I can ascertain, willing to cooperate with the Treasury.

HESTER: The drug manufacturers always cooperate with the Treasury Department in all these matters. This bill has been pending for some time and we have not had any word from them. NARRATOR: Although Merck and Eli Lilly and many other drug companies produced and sold cannabis-based tinctures and salves, these products didn’t bring in significant profits. The manufacturers had never marketed products of consistent potency, and doctors were reluctant to prescribe medicine that might be too weak or too strong. For pain reduction, opiates and barbiturates offered purity, consistency, and “precise dosage” (which is never really precise, given the variations in size and metabolism between individual patients).

DOUGHTON: Through what channel or agency is this drug in its deleterious form dispensed or distributed? Is it sold by druggists, or at grocery stores?

HESTER: I will answer your question, but I hope you will ask the same question of Mr. Anslinger, because he can speak more authoritatively on that phase of the subject. The flowered tops, leaves, and seeds, are smoked in cigarettes.

DOUGHTON: Is it carried generally by druggists?

HESTER: I do not think so, for this reason. It is very variable. It may affect you in one way, and me in another way, and then, too, there are many better substitutes.

DOUGHTON: And its use is deleterious?

HESTER: The smoking of it, yes. You can take the tops, leaves, and seeds and fix them in a way somewhat similar to tobacco. It is just about the same as tobacco. You can smoke it like tobacco.

DOUGHTON: Just as an illustration, suppose I were in the market for some of this drug, where would I find it?

HESTER: There are about 10,000 acres under cultivation by legitimate producers.

DOUGHTON: I want to know where it can be bought? When is it being sold?

LEWIS: Where do the victims get it?

REED: I think what the chairman wants to know is how the high-school children are able to get it. Is it true that there are illicit peddlers who hang around the high-school buildings, and as soon as they find out that there is some boy to whom they think they can sell it, they make his acquaintance?

HESTER: Yes, I read in the newspapers not long ago that a place on 12th Street was raided where a lady was selling marijuana.

LEWIS: Do legitimate companies make these cigarettes, or are they made in an illicit manner, like bootleg whiskey used to be made? Do reputable firms make these cigarettes?

HESTER: I would like to refer that question to Commissioner Anslinger.

NARRATOR: Act one, scene two: The Original Drug Czar. Harry Jacob Anslinger, was born in 1892, the eighth of nine children. He grew up in Western Pennsylvania. His mother had emigrated from Baden, Germany. His father had emigrated from Switzerland, where he had been a barber. When he couldn’t make a living at his trade, he went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad, which was then a major U.S. corporation —as you can see from the Monopoly board.

As a teenager Harry was in some kind of tussle and somebody threw a pear that hit him in the eye, causing a detached retina. He went to school part-time and worked for the railroad. Soon he was assigned to do security work. As a young investigator Anslinger helped win a big case for the company and was promoted to chief inspector.

He took two years of business classes at Penn State. He occasionally played the piano at silent-movie theaters (around 1914-15). His mother had hoped he’d become a concert pianist.

When the U.S. entered World War One Anslinger volunteered for the army but was ruled ineligible because of impaired vision in one eye. He became an officer in the Ordnance Reserve Corps and was rapidly promoted. He applied to and was hired by the U.S. State Department as an attaché in the American Legation at the Hague —a classic spot for intelligence agents. He spoke perfect German and good French, and he picked up Dutch quickly. (Henry Kissinger would also owe his career to speaking German and getting assigned to Army Intelligence.)

Anslinger claimed that towards the end of the war he insinuated his way into Kaiser Wilhelm’s entourage and delivered the message that the U.S. did not want the Kaiser to abdicate because it might lead to the Social Democrats coming to power. (But the Kaiser did step down.) In 1921 Anslinger was posted by the consular service to Hamburg. He married the former Martha Denniston, a niece —said to be the favorite niece— of Andrew Mellon, the Pittsburgh banker who had become Secretary of the Treasury under President Warren Harding. Martha had a 12-year-old son from a previous marriage.

Anslinger’s next posting was to a beautiful port city in Venezuela, La Guaira, which lies at the foot of a sheer, tropical mountain and along a crescent-shaped beach. Anslinger hated it, according to his biographer, John Williams, and bombarded the State Department with letters requesting a transfer. He got a transfer to Nassau, where his career as a Prohibition agent took off.

Consul Anslinger urged the British to crack down on the Bahamians running liquor to the U.S. At a conference in London he vividly recounted seeing ships leaving Nassau loaded with whiskey and returning empty. The Brits agreed to a protocol —ships going in and out of Nassau harbor would have to show paperwork. It became known as the “Anslinger Accord.” Andrew Mellon requested that the rising young star be transferred to Treasury so that he could make similar arrangements with Canada, France, and Cuba.

Anslinger became chief of the Prohibition Unit’s Division of Foreign Control (anti-smuggling). He attended conferences in London and Paris, and conducted inspections in Vancouver, Nova Scotia, Antwerp, and Havana.

In 1929 Anslinger was made Assistant Commissioner of Prohibition. He argued that Congress should amend the law to make it a crime to buy alcohol. (Only manufacture, sales and transportation had been Prohibited.) Anslinger wanted a second conviction to carry a mandatory minimum two years in prison and a $5,000 fine.

In 1930 Congress created a Federal Bureau of Narcotics (separate from the Prohibition Bureau but also part of the Treasury Department). The top contender to run the FBN, Levi Nutt, got embroiled in a scandal and Mellon named Anslinger Acting Commissioner. Harry then organized a lobbying campaign to get the job permanently. He had the backing of railroad magnates, William Randolph Hearst, the National Association of Retail Druggists, and the American Medical Association. He was appointed Narcotics Commissioner by Herbert Hoover in September, 1930, at the age of 38.

DOUGHTON: Mr. Anslinger, the committee will be glad to have a statement from you at this time. Will you state your full name and the position you occupy with the Treasury Department?

ANSLINGER: My name is H. J. Anslinger. I am commissioner of narcotics in the Bureau of Narcotics, in the Treasury Department. Mr. Chairman and distinguished members of the Ways and Means Committee, this traffic in marijuana is increasing to such an extent that it has become the cause for the greatest national concern. This drug is as old as civilization itself. Homer wrote about it as a drug which made men forget their homes and that turned them into swine. In Persia, a thousand years before Christ, there was a religious and military order founded which was called the Assassins, and they derived the name from the drug called hashish, which is now known in this country as marijuana. They were noted for their acts of cruelty and the word “assassin” very aptly describes the drug.

NARRATOR: Historian Tod Mikuriya, MD, had a different explanation: “They’d smoke hashish the night before battle to overcome anxiety and get to sleep.”

