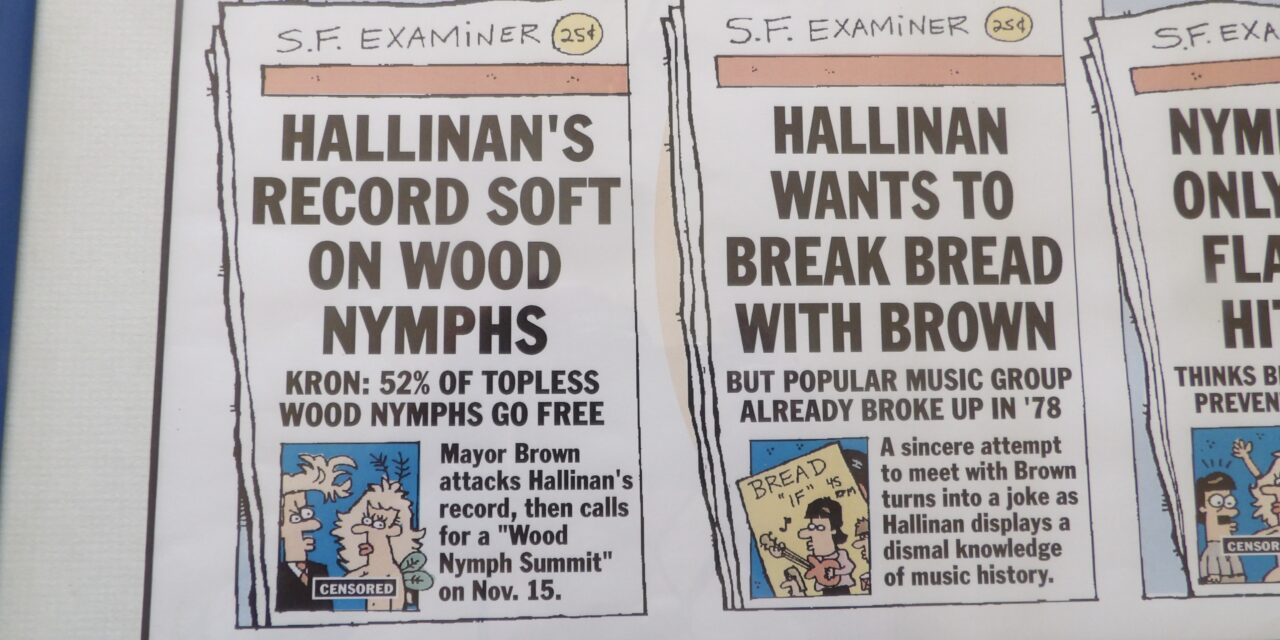

Terence Hallinan was always a bit mystified by Willie Brown’s animosity. Reading a headline in the Chronicle like “Brown excoriates Hallinan, other big-mouth critics,” he would shake his head in sad disbelief. When he said of the mayor, “He’s using me as a scapegoat, politically,” it was almost as if they might still be friends, personally. When Brown cut the District Attorney’s budget, Hallinan told reporters he thought there had been a misunderstanding that could be resolved if he and the mayor could “break bread” together.

“District Attorney Terence Hallinan is a ‘son of a bitch (who) should have been recalled,’ and the other ‘bigmouths’ who have been critical of the city’s homeless policy and dirty streets ought to shut up and do something other than make noise —so says Mayor Willie Brown in a biting interview with the San Francisco Neighborhood Newspaper Association.

“On Hallinan’s lack of prosecutions for people urinating, defecating and drinking on city streets: ‘That son of a bitch should have been recalled by the very people who are currently outraged. I’m more disgusted than you’ll ever believe.’

“On his critics: ‘I sometimes wonder where the hell they were when (former Supervisor) Amos Brown was taking all the heat for my proposal to snatch the cars of dope dealers who contribute to people (being) on the street…”

“The meeting of city department heads, that was quintessentially Willie. To assemble all these people —all of these critics of Terence— in a room. You mentioned the public defender, Jeff Brown. He hated us for no reason. He said he was progressive and we were progressives. Why would he hate us? He hated us because we were more progressive than him. He couldn’t solve any crime problems. And when Terence emphasized diversion, it affected his acquittal rate and made it look like he wasn’t getting people off anymore.

