The Power of the Hed

Back in the day, newsroom wisdom had it that approximately 1/4 of readers would glance at the headline and not read the story, 1/4 would read only the lede (first graf), 1/4 would read to the bottom of the page, and 1/4 would jump to page whatever and read the whole piece. In this twittery age, the ratio of headline-only readers has greatly increased, for sure.

Writers usually suggest headlines, but editors usually write them —occasionally putting their own spin on the story at hand. In the print edition of the October 1 New York Times, for example, the two-deck hed over a front-page piece by Tim Arango and Shaila Dewan reads “Study’s Stark Finding: Over Half of Police Killings go Uncounted.” This is an accurate summary of the study, which was conducted by University of Washington researchers and published in The Lancet.

But the online editor chose to blunt the point by hedding it “More Than Half of Police Killings Are Mislabeled, New Study Says.”

Mislabeled in this context is an example of mislabeling. The undercount has been intentional and systematic, according to the story itself. With the complicity of medical examiners, “About 55 percent of fatal encounters with the police between 1980 and 2018 were listed as another cause of death.” Other excerpts follow:

“Researchers estimated that over the time period they studied, which roughly tracks the era of the war on drugs and the rise of mass incarceration, nearly 31,000 Americans were killed by the police, with more than 17,000 of them going unaccounted for in the official statistics. The study also documented a stark racial gap: Black Americans were 3.5 times as likely to be killed by the police as white Americans were. Data on Asian Americans was not included in the study, but Latinos and Native Americans also suffered higher rates of fatal police violence than white people.

“The annual number of deaths in police custody has generally gone upward since 1980, even as crime — notwithstanding a rise in homicides last year amid the dislocations of the coronavirus pandemic — has declined from its peak in the early 1990s.

“The system has long been criticized for fostering a cozy relationship with law enforcement — forensic pathologists regularly consult with detectives and prosecutors and in some jurisdictions they are directly employed by police agencies… The researchers found that some of the misclassified deaths occurred because medical examiners failed to mention law enforcement’s involvement on the death certificate, while others were improperly coded in the national database.

“Dr. Murray of the University of Washington said that one of the starkest findings was that racial disparities in police shootings have widened since 2000.

“The study, he and other researchers said, points to the need for a centralized clearinghouse for data on police violence, as well as more scrutiny of coroners and medical examiners.”

Another Example

Laid out just below the Uncounted Police Killings story was one about the refusal of workers at Dollar Tree stores to tolerate intolerable working conditions and inadequate pay. The accurate hed in the print edition read, “Low Pay and Worker Burnout Add to Dollar Stores’ Troubles.”

The online editor had it as “‘Everything Going the Wrong Way’: Dollar Stores Hit a Pandemic Downturn.” Which sounds like the CEO’s lament.

The Giants Stole the Pennant! The Giants Stole the Pennant!