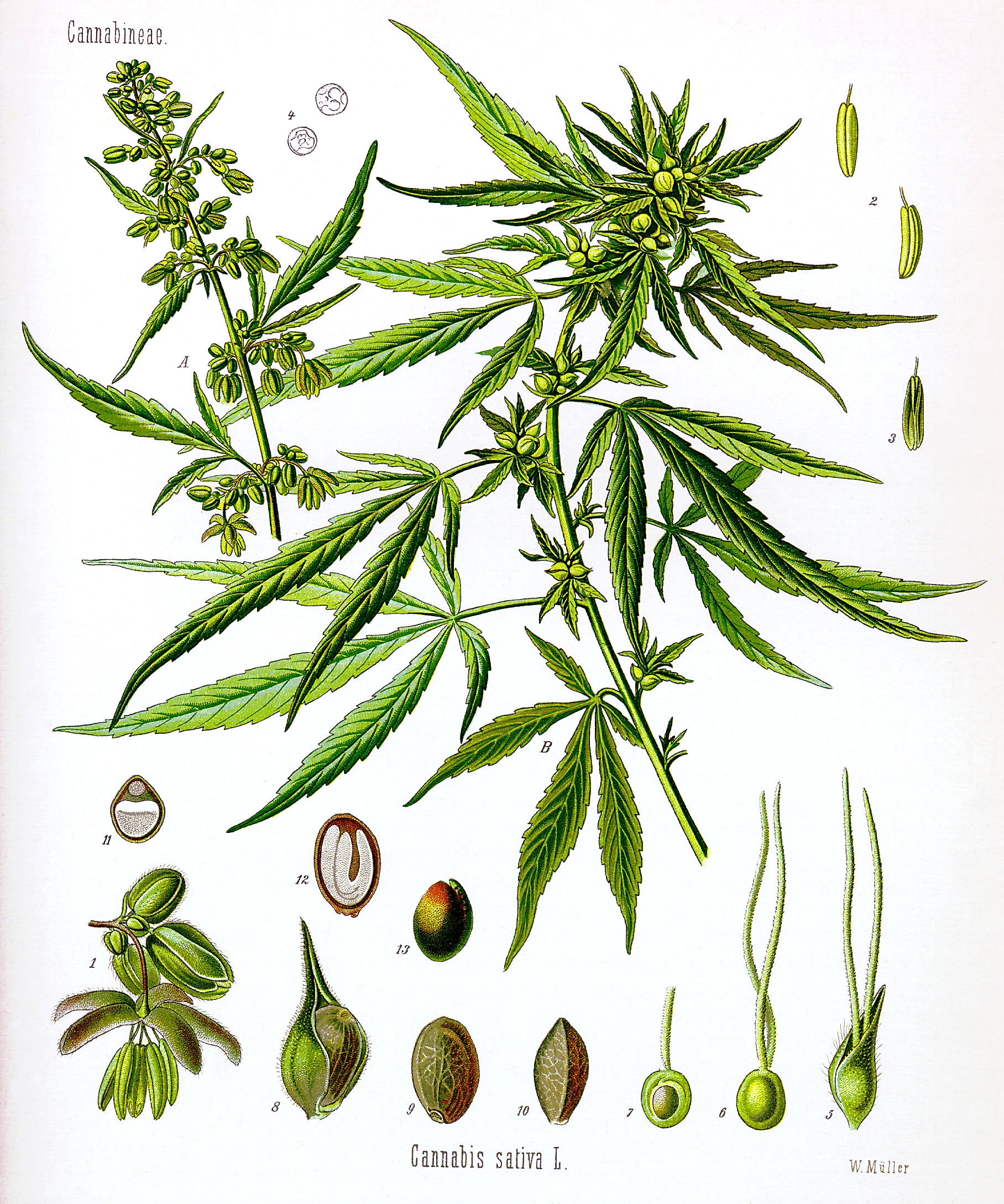

ANSLINGER: Marijuana is the same as Indian hemp, hashish. It is sometimes cultivated in backyards. Over here in Maryland some has been found, and last fall we discovered three acres of it in the Southwest… It is sometimes found as a residual weed and sometimes as the result of a dissemination of birdseed. It is known as cannabis Americana, or cannabis Sativa. Marijuana is the Mexican term for cannabis Indica. We seem to have adopted the Mexican terminology, and we call it marihuana, which means “good feeling.” In the underworld it is referred to by such colorful, colloquial names as reefer, muggles, Indian hay, hot hay, and weed. It is known in various counties by a variety of names.

NARRATOR: Some say the Treasury Department chose the term “marijuana” —instead of “Cannabis” or “hemp”— because they figured anti-Mexican prejudice would attach to it. In official documents, including the Congressional Register from which we’re reading, “marijuana” was spelled with an h instead of a j — as if the U.S. government was going to teach those Mexicans how to spell.

LEWIS: In literature it is known as hashish, is it not?

ANSLINGER: Yes, sir. At the Geneva Convention in 1895 the term “cannabis” included only the dried flowering or fruiting top of the pistillate plant as the source of the dangerous resin… But research has shown that this definition is not sufficient, because it has been found by experiment that the leaves of the pistillate plant as well as the leaves of the staminate plant contain the active principle up to 50 percent of the strength prescribed by the U.S. Pharmacopoeia… As a matter of fact, the staminate leaves are about as harmless as a rattlesnake.

NARRATOR: The stamen is the organ that produces pollen for the male plant. The Commissioner is comparing the leaves of the male cannabis plant to a rattlesnake. Anslinger says “research has found…” in exactly the way establishment experts use that phrase today —as if the ultimate truth had been determined.

ANSLINGER: In medical schools the physician-to-be is taught that without opium, medicine would be like a one armed-man. That is true, because you cannot get along without opium. But here we have a drug that is not like opium. Opium has all of the good of Dr. Jekyll and all the evil of Mr. Hyde. This drug is entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured.

NARRATOR: Robert Louis Stevenson didn’t think so.

REED: I want to be certain what this is. Is this the weed that grows wild in some of the Western States which is now called the loco weed?

ANSLINGER: No, sir, that is another family.

DINGELL: That is also a harmful drug-producing weed it not?

ANSLINGER: Not to my knowledge: it is not used by humans.

DOUGHTON: In what particular sections does this weed grow wild?

ANSLINGER: In almost every state in the Union today.

REED: What you are describing is a plant which has a rather large flower?

ANSLINGER: No, sir, a very small flower.

REED: Is it not Indian Hemp?

ANSLINGER: It is Indian Hemp. We have some specimens here.

ANSLINGER passes around some leafy stalks of marijuana.

VINSON: When was this brought to your attention being a menace among our own people?

ANSLINGER: About ten years ago.

VINSON: Why did you wait until 1937 to bring in a recommendation of this kind?

ANSLINGER: Ten years ago we only heard about it throughout the Southwest. It is only in the last few years that it has become a national menace. It has grown like wildfire, but only become a national menace in the last three years.

NARRATOR: In the early 20th century, in the Southwest, the ranchers and bankers wanted the Mexican fieldhands kept in their place —not functioning as citizens with full rights. The fact that Mexicans smoked marijuana distinguished them from the gringos. Criminalizing marijuana gave law enforcement grounds to bust and control them. By the 1920s the herb was gaining popularity among Black people in New Orleans, where a racist district attorney used it to keep them in their place. And just as jazz came up the river from New Orleans, so did marijuana. By the 1930s it was obtainable in Midwestern and northern industrial cities, where Mexican and Black workers were competing with European-Americans for blue-collar jobs.

