By Fred Gardner July 5, 2019 The International Cannabinoid Research Society (ICRS) held its 29th annual symposium this week in Bethesda, MD, home to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The society is made up mainly of scientists employed by universities and drug companies (increasingly, cannabis-oriented companies). NIDA has been its principal funder since the ICRS was launched in 1990. Government employees attending this year’s symposium got a discount rate for some reason.

The society is made up mainly of scientists employed by universities and drug companies (increasingly, cannabis-oriented companies). NIDA has been its principal funder since the ICRS was launched in 1990. Government employees attending this year’s symposium got a discount rate for some reason.

Cannabinoid research achieved a great leap forward in 1988 with the discovery of a receptor in the central nervous system that is activated by THC (partially). Investigators dubbed it the cannabinoid receptor (CB1), and assumed that the body produced an endogenous cannabinoid that activates it.

That compound was identified in 1992 as arachidonoylethganoalimine (AEA) and dubbed Anandamide (after the Sanskrit word for bliss).

In 1993 a second cannabinoid receptor (CB2) was found in the periphery. The endocannabinoid that activates it, 2-Archidonoylglycerol (2-AG), was identified in 1995.

The enzymes that synthesize and break down anandamide and 2-AG were also identified in these years.

Rosie and I first attended an ICRS meeting in 1998. It was there that Dr. Gabriel Nahas, the last die-hard denier of endocannabinoid signaling, rose from the audience to state his case. I was sitting next to Dr. John McPartland, who whispered, “Nancy Reagan’s favorite scientist.”

1998 was also the first ICRS meeting for Geoffrey Guy, MD, the founder of GW Pharmaceuticals. He had just gotten Home Office approval to develop a non-psychoactive cannabis-plant extract that would provide benefit to Multiple Sclerosis patients. The key to success, Guy explained in an interview, was using plants rich in cannabidiol (CBD), a chemical cousin of THC that negates its psychoactivity while providing anti-inflammatory and other helpful effects.

GW obtained CBD-rich plants by purchasing the genetic library of David Watson and Robert Clarke, US ex-pats who had traveled the globe in search of land-race cultivars and started a seed company in Amsterdam. Guy assumed that CBD had been bred out of the marijuana being grown for psychoactive effect in the US, but I told him with confidence that some would CBD-rich plants would be found when we got an analytic chemistry because the hills were full of growers who saved seeds from every unusual plant.

Back in CA I described the ICRS meeting in a leaflet that Dr. Tod Mikuriya photocopied and distributed to patients, and in Synapse, the UCSF newspaper. The first issue of O’Shaughnessy’s (Summer 2003), featured an ICRS update headlined “What Every Doctor Should Know About Cannabinoids.” Some 15,000 copies were distributed by clinicians and dispensaries.

O’Shaughnessy’s reports from past ICRS meetings are as relevant today as when first published, and reading them is worth three CME credits. (That’s a joke, but it’s figuratively true.) Recent cannabinoid research recapitulates and extends the findings reported at past conferences.

The great advances may be in the past, but this year’s ICRS meeting was the biggest ever. The abstract book lists 59 talks (12 minutes, plus three for questions) by scientists summarizing their recent findings, plus 184 posters. All the presentations have been peer-reviewed —an ICRS committee spends months reading abstracts and deciding whose studies are worth presenting and in what format. Giving a talk is considered more prestigious, but significant findings are often revealed at the poster sessions.

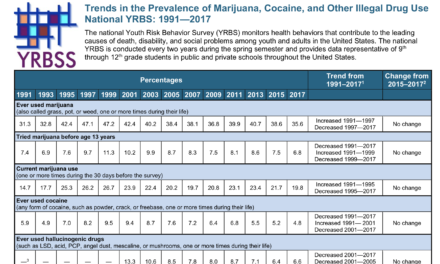

The Society of Cannabis Clinicians was represented at the meeting in Bethesda by Drs. Genester Wilson-King, Patricia Frye, Dustin Sulak, and Kevin Takakuwa, whose observations we hope to post (and now have). Takakuwa was lead author and Sulak a co-author on a poster, “The Education, Knowledge and Practice Characteristics of Cannabis Physicians: A Survey of the Society of Cannabis Clinicians.”

The poster shows that Family Practice, Emergency Medicine, and Pediatrics are the specialties from which most SCC members have been drawn. Hardly surprising, given the humane nature of Cannabis Medicine. —Fred Gardner