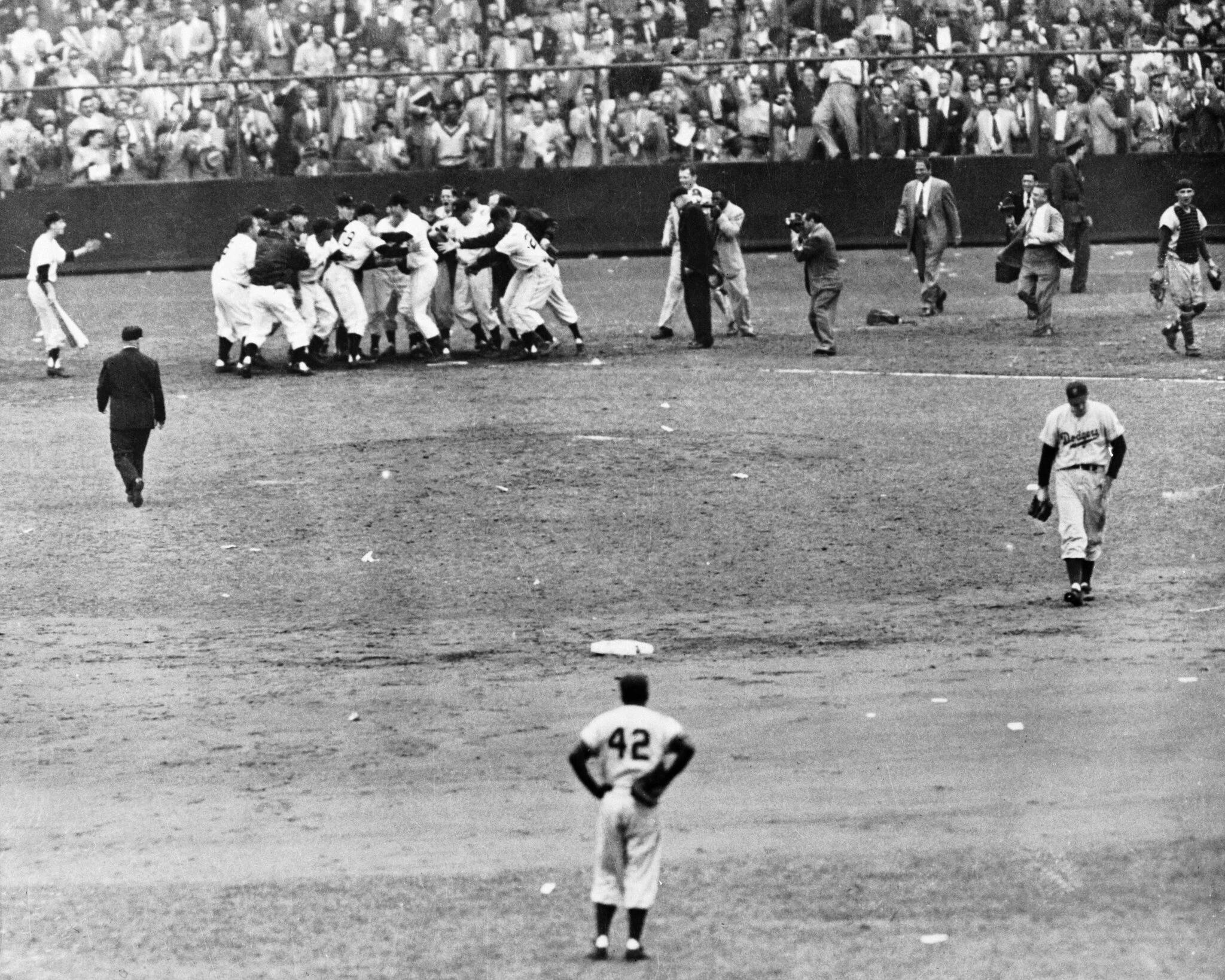

On October 3, 1951, Bobby Thomson hit a home run off Ralph Branca in the ninth inning of the third and deciding game of the playoffs. Thus ended a pennant race the Dodgers had once led by 13 games. This was a very sad day for the people of Brooklyn Before Gentrification. Collective grief swept over the borough and into the hearts of Dodger fans everywhere. We had a famous saying, “Wait till next year,” but on that night it rang hollow. In 1955 next year finally came, but then Walter O’Malley moved the team to Los Angeles. Horace Stoneham, in on the deal, brought the Giants to San Francisco. And that was the dawning of the Age of Air Travel.

On October 3, 2021, the Times ran a piece by George Hirsch recalling the day Bobby Thomson hit “the shot heard round the world.” Hirsch, now the publisher of New York Magazine, was then a high school student in New Rochelle, an affluent suburb. He and some friends played hooky and drove in to the game. (Hirsch owned a car.) Tickets were available at the Polo Grounds because there’d been no advance sales, people assumed it would be a sell-out, and there was no internet to report otherwise.

Describing the tragic last pitch, Hirsch defers to Don DeLillo, whose novel Underworld hinged on it: “Not a good pitch to hit, up and in, but Thomson swings and tomahawks the ball and everybody, everybody watches.”

Back in New Rochelle that night, a supportive father told Hirsch that someday he would get over it. “Someday, I hope I will” is his maudlin punchline in the Times.

But Mr. Hirsch has gotten over it. He’s just a rich kid from New Rochelle expressing his mild self-pity after all these years. A true-blue Brooklyn Dodger fan would have used the opportunity to remind the world that the Giants won that game —and the 1951 pennant— by cheating.

The Giants’ tainted triumph was commanded by their manager, Leo Durocher (famous for the phrase, “Nice guys finish last”) and exposed by Joshua Harris Prager in the Wall St. Journal 50 years after it was perpetrated. This being the United States of Amnesia, truths can be revealed and then forgotten without making more than a slight dent in the public memory. Prager wrote, “The Giants were stealing the Dodgers’ signs, the finger signals transmitted from catcher to pitcher that determine the pitch to be thrown… ‘Every hitter knew what was coming,’ says 83-year-old Al Gettel, a pitcher on the 1951 Giants roster into August. ‘Made a big difference.'”