ANSLINGER: It is only in the last two years that we had a report of seizures anywhere but in the Southwest. Last year New York State reported 195 tons seized. Before that I do not believe New York could have reported one ton seized. Let me quote from this report to the League of Nations: “The discussion disclosed that, from the medical point of view in some countries, the use of Indian hemp in its various forms is regarded as in no way indispensable and that it is therefore possible that little objection would be raised to drafting limitations upon medical use of derivatives.” That is only last year.

Here is what Dr. J. Bouquet, hospital pharmacist at Tunis, and inspector of pharmacists at Tunis, says. He is the outstanding expert on cannabis in the world. He says, “to sum up, Indian hemp, like many other medicaments, had enjoyed for a time a vogue which is not justified by the results obtained. Therapeutics would not lose much if it were removed from the list of medicaments.” That comes from the greatest authority on cannabis in the world.

NARRATOR: This supposedly great authority, Bouquet, went on to write, “The basis of the Moslem character is indolence; these people love idleness and daydreaming, and to the majority of them work is the most unpleasant of all necessities. Inordinately vainglorious, thirsting for every pleasure, they are manifestly unable to realize more than a small fraction of their desires: their unrestrained imagination supplies the rest. Hemp, which enhances and stimulates the power of imagination, is the narcotic best adapted to their mentality.”

McCORMACK: What are its first manifestations, a feeling of grandeur and self-exaltation, and things of that sort?

ANSLINGER: It affects different individuals in different ways.

NARRATOR: This is true.

ANSLINGER: Some individuals have a complete loss of a sense of time or a sense of value. They lose the sense of place. They have an increased feeling of physical strength and power. Some people fly into a delirious rage and they are temporarily irresponsible and may commit violent crimes. Other people will laugh uncontrollably. It is impossible to say what the effect will be on any individual. Those research men who have tried it have always been under control. They have always insisted on that.

McCORMACK: Is it used by the criminal class?

ANSLINGER: Yes, it is. It is dangerous to the mind and body, and particularly dangerous to the criminal type, because it releases all of the inhibitions. I have here statements by the foremost expert in the world talking on this subject. “Does Indian hemp —cannabis sativa— in its various forms give rise to drug addiction?” This is from the report by Dr. J. Bouquet, Tunis, to the League of Nations. “The use of cannabis, whether smoked or ingested in its various forms, undoubtedly gives rise to a form of addiction, which has serious social consequences: abandonment of work…

NARRATOR: The boss’s least favorite image.

ANSLINGER” “…propensity to theft and crime, disappearance of reproductive power.”

NARRATOR: Not true.

ANSLINGER: I will give you gentlemen just a few outstanding evidences of crimes that have been committed as a result of the use of marijuana. Here is a gang of seven young men, all seven of them, young men under 21 years of age. They terrorized central Ohio for more than two months and they were responsible for 38 stick-ups. They all boast that they did those crimes while under the influence of marijuana.

LEWIS: Does it strengthen the criminal will? Does it operate as whiskey might, to provoke recklessness?

ANSLINGER: I think it makes them irresponsible. A man does not know what he is doing. (Shuffling papers) Here is one of the worst cases I have seen. The district attorney told me the defendant in this case pleaded that he was under the influence of marijuana when he committed that crime, but that has not been recognized. We have several cases of that kind. There was one town in Ohio where a young man went into a hotel and held up the clerk and killed him, and his defense was that he had been affected by the use of marijuana. As to these young men I was telling you about, one of them said if he had killed somebody on the spot he would not have known it.

In Florida a 21-year old boy under the influence of this drug killed his parents and his brothers and sister. The evidence showed that he had smoked marijuana. In Chicago recently two boys murdered a policeman while under the influence of marijuana…

NARRATOR (emphatically): This is not a ludicrous movie in which actors smoke marijuana and pretend to go berserk. This is sworn testimony by Treasury Department officials that the United States Congress is going to act on. This is the basis for the federal prohibition that continues to this day.

ANSLINGER: Not long ago we found a 15-year-old boy going insane because, the doctor told the enforcement officers, he thought the boy was smoking marijuana cigarettes… Colorado seems to have had a lot of cases of violence recently. In Alamosa county and in Huerfano county the sheriff was killed as the result of the action of a man under the influence of marijuana. Recently in Baltimore a young man was sent to the electric chair for having raped a girl while under the influence of marijuana.

McCORMACK: Are you acquainted with the report of the public prosecutor at New Orleans in 1931?

ANSLINGER: Yes, sir. I am going to introduce it into the record.

McCORMACK: That was a case where 125 out of 450 prisoners were found to be marijuana addicts, and slightly less than one half of the murderers were marijuana addicts, and about 20 percent of them were charged with being addicts of what they called “merry wonder.”

ANSLINGER: That is the same thing.

McCORMACK: You are acquainted with that?

ANSLINGER: Yes, sir. That is one of the finest reports that has been written on marijuana… by the district attorney, Eugene Stanley. (He reads from it) “The United States government, unquestionably, will be compelled to adopt a consistent attitude towards this drug, and… to give Federal aid to the states in their effort to suppress a traffic as deadly and destructive to society as the traffic in the other forms of narcotics now prohibited by the Harrison Act.”

NARRATOR: Eugene Stanley was the district attorney of New Orleans, Louisiana —an ambitious prosecutor trying to find a scapegoat for an extended wave of robberies that were actually a result of the alcohol prohibition. The marijuana users he charged were disproportionately Black. In the 1920s this same crusader had closed the clinics at which doctors had been treating opium addicts effectively by giving them maintenance doses.

DOUGHTON: How many states have laws in reference to marijuana?

ANSLINGER: Every state except the District of Columbia. Last year there were 15 dealers arrested here for peddling marijuana and they had to be prosecuted for pharmacy without a license. (DR. WOODWARD reacts, writes himself a note on a legal pad.)

DOUGHTON: The states now all do cooperate?

ANSLINGER: Every one of them, yes sir. But they do not all have central enforcement agencies.

DOUGHTON: With this uniform state legislation, why can they not stamp this out? What progress are they making?

ANSLINGER: They are making some progress, as indicated by the 338 seizures made last year. The state of Pennsylvania destroyed 200,000 pounds.

JENKINS: If each state has a law on this subject, I wonder why that does not reach it.

ANSLINGER: It does reach it. But we get requests from public officials from different states, and I will name particularly the states of Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Louisiana and Oklahoma that have urged federal legislation for the purpose of enabling us to cooperate with the several states.

McCORMACK: This is a tax measure, and we might as well get the revenue out of it that enables the federal government to cooperate with the states in connection with the state activities.

NARRATOR: “We might as well get the revenue out of it.” How forthright!

ANSLINGER: And you get a certain uniformity. You also get to help the local police, and they always want it. You also get to help the state police, and they always ask for this help. Whenever they find marijuana, the first place on which they call for help is the federal narcotic office, so that they can take a man along who is a specialist on narcotic matters. We have federal legislation dealing with opium and coca leaves. With this legislation we will make a drive on this traffic and make every effort to stamp it out, and it will not cost very much.

