The journal Epilepsy & Behavior has just published a special issue entitled “Cannabinoids and Epilepsy” that includes a groundbreaking paper by Drs. Dustin Sulak, Russell Saneto, and Bonni Goldstein, “The current status of artisanal cannabis for the treatment of epilepsy in the United States.”

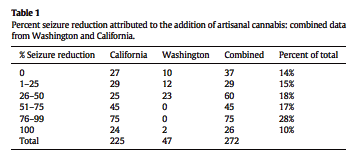

Goldstein based her report on 225 patients with intractable seizures seen at her practice in the Los Angeles area. Saneto reported on 47 patients seen at Seattle Children’s Hospital. Sulak, who is based in Maine, contributed four detailed case studies. They aggregated their results:

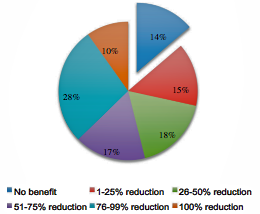

“Of 272 combined patients from Washington State and California, 37 (14%) found cannabis ineffective at reducing seizures, 29 (15%) experienced a 1–25% reduction in seizures, 60 (18%) experienced a 26–50% reduction in seizures, 45 (17%) experienced a 51–75% reduction in seizures, 75 (28%) experienced a 76–99% reduction in seizures, and 26 (10%) experienced a complete clinical response. Overall, adverse effects were mild and infrequent, and beneficial side effects such as increased alertness were reported. The majority of patients used cannabidiol (CBD)-enriched artisanal formulas, some with the addition of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA).”

Most newsworthy is the fact that a peer-reviewed publication has acknowledged the validity of data compiled by cannabis clinicians. Goldstein and Sulak are each identified as running “a private cannabinoid medicine practice.” Kudos to the editors at Epilepsy & Behavior who recognized their findings as worthy of inclusion in their journal! Henceforth the paper by Sulak et al will have to be acknowledged as evidence when the efficacy of cannabis in the treatment of epilepsy is assessed.

In January the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NAS) released a 400-page report evaluating the “strength of the evidence” regarding the health benefits and risks of cannabis as medicine. By far the strongest evidence, from the NAS experts’ perspective, were randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials (RCTs). The findings and observations of physicians who monitor cannabis use by patients —clinical evidence— was ignored completely, as we noted here. It wasn’t even dissed as “low quality!”

But from now on, when medical-establishment experts review the evidence on cannabis as a treatment for epilepsy, the paper by Sulak et al cannot be overlooked. It’s part of “the literature.”

Because the authors are cannabinoid-medicine specialists who care for their patients in ways that go beyond seizure reduction, their paper provides extremely important information not typically found in medical journal articles. Consider the following dense, poignant paragraph listing the “non-medical risks” that physicians must bear in mind when recommending a trial of cannabis to the parents of epileptic children:

“Availability of a consistent supply of the medication is frequently interrupted due to horticultural, manufacturing, and economic factors. Current market prices for artisanal cannabis preparations observed in Maine, California, and online range from 5 to 50 cents per milligram. Higher dosing ranges are financially unfeasible for many patients unless they grow and produce their own medicine, a complex process that presents many potential interruptions in treatment. Sudden loss of access to cannabinoids may result in rebound seizures. Hospital admissions present challenges, and patients or their guardians often must choose between interrupting cannabis treatment and violating hospital policies that forbid self-administration of medications, especially those with Schedule I status. In one of the sites (RPS), the hospital has families sign a waiver and allows them to administer home dosing of product, but does not provide storage. The potential for disruption of medical treatment or family structure related to child protective services and other legal agencies, even when the patient and medical provider operate within state laws, must also be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis.”

Sulak et al’s bottom line:

“Overall, the safety profile of quality-controlled herbal cannabis preparations is likely equal or superior to most Anti-Epileptic Drugs… Herbal cannabis has remarkably low toxicity, even at high doses, and no lethal dose of cannabis has been described. Conversely, the morbidity of AEDs are the most common impediment to achieving full effective dosing due to multiple types of toxicity ranging from tiredness to memory problems and even death.”

Washington state results:

We asked Sulak about his case report involving a 10-year-old boy who was started on a THCA-rich extract. Why THCA instead of CBD?

Sulak replied that THCA is often easier to come by. Plus:

“When people respond to THCA they usually respond at a much lower dose than they do to CBD. As a result, the trial takes less time. When you start someone on low-dose CBD it can take several months to work them up to the effective dose. With THCA it seems to go much faster, and of course a lower dose is more affordable for the families. So in many cases I’m starting with THCA —especially when the problem only involves seizures. If there are cognitive or behavioral issues, pain, spasticity, or other symptoms, I start with CBD or THC.”

Sulak et al acceptingly cite a paper reporting that a placebo effect influences the claim that cannabis reduces seizures. I have heard parents of epileptic children scoff —and have scoffed myself— at the notion of such a placebo effect. Sulak said it’s probably real in some instances, a function of the parents’ desperate hope for progress.

“A mother told me this week her daughter’s seizures were doing much better, down to three-four seizures per week. I looked at my notes from three months earlier and it was three to five seizures per week. While I believe that she may be doing much better in some global sense, and I have a tendency in general to believe my patients statements as a valid truth, if not a scientific finding, I don’t think all reports of seizure improvement are always accurate.”

ECB blood serum levels

It was surprising to read in Russell Saneto’s report on 47 patients from Washington State, “We are able to validate the product our patients are taking by serum analysis of drug levels.”

Testing blood-serum cannabinoid levels is not being done by California doctors or patients. Sulak explained that Saneto had been involved in the clinical trial at Seattle Children’s Hospital of Epidiolex, and that a lab in Pennsylvania had developed a panel to measure (certain) cannabinoid levels. Sulak hopes to get his patients access to a lab that can measure cannabinoid levels in the blood.

I think testing for endocannabinoid levels is going to be bigger than 23 & Me. Not just physicians and patients will want the data. Everyone will want to know their ECB tone! If your numbers are low you can justify your heavy reliance on exogenous cannabinoids. If they’re high you can say, “No wonder I’m so mellow!” An individual’s ECB levels probably change significantly over the course of a week, based on mood, etc., but I don’t think that will deter the average pot partisan with $99 to spare.