An investigator on a mission, Prager interviewed all 21 surviving players and the one living coach. “Many are at last willing to confirm that they executed an elaborate scheme relying on an electrician and a spyglass,” he wrote. “And, they say, they stole signs not only during their encounter with the Dodgers, but during home games all through the last 10 weeks of the 1951 season, a period when the Giants appeared to summon mysterious resources of will and talent…

“The Giants’ clubhouse looked out on the diamond from high above the center-field wall —483 feet away from home plate in 1951, an absurdly long distance by Major League standards. Mr. Durocher, who died in 1991, told his players that their clubhouse, directly aligned with home plate, was the perfect crow’s nest for stealing signs.

“The matter remained of somehow relaying the signs to the batter from behind a wire-mesh screen in the clubhouse. There were no lights in the scoreboard, so flashing a bulb was out of the question. However, the bullpens, where pitchers warmed up, were in fair territory along the outfield walls. When a batter stepped to the plate, he could look just to the right of the pitcher and see his teammates much farther beyond, on a bench in right-center field. Though they sat between 440 and 449 feet away, they could motion their signals unimpeded.

A man named Abe Chadwick relayed the signals from the clubhouse to the bullpen by means of a buzzer. (Abe Chadwick’s brother, an official at Local 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, had gotten him a kind of sinecure at the Polo Grounds. His whole job had consisted of turning the lights on before games and off afterward.) Discerning the signs for Chadwick by means of a high-powered telescope was a failed infielder named Henry Schenz. According to the WSJ, “Focused on an object 500 feet away, a 35-millimeter lens like the one in Mr. Schenz’s telescope provides a resolution of about 0.2 inch. And so, peering through the spyglass from a perch in Mr. Durocher’s locked office in the clubhouse, Mr. Schenz could have distinguished the tips of catchers’ fingers spread at least 0.2 inch apart.”

Giants’ hitting mysteriously improved starting in late July. In August they won 16 games in a row.

Only about half the players wanted the secret advantage, according to a relief pitcher named Corwin. Dignified Monte Irvin, a great Negro Leagues star who had come to the Giants past the age of 30, told the WSJ that Durocher “asked each person if he wanted the sign. I told him no. He said, ‘You mean to tell me, if a fat fastball is coming, you don’t want to know?’ ”

By September, Jacobus wrote, “relaying signs from the dugout, where chosen players could shout code words to batters, was deemed too conspicuous. The Giants were mainly relaying signals from the bullpen. The player relaying would sit closest to center field. After hearing the buzzer buzz, he might cross his legs to denote a fastball. He might toss a ball in the air. He might sit still…

“Another change: Mr. Schenz was no longer the spy in the clubhouse. He had struggled to decode the opposing catcher’s signs. Herman Louis Franks, the Giants third-base coach in 1951, had been a catcher. Like all catchers, he knew signs and how to mask them when runners led off second base.”

(Franks would become the San Francisco Giants manager for four seasons, 1965-68. His teams, despite having Mays, Marichal, and McCovey, finished second every year.)

The shot heard round our apartment

Your correspondent was about to turn 10 when Bobby Thomson hit “the shot heard round the world.” My father had given me a small job —not much harder than Abe Chadwick’s— for which I received $5/week. Every evening I listened to a radio show on WNEW called the “Sports Show Kase,” on which a Journal-American sportswriter named Max Kase would report the day’s news and narrate some stories. Some of those stories had been written by my dad, who was then free-lancing and hustling full-tilt. Kase paid only for the material used on air, and my dad was guarding against a rip-off by keeping track of each program. (My dad had worked for the Journal before World War 2. The newspaper industry was shrinking fast.)

On the evening of October 3, 1951, I announced that I could not bear to hear Max Kase retelling the tragic day’s events. My dad said I had to, it was my job. I protested vehemently. I think it was the only time I ever yelled at him. My mother tried to intercede on my behalf, and though she usually ran the show, my mild-mannered old man thought there was an important principle to be instilled. I slammed out of the house with the intention of running away forever. After a few hours roaming Broadway, I got hungry and wound up at my aunt’s house, where I got sympathy and leftover meat loaf. It’s very important to have aunts and uncles nearby. Here’s to the extended family that lives close to one another!