NARRATOR: Just, like, a trillion dollars over the years.

ANSLINGER: I say that advisedly because we have men throughout the country at the present time who are dealing with the narcotic problem. But the use of marijuana is increasing.

NARRATOR: Even back then they were escalating their enforcement efforts to no avail.

THOMPSON: I would like to know whether or not these marijuana cigarettes move through legitimate channels. Are there manufacturing concerns that make them, or are they rolled in the kitchens and cellars like illicit liquor used to be?

ANSLINGER: It is 100 percent illicit.

THOMPSON: What is the price of marijuana?

ANSLINGER: The addict pays anywhere from 10 to 25 cents per cigarette. It will be sold by the cigarette. In illicit traffic the bulk price would be around $20 a pound. Legitimately, the bulk is around $2 a pound.

THOMPSON: How does that compare with the price of opium or morphine? Do the class of people who use this drug use it because it is cheaper than the other kinds?

ANSLINGER: That is one reason, yes, sir. To be a morphine or heroin addict it would cost you from $5 to $8 a day to maintain your supply. But if you want to smoke a cigarette you pay 10 cents.

BOEHNE: Just one of them can knock the socks off of you?

ANSLINGER: One of them can do it.

McCORMACK: Some of those cigarettes are sold much cheaper than 10 cents, are they not? In other words it is a low-priced cigarette, and that is one of the reasons for the tremendous increase in its use?

NARRATOR: Marijuana was a poor person’s drug. And still would be if it weren’t for prohibition.

ANSLINGER: Yes. It is low enough in price for school children to buy it.

McCORMACK: And they have parties in different parts of the country that they call “Reefer parties?”

ANSLINGER: Yes, sir, we have heard of them, and know of them.

NARRATOR: But we have never been invited… And now we are getting our revenge.

FULLER: Another thing is that they will not be able to get other kinds of dope, but they do have an opportunity to get this marijuana, which causes it to be so much sought after and used in the community.

ANSLINGER: That is true, and the effect is just passed by word of mouth, and everybody wants to try it.

WOODRUFF: Have you put into the record a statement showing the names of the different states in which this drug plant is grown?

ANSLINGER: It is grown in practically all states… I have a statement showing the seizures of marijuana during the calendar year 1936 in the various states. (The PAGE brings it around.)

NARRATOR: This table showed that more than half the marijuana seized by law enforcement was in Mississippi and Louisiana. The quantities were very small, given how widespread cultivation is today. California ranked third in amount of marijuana seized —and the total was only 623 pounds. If the goal of prohibition was to reduce marijuana production in the United States, it has been a colossal failure.

ANSLINGER: I would also like to put into the record the statement of the district attorney that I referred to… And I want to introduce correspondence from the editor of a Colorado newspaper who was asked by civic leaders and law officers to contact the Treasury Department. Quote: Two weeks a go a sex-mad degenerate named Leo Fernandez brutally attacked a young Alamosa girl. He was convicted of assault with intent to rape and sentenced to 10 to 14 years in the state penitentiary… I wish I could show you what a small marijuana cigarette can do to one of our degenerate Spanish-speaking residents. That’s why our problem is so great; the greatest percentage of our population is composed of Spanish-speaking persons, most of whom are low mentally, because of social and racial conditions. End quote.

DOUGHTON: Mr. Anslinger, at this time the committee would like to thank you for your time and call another witness before our adjournment today. I will, however, ask for you to be available to this committee for any further testimony during the remainder of hearings on this matter.

Act Two

NARRATOR: Wednesday, April 28. Act two, scene one. “The Expert Witnesses.” Protocol calls for substantive testimony in support of Congrressional legislation. The sponsor of the prohibition bill, the Treasury Department, is supposed to produce evidence that documents the nature and extent of the problem. How will they back up Harry Anslinger’s claims? Why, exactly, is a federal prohibition of marijuana necessary?

CULLEN: The committee will come to order. Yesterday when the committee adjourned we had heard several witnesses in favor of the pending bill, HR6385. Are there any more witnesses to be heard in favor of the bill?

HESTER: We have three more witnesses, Mr. Chairman.

CULLEN: We shall be glad to hear them this morning.

NARRATOR: But first, a first note of concern.

CULLEN: I have in my hand a letter addressed to the chairman of the committee from the Armstrong Cork Products Co., which suggests an amendment to the bill. I will ask the clerk to read the letter, which will be inserted in the record. (Below is a photo of the factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Armstrong manufactured linoleum. Now it’s live-work lofts.)

CLERK: The undersigned company, one of the principal manufacturers of linoleum in the United States has consumed substantial quantities of hempseed oil in the past, in the manufacture of hard-surface floor coverings. At present none of this oil is being used by us, but conditions in the drying-oil market may change in the future and again find us among the ranks of consumers.We are in thorough sympathy with the object which is sought to be accomplished by HR6385 —to control the growing traffic in marijuana.

We believe, however, that the definition of “marijuana” contained in section 1(b) is needlessly too broad. We suggest at the end of line 6, page 2, the period should be changed to a semicolon and the words “and provided further, shall not include the oil derived from the seeds” be added to this paragraph. Hempseed oil, so far as we have been able to discover, presents no dangers in connection with the control of marijuana. It should therefore be excluded from the bill.

For the Armstrong Cork company, Jesse R. Smith.

NARRATOR: The Treasury Deparment lawyer Clinton Hester then read a long, complicated “summary of the effect of the marijuana bill upon legitimate industry.” Doctors, druggists and some industrial users would be exempt from the sales tax, but not the excise tax and the paperwork on every transaction. And the birdseed distributors would not even be exempt from the sales tax.

HESTER: Since marijuana bird seed contains the drug and is capable of being used by human beings for smoking purposes and since, if negligently disposed of, it propagates new marijuana very rapidly, all occupational and transfer taxes imposed by the bill are applicable with respect to bird seed containing marijuana. Since the ultimate purchaser of bird seed could not register under the bill, a transfer to him would be subject to the prohibitive $100 tax. Thus, the effect of the bill is to prevent the use of marijuana seed in bird seed.

NARRATOR: So the birdseed producers were to be totally shafted —not to mention the canaries, who used to sing all over America.

CULLEN: Who is your next witness, Mr. Hester?

HESTER: I would like the committee now to hear Dr. Munch, a pharmacologist from Temple University, Philadelphia.

NARRATOR: Doctor James Munch had been the director of research for Sharp and Dohme, and was now in charge of tests and standards for another major pharmaceutical company, John Wyeth & Bros. Munch started off with an explanation of how dogs are used in drug development. The graphic is of a test dog employed by Parke, Davis & Co. It’s from a brochure the company published in the 1920s to promote Cannabis Americana —as opposed to Cannabis Indica.

MUNCH: We have to give larger doses as the animals are used over a period of six months or a year. This means that the animal is becoming habituated, and finally the animal must be discarded because it is no longer serviceable.

