The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 young men who changed Harvard forever By Kent Garrett with Jeanne Ellsworth, $27 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Kent Garrett has given a wonderful gift to his college classmates —a book about ourselves, focused on the Black members of our class and written in the clear, honest first-person. Garrett grew up in the projects in Brooklyn. His parents had moved north from Aiken, South Carolina, and they still returned there in the summers to work on the family farm. Kent’s father was an NYC subway motorman and on weekends ran a kitchen-floor-waxing business. (Kent helped out.) He went to Boys High and excelled. He applied to Harvard and got admitted. Cut to September ’59, driving up with his parents and sister, followed by three aunts and an uncle in another car to celebrate and share his success. By the time he first sets foot in The Yard and describes the architecture, I was seeing both Kent and his family arriving early in the day, and me and my father arriving in early evening.

This split-screen effect would recur as I read on, though the POV is specifically that of a black man. Garrett’s dorm-crew job cleaning bathrooms was a special indignity: “Of all the images I might have presented to my white classmates —many of whom have never seen a Negro in any other role than servant, let alone as a peer— this is the worst.” Given a paucity of Negro girls (there was only one, Connie McDougald, in Radcliffe’s class of ’63), Garrett and friends made their way to parties in Boston and Roxbury. Bobby Gibbs, in the closet on campus, found a vibrant gay scene across the river.

“Almost from the first day,” Garrett writes, “we Negroes started noticing each other, making mental note of who and where the brothers were.” The five who lived in Thayer South —Kent, Ezra Griffith, Fred Easter, Lowell Johnston and Jack Butler— sat together in the freshman union dining hall and “unintentionally became the Black Table, with a fluid membership not always limited to Negroes.” For Kent “it was something of a refuge, a ready made friendship group where I would be understood and liked. And there was something comforting about the rhythm and style of conversation at the Black Table… If one of the guys said ‘I’m fiittin’ to go study’ …nobody looked askance, and everybody understood you.”

Eighteen was three times as many Negroes as Harvard had been admitting to its freshman class. Garrett credits a prescient “affirmative action” policy introduced by Dean John Munro in 1958, and effective outreach by Fred Glimp’s Admissions Office to high schools across the U.S. The book takes its title from our classmates’ leading role in forming the African and Afro American Association of Students, which sought official recognition from Harvard in April ’63. The prime mover was Garrett’s closest friend, Jack Butler. (He died of cancer in 2011; The book is dedicated to him.)

Butler and Lowell Johnston were among those profoundly impressed by Malcolm X when he analyzed the plight of “so-called Negroes” at Sanders Theater in March, 1962. Garrett wonders why he didn’t attend that event. “Lowell and Jack were angry young men,” he reflects, “much more aware of racial politics than I was.” Butler subsequently arranged a dinner with Malcolm at Eliot House (Bill Strickland ’58 had a Roxbury connection to him). Garrett didn’t miss him this time. “I was inspired not only by Malcolm’s message,” he writes, “but by his sincerity and charisma, as well as energized by the pride, even arrogance, that was so tempered with humility. Was I transformed into a militant, enlightened race activist? No, but something shifted inside my young mind and soul.”

The AAAAS was deemed discriminatory by the Harvard Council on Undergraduate Affairs in May ’63 and denied official sanction because membership would be restricted to “African and Afro-American students currently enrolled in good standing at Harvard and Radcliffe.” After an appeal to the Faculty Committee on Student Activities was rejected in the fall of ’64, the AAAS changed its criterion for membership to “by invitation” —just like a Final Club— and got Harvard’s seal of approval and the funding that came with it.

After graduating Garrett spent a desultory year at NYU med school, then became a producer of TV commercials. In 1968 he put his know-how to use “on something that mattered” as a producer for the public TV show Black Journal. He then spent some ten years producing the news at CBS (with Dan Rather), ten at NBC (with Tom Brokaw), ten as a dairy farmer (with cows), and almost ten researching and writing The Last Negroes with Jeanne Ellsworth, his partner in life as well as on the book project. Tracking down the protagonists took them across the country by car and to Austria and the Virgin Islands. The pay-off is a sharing of some very interesting, intelligent perspectives.

“We chose our organization’s name not so much as a rejection of ‘Negro’ but as a step forward into the possibility and power that ‘Afro American’ seemed to embody,” Garrett writes towards the end. “There was no magic moment when all 18 of us said ‘Okay we’re not Negroes anymore.’ But in important ways we weren’t, through the accident of being alive in our times and through the influence of the many voices of the civil rights movement and African liberation.”

The Supernova Effect in History

What, you may be wondering, does Kent Garrett’s book have to do with the medical marijuana movement, the subject of this site’s reporting and analysis?

“The Last Negroes at Harvard” indirectly provides another example of the phenomenon we’ve described as a political “supernova effect,” whereby the appearance of progress —the expansion and advance of a movement— actually represents its cooling. As O’Shaughnessy’s readers know, a supernova occurred circa 1966, when millions of students and GIs began smoking marijuana. The conventional wisdom is that the “decriminalization” measures adopted by many states in the 1970s represented progress towards legalization, and that the progress ended when NORML outed the Carter Administration’s enlightened drug-policy adviser, Dr. Peter Bourne, as a user. The “decrim” legislation of the ’70s may have looked like progress, but actually represented the cooling of the ’60s supernova (mass civil disobedience).

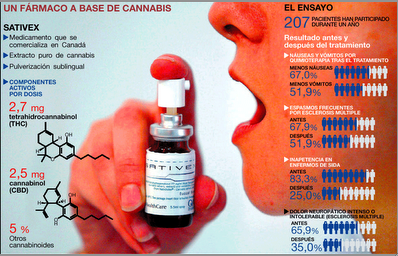

There was a concentrated supernova circa 1990 in San Francisco when AIDS patients en masse were using marijuana openly to bolster appetite (among other benefits). Dennis Peron opened the Cannabis Buyers Club to help meet their needs and Proposition 215 was drafted to provide legal protection for them. Reformers funded by George Soros and other enlightened billionaires then usurped the leadership and accepted the prohibitionists’ “narrow interpretation” of Prop 215. By 2016 they had replaced the radical medical marijuana paradigm with a “legalization” scheme acceptable to investors, bureaucrats, and law enforcement. There is a widespread impression that radical change was achieved. It wasn’t. Instead, cannabis was made safe for capital.

Readers of “The Last Negroes at Harvard” are reminded that in the early 1960s, many African nations seemed to be advancing beyond colonialist exploitation. That was the assumption of those of us who thought we were paying attention. But the supernova had ended in 1960 with the murder of Patrice Lumumba. All the subsequent progress was actually cooling.