“Jeff Brown was anomalously against every program like drug court and prostitution court. He did an interview, I forget where, lambasting Terence and everything he did in his first year. There were plenty of supposed liberals who were doing that and they were all against him. It was sort of amazing that he got elected two times, I know how embattled Terence was, constantly. He was hated and reviled by the whole city bureaucracy, by basically everybody but the voters.”

Millstein asked, in conclusion, “Did Willie really say anything or do anything or direct anything besides call the meeting of department heads?”

Yes, I said, Willie did. He invited KRON’s Vic Lee to City Hall and let a cameraman get some long shots of the assembled bureaucrats seated around his magnificent conference table. And immediately after the meeting he gave Lee an exclusive interview in which he denounced the district attorney. He had run the ‘Recall Hallinan’ idea up the flagpole, as they used to say, hoping that people would salute. Not enough did.

Jerry Brown Keeps Hangin’ Round

The New York Times welcomed the new president oddly on Sunday January 24 with a piece called “What Jerry Brown Could Teach Joe Biden.” An odd accompanying graphic showed Jerry Brown himself seeking guidance from The Great Consultant on high. (California’s former governor is a first cousin of Jeff Brown, the Hallinan hater mentioned above.)

Journalist Shane Goldmacher attributes Brown’s election in 2010 to a savvy campaign strategy that involved avoiding over-exposure: “He let Meg Whitman, his billionaire Republican rival, air millions of dollars of unanswered television ads that summer, only to emerge that fall, quite counterintuitively, as a fresh face for voters sick of the deluge.”

I wonder if Goldmacher happened to be in California in the fall of 2010. As of September 10, Meg Whitman was well on her way to becoming governor. (I was covering the medical marijuana movement. Whitman’s fellow Republican, Los Angeles District Attorney Steve Cooley was poised to become attorney general. She was strongly anti-union, he wanted to outlaw medical marijuana dispensaries. They were both ahead in the polls, Whitman very comfortably so.) Whitman was cruising along when Gloria Allred called a press conference to introduce Nicky Diaz Santillan, an undocumented immigrant who had been employed by the Whitmans as a housekeeper and nanny from 2000 through 2009. Meg Whitman had fired her at the outset of her campaign, telling Diaz, “You don’t know me and I don’t know you.” How cold can you get? Doesn’t the nanny raise the kids when mommy is busy running the company?

After the press conference, things got worse for Whitman. She claimed that she hadn’t known about Diaz’s immigration status. But Allred produced letters from the Social Security Administration notifying the Whitmans that Diaz’s supposed Social Security number belonged to someone else. Whitman next said the letters from the government had never been received. But Allred had a copy of one on which Whitman’s husband had written a comment. The well-publicized episode exposed not just Whitman’s personal disloyalty, miserliness, and cruelty, but her executive stupidity. When Meg Whitman decided to run for governor she could have hired a good immigration lawyer to straighten out Diaz’s status, and she could have provided ample severance pay to make ends meet until Diaz found another employer. Instead, she told her to get lost. “You don’t know me and I don’t know you.”

It was thanks to Niki Santillan-Diaz and Gloria Allred that Meg Whitman’s lead in the polls dissolved and California again wound up in 2010 with Jerry Brown —no friend of the working class, but not a Whitman-type ogre. And Brown is certainly not a moron. Whitman, after blowing $144 million of her own money on her run for governor, became the of CEO Hewlett-Packard and promptly made the news for spending $11 billion on a British software company that wasn’t worth 11 cents. Jerry Brown owed his margin of victory entirely to Nicky Diaz and her lawyer, Gloria Allred. Kamala Harris owed hers in part to the medical marijuana movement —especially California NORML for their online get-out-the-vote drive.