McCORMACK (impatient): We are more concerned with human beings than with animals. We would like to have whatever evidence you have as to the conditions existing in the country, as to what the effect is upon human beings. Not that we are not concerned about the animals, but the important matter before us concerns the use of this drug by human beings.

MUNCH: I was making the point to show that in 1910 and in 1920 the Pharmacopoeia accepted cannabis as one drug for use in human medicine, and that that is the method of standardization, because there was no other method by which this could be standardized. When we considered the material for the Pharmacopoeia in 1930, we found that this method of standardization was not useful. We found that the International committee on Standardization of Drugs of the League of Nations had not admitted cannabis because it is not used through the world. Therefore, that method of standardization was discarded, and so at this time the product which may be used is used without being standardized. But the use of it is definitely decreasing, as shown by production statistics and surveys of prescription ingredients.

REED: You say the use is receding?

MUNCH: It is disappearing; that is, its use in human medicine is decreasing.

REED: You do not wish us to infer that it is decreasing in use as a narcotic, do you?

MUNCH: Not at all. I am discussing the medicinal use.

VINSON: For what was it used?

MUNCH: I can only give you the literature. No physician with whom I am immediately acquainted uses it at this time. In the early days it was used in cases of sleeplessness and to make your last moments on earth less painful when you were dying from rabies. There may be other uses, but I have not found them.

VINSON: As I understand you, the use of marijuana was to ease the last hours of a person in distress from excruciating pain.

MUNCH: Yes, sir.

VINSON: I feel certain there are many substitutes that could have been used before and be used now for the purpose of which marijuana to some extent was used.

NARRATOR: Thank you, Doctor Vinson.

MUNCH: Yes, that is true. Most of the modern drugs for the annulment of pain have been developed since about 1880 or 1890.

McCORMACK: Doctor Munch, have you experimented with any animals whose reaction to this drug would be similar to that of human beings?

MUNCH: The reason we use dogs is because the reaction of dogs to this drug closely resembles the reaction of human beings.

NARRATOR: Just about every veterinarian in Northern California has had to reassure an owner whose dog ODed on marijuana that the lethargic animal would eventually rise from its torpor and be just fine.

McCORMACK: And the continued use of it, as you have observed the reaction on dogs, has resulted in the disintegration of personality?

MUNCH: Yes. So far as I can tell, not being a dog psychologist, the effects will develop in from three months to a year.

NARRATOR: Makes you wonder what symptoms they were looking for. Not being a dog psychologist.

McCORMACK: I understand this drug came in from, or was originally grown in Asia.

MUNCH: Marijuana is the name for cannabis in the Mexican Pharmacopeia. It was originally grown in Asia.

McCORMACK: That was way back in the Oriental days. The word assassin is derived from an Oriental word or name by which the drug was called; is not that true?

MUNCH: That is my understanding.

NARRATOR: Exit Doctor Munch. The next witness in support of the bill was Herbert Wollner, a consulting chemist with the Treasury Department. He showed some slides and described how to make what is now known as “hash oil.”

WOLLNER: (Shows diagram of flowering top) Those are the flowering tops and the plant is covered with a tremendous number of very fine hairs. You will notice that at the base of these hairs there are little pockets, like apertures, where little sacks of resin are located. This resin contains an ingredient which the chemical technologist refers to as cannabinone or cannabinol. This material contains the active principle which does the job.

NARRATOR: The Congressional Record did not identify the graphics being cited. Wollner’s testimony is incorrect, given what we know now. The “very fine hairs” Wollner described emerging from “little pockets” evidently refer to the styles and ovaries that comprise the pistils of female flowers. In the above drawing by the botanical illustrator Eugen Kohler, a pistil is enlarged at lower right. Each Cannabis female flower has a single pistil, comprised of two stigmas (the style) and an ovule (the prospective seed). The resin containing cannabinoids and terpenoids is secreted by glandular trichomes —tiny stalks topped by globular glands that emerge abundantly to cover the bracts that enclose and protect the ovule. Resin glands are also prominent on the small “bud leaves” that intersperse the female flowers.

VINSON: They use the whole thing?

WOLLNER: Yes. In the laboratory we extract this resin and then identify it… The identification problems have been worked out very clearly from the botanical and from the purely laboratory approach, and that is in such shape right now that the transmission of that information to police officers throughout the country would be perfectly possible.

This close-up of Cannabis flowers (below) shows the styles (Wollner’s “very fine hairs”) emerging from ovules (Wollner’s “little pockets”). The little white structures on the bracts and bud leaves are glandular trichomes.

VINSON: How do they get this into commercial use? I am talking about the flowering plant. Do they have to take it in its natural state?

WOLLNER: There are a variety of ways. In the early days, when they used hashish, they would jounce the flowering tops up and down in bags and then the resin would collect on the surface of the cloth and was scraped off and mixed with sweets and eaten. At the present time in reefers and muggles there is no separation. They smoke the stuff in toto, the leaves, the flowering tops, and everything.

CROWTHER: Is that the oil that the manufacturers used to produce in considerable quantities?

WOLLNER: That is a different oil. That oil derives from the seed of a marijuana plant. The seed of the plant contains a drying oil which is in a general way similar to that of linseed. Those seeds contain a small amount of that resin, apparently on their outer surface according to quite a number of investigators.

NARRATOR: Wollner is trying to explain the difference between hempseed oil and what we now call hash oil. The question of how much trace THC can be found on the seeds’ surface is raised today by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration —the successor to Anslinger’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics— to block importation of hemp seed from Canada.

BUCK: Does the oil from the seed contain any of this deleterious matter?

WOLLNER: That would in a large measure depend upon the condition of the seed and the condition of manufacture, but I would say in any event the oil would not contain a large amount of this resin.

BUCK: Would it be enough to have any harmful effect on anyone if taken internally?

WOLLNER: I would say no; it would not contain such an amount.

FULLER: As I understand, you say the oil does not contain much if any of the drug?

WOLLNER: It does contain some of the drug, but not much. It would appear, offhand, to be rather difficult to separate, but processes might possibly be developed for that purpose.

FULLER: So the oil would not be useful for the purpose for which they are using this marijuana.

WOLLNER: No.

FULLER: So, far as the oil from the seed is concerned, it is harmless, as far as human use is concerned?

WOLLNER: That is right.

CULLEN: We thank you for your statement.

NARRATOR: The Congressional Record did not identify the graphics being cited. Wollner’s testimony is incorrect, given what we know now. The “very fine hairs” Wollner described emerging from “little pockets” evidently refer to the styles and ovaries that comprise the pistils of female flowers. In the above drawing by the botanical illustrator Eugen Kohler, a pistil is enlarged at lower right. Each Cannabis female flower has a single pistil, comprised of two stigmas (the style) and an ovule (the prospective seed). The resin containing cannabinoids and terpenoids is secreted by glandular trichomes —tiny stalks topped by globular glands that emerge abundantly to cover the bracts that enclose and protect the ovule. Resin glands are also prominent on the small “bud leaves” that intersperse the female flowers.

This close-up of Cannabis flowers (below) shows the styles (Wollner’s “very fine hairs”) emerging from ovules (Wollner’s “little pockets”). The little white structures on the bracts and bud leaves are glandular trichomes.

And here are the glandular trichomes —the globular objects atop the green stalks— in a beautiful electron micrograph (below) made at an electron microscopy facility run by Dr. Klaus Adler of IPK-Gatrsleben, a German institute for plant breeding. A country girl studied the ruffles on the stalks and said, “A lot like the ruffles on a Barred Rock chicken.” When something works, nature makes use of it in various contexts.

Mr. Hester, who is your next witness?

HESTER: Our final witness is Lyster H. Dewey. He is a botanist, and while he is now in retirement, officials of the Department of Agriculture have referred us to him as the foremost expert on the botanical aspect of this plant.

DEWEY: My name is Lyster H. Dewey. Mr. Chairman. When I was in the Department of Agriculture I was in charge of fibers other than cotton from 1898 to 1935, when I was retired for age. The plant cannabis sativa, so-called by Linnaeus in 1753, constitutes one species of hemp that has been known longer than any other fiber plant in the world. It was cultivated in China at least three centuries before Christ.

COOPER: Did I understand you to say that you had charge of fibers?

DEWEY: The cultivation of fiber plants —flax, hemp, jute and all other fiber plants except cotton… The term hemp is better known than marijuana because the name marijuana has been used only for the drug, while hemp is used in connection with the production of fiber. Hemp has been grown in nearly all countries in the north temperate zone, and to some extent in the south.

DINGELL: What kind of fiber is marijuana hemp, or the plant we have under discussion? What is it used for?

DEWEY: It is used for commercial twines, such as bookbinder’s twine, hatters twine for sewing hats, and it was formerly used for what was called express twine, or heavy twine.

DINGELL: In other words lightweight twines are being made from the hemp that we have under discussion here today?

DEWEY: Yes sir. The fiber is used for commercial twine.

McCORMACK: To what extent?

DEWEY: In this past year, in this country, there were about 7,000 acres grown, or more than that. Nearly 10,000 acres. The largest areas are in Wisconsin and Illinois —especially around Danville in Illinois. It is also grown in Kentucky; in northeastern Nebraska, in Cedar County, and in southern Minnesota. There it is chiefly grown around Blue Earth and Makato. It is grown in Wisconsin around Beaver Dam, Juneau, and Brandon, north of Waupun.

DINGELL: Are those the only states where it is commercially grown?

DEWEY: Yes, sir. It has been grown in other states, and efforts are being made to grow it in other states for fiber purpose.

McCORMACK: Isn’t it also used for birdseed?

DEWEY: Yes, sir; it is used for birdseed; but most of the birdseed is imported.

NARRATOR: The Treasury Department then brought in a Washington D.C. veteranarian named Buckingham as an extra witness in support of the bill.

BUCKINGHAM: …If you are practicing veterinary medicine you would find that there were better drugs for the purpose. For instance, they could use morphine or atropine hypodermically with better results.

VINSON: So you think it is a harmful drug, and that your profession in the District should be recorded in support of this measure?

BUCKINGHAM: That is right. Perhaps my thought on the subject has been accentuated because of the fact that I attend at the Lorton Pentientiary, as well as at the reformatory, and I understand that this drug is mainly used by that type of gentlemen who climb in second story windows, break into banks, and so forth.

VINSON: And it reaches children in schools, also.

BUCKINGHAM: Yes, sir.

FULLER: Therefore you are not only opposed to the use of this drug here, but you would eliminate it by regulations not only here, but all over the United States.

BUCKINGHAM: Yes.

NARRATOR And so ended the parade of witnesses called by the Treasury Department in support of marijuana prohibition. Act two, scene two: “The Befuddled Hempsters.” Comes now the Honorable Ralph F. Lozier, a former judge and Congressman, retired to private practice.

LOZIER: For the record and for the information of those present who do not know me, I will say I am Ralph F. Lozier. My home is in Carrollton, Missouri, where I have for many years been engaged in the practice of law. I appear before this committee as general counsel for the National Institute of Oilseed Products, an association of about 20 concerns dealing in and crushing vegetable oil-bearing seed. I have a list of the organizations composing this association, and will hand it to the reporter for the purpose of the record.

NARRATOR: The National Institute of Oilseed Producers consisted mainly of California companies that imported the seed by boat from China: Pacific Vegetable Oil Corporationl, RJ Ruesling & Co, CB Jennings & Co, SL Jones & Co., El Dorado Oil Works; Durkee Famous Foods, Inc., Berkeley Oil & Meal Co., Western Vegetable Oil, Snow Brokerage, California Flax Seeds Products, Copra Oil & Meal, Pacific Nut Oil, Globe Grain & Milling, California Cotton Oil, Producers Cotton Oil of Fresno. And Spencer Kellogg & sons, with six offices, from Buffalo, New York to Duluth, Minnesota. These were substantial businesses that did not want to see their operations disrupted by a prohibition bill.

LOZIER: The measure before you is one which should not be hastily considered or hastily acted upon. It is of that type of legislation which conceals within its four corners activities, agencies and results that this committee, without a thorough investigation, would never think were embodied in its measure.

NARRATOR: How prophetic! Unfortunately, Mr. Lozier is about to undermine his own point.

LOZIER: I want it distinctly understood that the organizations for which I speak want to go on record as favoring absolutely and unconditionally that portion of this bill which seeks to limit and the use of marijuana as a drug, or for any other injurious purpose. That portion of the bill, it seems to me, can merit the opposition of no right-thinking or right-acting man. I agree with the witnesses for the government that the use of the drug marijuana is a vicious habit that should be suppressed.

NARRATOR: The businessmen who used hemp endorsed the goal of marijuana prohibition without questioning its scientific validity —even though they were the ones who had some knowledge of the plant and should have known that the so-called dangers were being vastly exaggerated by the government. They evidently thought that seeking an exemption for themselves was a better tactic than challenging the rationale for prohibition. This is a form of opportunism: “goody-goodyism.” Goody-goodyism prevails to this day among many hemp and medical-marijuana advocates.

LOZIER We do know that the deleterious principle, element or radical which is the base of this drug is not to be found in the seed or oil, but in the flowering tops of the female plants, or in the resins therefrom. Every country has a little different name for marijuana. Respectable authorities tell us that in the Orient, at least 200 million people use this drug; and when we take into consideration that for hundreds, yes, thousands of years, practically that number of people have been using this drug, it is significant that in Asia and elsewhere in the Orient, where poverty stalks abroad on every hand and where they draw on all the plant resources which a bountiful nature has given that domain —it is a significant fact that none of those 200 million people has ever, since the dawn of civilization, been found using the seed of this plant or using the oil as a drug. Now, if there were any deleterious properties or principles in the seed or oil, it is reasonable to suppose that these Orientals who have been reaching out in their poverty for something that would satisfy their morbid appetite, would have discovered it; and the mere fact that for more than two thousand years the Orientals have found this drug only in flowering tops of the female plants and not in the seeds and oils, affords convincing proof that the drug principle does not exist in the plant except in the flowering tops.

The seed of cannabis sativa is also used in a part of Russia as food. It is grown in their fields and used as oatmeal. Millions of people every day are using hemp seed in the Orient as food. They have been doing that for many generations, especially in periods of famines. But the authorities say that the narcotic principle is absolutely absent from the seed and absent from the oil in this plant.

FULLER: I do not think that the gentlemen who have presented the case on behalf of the committee, or the Government have claimed that it was present in the oil.

LOZIER: They have said it was in the seed.

FULLER: He said there was very little in the seed. He said there would be no injurious effect from the little there was in the seed.

LOZIER: The point I make is this: that this bill is too all-inclusive. This bill is a world-encircling measure. This bill brings the activities of this great industry under the supervision of a bureau, which may mean its suppression.

NARRATOR: Lozier was right. Within a few years the Treasury Department would push for a more complete ban on hempseed oil.

LOZIER: In the last three years there have been 193 million pounds of hemp seed imported into this country, an average of 64 million pounds a year. In addition, 752,000 pounds of hemp oil have been imported.

WOODRUFF: What is the oil used for?

LOZIER: It is a rapidly drying oil to use in paints. It is also used in soap and linoleum.

COOPER: Just what do you object to in this bill?

LOZIER: This bill brings the crushers and importers of hempseed under its provisions and requires not only a license fee, which is nominal, but it provides for government supervision and it provides for reports.

DINGELL: How could you control the drug aspect of it without a reasonable and proper regulation of the entire industry? You will grant that in order to produce the seed and oil, you must permit the growth of the marijuana plant.

LOZIER: Not in this country. Nearly all of the seeds come from the Orient. The point I make is that if you turn all of the hempseed grown in this country over to the persons who have the marijuana habit, they would not be able to satisfy that habit. The point I make is that it is not necessary.

VINSON: Mr. Lozier, we know you, we love you, and we respect your ability as an advocate. Suppose you put your finger on the language in the bill that would bring about the supervision to which you object.

LOZIER: I am objecting to first, the supervision.

VINSON: The supervision of what?

LOZIER: Of the industry! By requiring reports and by a system of espionage!

VINSON: Where is that in the bill?

LOZIER: They are required to make reports. The books of the seed crushers would be subject to inspection. Under this bill the Government has a right to go into the factories and offices and make investigations.

VINSON: It seems to me that you are so certain that the activities of your people are not connected, directly or indirectly, with the use of this marijuana as a drug, that you would not hesitate to permit an investigation in order to kill this traffic.

NARRATOR: By granting that marijuana is a dangerous drug, Lozier opened himself up for this thrust by Congressman Vinson of Kentucky.

VINSON: I know that your people are not knowingly a part or parcel of the traffic. I know that from what you say. If that is not the case, of course, they ought to come under the law, and if that is the case, they will not be hurt.

LOZIER: I will answer that in this way: that there is no more reason for the supervision of the hempseed crushing industry under this bill than there is for the supervision of the rye, wheat, or other grain from which alcohol may be extracted.

VINSON: Cannot marijuana be grown from seeds that come into the possession of your crushers?

LOZIER: Yes, sir; it might be, but the germination of those seeds is practically nil.

VINSON: But you admit that this plant can be grown from seed coming into the possession of your people, and that being true, do you not think it proper to provide for the exercise of the government’s function to do that which will prevent the further propagation of this plant in this country?

LOZIER: These people buy these cargoes. They buy this product by shiploads, by trainloads, and by carload. They manufacture this oil and sell it in tank cars. They have been engaged in this business for years, and never, until the last three weeks, was any suggestion made that they were handling a commodity that was carrying a deleterious principle that was contributing to the delinquency of the people of the United States!

NARRATOR: Right on, counselor. Too bad you conceded that the plant contains a “deleterious principle.”

VINSON: Perhaps the committee in a way might be subjected to criticism for not acting on the matter before. But it is fair to state it was not called to our attention. If you admit that this marijuana is a menace to the youth as well as to the adult citizenship of this country, do you not recognize the power of the federal government to operate upon that drug?

LOZIER: Yes.

VINSON: If you recognize that, do you not also recognize in the Government the power and the right to prevent the illicit growth of that plant?

LOZIER: I am objecting to the method.

VINSON: You do not recognize the power of Congress to do that?

LOZIER: Yes, the government has that absolute power, but the question is whether or not the government should exercise it in this way.

VINSON: I think that your people ought to hasten to join hands with the federal government to prevent the condition obtaining in this country that my good friend has depicted as existing in the Oriental countries.

CULLEN: If you will suspend a moment, the House is now in session and will be taking up a matter in which many members are interested. I am wondering if we should not adjourn at this point to meet again tomorrow morning.

LOZIER If you will allow me one moment before adjournment, I will call your attention to paragraph 6, page 9, which is an exception that permits the crusher to sell marijuana to the manufacturer or compounder for use by the vendee as a material in the manufacture of, or to be prepared by him as a component of, paint or varnish. Now under that provision you could not sell the cake or meal to farmers or the oil to makers of soap or linoleum.

CULLEN: (ignoring him) The committee will now stand adjourned until 10:30 tomorrow morning, at which time we will continue hearing the testimony of the witnesses in opposition to the bill.

NARRATOR: Thursday April 29th. A brief session

DOUGHTON: The committee will be in order. This is a continuation of the hearing on the bill HR 6385. After the adjournment yesterday I suggested to Mr., Hester, who has been representing the Treasury Department in the presentation of this bill, that he have a conference with some of those who have appeared in opposition to certain provisions of the bill to see if it were possible to iron out the differences and reach an agreement. Do you have something to report, Mr. Hester?

HESTER: Yes, Mr. Chairman, I have, and as a result of our conference, those gentlemen who represent importers of the seeds and those who crush the seeds for the purpose of making oil and using the residue of the seeds for making meal and cake, have expressed the view that they are willing to pay the occupational tax which is provided in this bill if the definition of marijuana is amended as to eliminate oil made from the seeds, and the meal and cake which are made from the seeds, as well as any compounds or manufactures of either oil, meal, or cake.

The also take the position that under the bill as now drawn, they could not sell this residue from the seeds, or the meal and cake, to cattlemen, because the cattlemen could not register under the bill, and that therefore they would have to pay a prohibitive tax.

I will say this: that I have never come up here in connection with any legislation where the Way and Means Committee has not found it necessary to make some changes. We always expect that when we come before the Ways and Means Committee, because of the fine consideration the committee gives to all legislation. If the committee should ask the Secretary of the Treasury for his recommendation with respect to the proposals made by these gentlemen representing this legitimate industry, I will say very frankly to the Secretary that I see no objection to amending the definition of marijuana so as to eliminate oil, meal, cake, and the manufactured compounds of those materials.

NARRATOR: The next witness was introduced prior to adjournment

SCARLETT: Mr. Chairman, my name is Raymond G. Scarlett, representing William G. Scarlett & company, seed merchants of Baltimore. We represent the interest of the feed manufacturers on this subject, which is a little different angle from that which has been presented heretofore. We would like to be heard at some time.

DOUGHTON: We will ask you to be here tomorrow morning.

SCARLETT: I will be present.

NARRATOR: Friday, April 30.

SCARLETT: Mr. Chairman, I might say there are only two representatives of the seed industry here today, because it so happens that our trade association, which represents 90 percent of the seed dealers in the country, is now in session in Chicago, and one of the things in which they are engaged is the drafting of suggests for provisions for the Federal regulation of seed, and our counsel could not be here for that reason.

We handle a considerable quantity of hempseed annually for use in pigeon feeds. That is a necessary ingredient in pigeon feed because it contains an oil substance that is a valuable ingredient of pigeon feed, and we have not been able to find any seed that will take its place. If you substitute anything for the hemp, it has a tendency to change the character of the squabs produced; and if we were deprived of the use of hempseed, it would affect all of the pigeon producers in the United States, of which there are upwards of 40,000.

DOUGHTON: Does that seed have the same effect on pigeons as the drug has on individuals?

SCARLETT: I have never noticed it. It has a tendency to bring back the feathers and improve the birds.

NARRATOR: Too bad that Mr. Scarlett didn’t point out the implications of his own knowledge. Hempseed oil contains some unique component or components very beneficial to birds. The witness could have cited the canary in the coal mine in reverse —not dying for lack of oxygen, but singing in the pursuit of love, and with feathers gleaming. But he took a different tack.

SCARLETT: We are not interested in spreading marijuana, or anything like that. We do not want to be drug peddlers. But it has occurred to us that if we could sterilize the seed there would be no possibility of the plant being produced from the seeds that the pigeons might throw on the ground.

DOUGHTON: If you were allowed to use this seed for that purpose, and it was sterilized, would that eliminate your objections?

SCARLETT: Yes, sir, that is the agreement we have reached with the Treasury representatives. There has been an amendment proposed to section 1(b) by excluding from the definition of marijuana sterilized seed which is incapable of germination.

DOUGHTON: Suppose it should develop that in your efforts to sterilize the seed you should not be successful… Then would you object to legislation necessary to protect the people from the deleterious effects of this drug?

SCARLETT: No, sir. But sterilization could be very easily accomplished.

DISNEY: What is the relation between hempseed and marijuana?

SCARLETT: Until Monday of this week we did not know that there was any connection between the two. When this bill came and we saw that it was called a bill to impose an occupational excise tax upon dealers in marijuana, we paid no attention to it. Nobody in the seed trade refers to hempseed as marijuana. Hempseed is a harmless ingredient used for many years in the seed trade. They say that hemp and marijuana are one and the same thing, but it was not until Monday that we knew they were.

DISNEY: That is as far as the trade is concerned?

SCARLETT: Yes, sir. The trade at large do not know that this bill that is under consideration contains any provision affecting them, because the title of the bill would give them no knowledge that it was hempseed that was under discussion.

REED: I want to get it clearly in my mind that this marijuana and the ordinary hemp that we hear about are the same thing. The plant is the same?

SCARLETT: Yes, sir.

REED: There is no difference?

SCARLETT: No sir, not to my knowledge.

REED: Can anybody answer that question.

HESTER: That is right.

DISNEY: Do you mean field hemp?

REED: Yes. I am talking about field hemp. I want to get that clear.

DOUGHTON: Is not one a manufactured product and the other the substance from which it is made? The hempseed is the substance from which the marijuana is produced, is it not?

NARRATOR: Who came first, the seed or the plant?

SCARLET: No, sir. Marijuana is produced from the resin of the female flowers or blossoms.

DOUGHTON: It comes from the hempseed?

SCARLETT: Yes, sir, but in India when they produce marijuana, they are very careful to go through the fields and pick out the male plant so that they will not fertilize the female plant.

NARRATOR: And I thought “sinsemilla” was invented in Mendocino County in the 1970s!

DOUGHTON: If you had no hemp weed you would have no marijuana would you?

SCARLETT: That is correct. That is the reason I said we would sterilize the seed.

REED: Several people have talked to me about marijuana and they have impressed me with the fact that they are different plants. I think that ought to be cleared up in the public mind, so that we may know we are dealing with hemp. I suppose a good many people have the idea that it is some sort of a new species of plant in the country.

DISNEY: Down in our part of the country I understand marijuana grows everywhere, just as an ordinary weed. I would like to get a clear understanding on that.

REED: In other words, it is hemp growing wild, is it not?

DISNEY: I do not know.

REED: There seems to be quite a good deal of confusion about it, and the newspapers are publishing stories about it and we might as well clear up that situation and say that we are not dealing with the ordinary hemp plant, wild or cultivated, if that is right.

HESTER: That is right.

NARRATOR: Hester got in the last word, and it was not right. The same plant —“Cannabis,” as named by Linneaus— is known in America as “hemp” when bred for fiber and “marijuana” when bred for the drug content of its resin.

DOUGHTON: Is there anyone else who desires to be heard?

HERTZFELD: My name is Joseph B. Hertzfeld. I am manager of the feed department of the Philadelphia Seed Co. of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I want to say at the outset, Mr. Chairman, that our firm is heartily in sympathy with the aims and purposes of this bill, and we have no desire to become parties in spreading this drug around the country. We have been manufacturers of feeds and mixed birdseeds for many years, and in those mixtures hempseed is a very important item. Hempseed is very beneficial because it adds the proper oil to the mixture and promotes the growth of feathers, and it is also a general vitalizer.

NARRATOR: “A general vitalizer” for birds, and yet it kills people? Doesn’t anybody see the disconnect?

HERTZFELD Birds lose their feathers and hempseed aids considerably in restoring the bird’s vitality quickly. Otherwise there is a delay of two or three months before the bird gets back into condition, and the use of hempseed helps to accomplish that purpose.

I want to second what Mr. Scarlett has just said, and to express our willingness to have the seed sterilized so that it cannot be grown and thus cause any harm. This agreement which has been referred to, that we reached yesterday with Mr. Hester, is very satisfactory to us.

NARRATOR: You’re not getting off that easy.

CROWTHER: Would the sterilization prevent the germination remove such of the drug as exists in the hull or the outside cover of the seed?

HERTZFELD: I cannot answer that. We have seen evidence by eminent authorities that there is not any of the drug in the seed.

CROWTHER: Someone testified that there are some particles of the resin on the outside of shell of the seed.

HERTZFELD: (indicating exhibit) The type of seed that we use is this seed here. That is this brown seed dried and matured.

DOUGHTON: Is there any of the residue on that seed when it comes into your possession?

HERTZFELD: No, that is gone. When this seed is matured and dry we grind the shell off in the threshing operation. I had occasion to write to the Bureau of Plant Industry in the Department of Agriculture about this in 1935, and under date of October 4 I had a communication from FD Richey in which he said, “The female inflorescence of the plant possesses physiological properties that are the basis of abuse as a potent drug. The seed is considered to be devoid of such properties.” It has been used for various purposes for years, and I have never heard of any ill effects. On the contrary, it seems to be extremely beneficial.

NARRATOR: Is the momentum about to change?