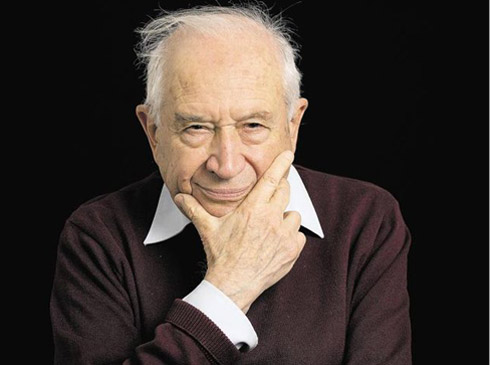

By Fred Gardner Many of us who get interested in cannabis as medicine get very interested and want to learn more about how it works. One of the first facts you pick up is that the chemical structure of THC was worked out and published in 1964 by Israeli pharmacologists Raphael Mechoulam and Yechiel Gaoni.

It’s not so well known that Mechoulam has been conducting and guiding cutting-edge cannabinoid research all these years. Zach Klein’s beautifully filmed documentary, The Scientist, recounts Mechoulam’s role in discovering and elucidating the endocannabinoid system and proposing clinical applications for cannabis-based medicines. Read O’Shaughnessy’s detailed review here.

Klein is one of those people who got very interested in cannabis. His 2011 documentary Prescribed Grass told the story of Tikun Olam, Israel’s pioneering medical cannabis collective (a group Klein helped organize).

In The Scientist, Klein plays the curious Everyman who questions Mechoulam about cannabis and how it works in the body. (Klein’s face is handsomer and more expressive than Everyman’s.) The interviews are conducted in the pleasant Jerusalem apartment where Raphe and Dahlia Mechoulam have lived since 1966, and in Mechoulam’s lab at Hebrew University, and in his car as the scientist drives to and from work, and at a meeting of the International Canabinoid Research Society (a group Mechoulam helped organize).

Klein occasionally carries a potted cannabis plant —a signature prop, like Charlie Chaplin’s cane.

Although Mechoulam’s manner is gentle and undemanding, he is making a strong plea in The Scientist: cannabis-based medicines should be made available to patients. He does not point an angry finger at any government or agency that has impeded progress —he shrugs in disappointment.

In response to Klein’s first question, Mechoulam observes (in the mildest, sweetest tone of voice) that cannabinoid medicine “is not being used as much as it should be in the clinic. It is of great promise in the clinic [meaning ‘in the treatment of patients’]. Maybe this film can push it forward a bit.”

Klein asks why, at the start of his career, Mechoulam chose to study the active compound(s) in cannabis.

Mechoulam replies, “Well, a scientist should try to find topics of importance…

“Doing research in a small country with a very limited budget, my philosophy was that one should try to find out topics that are not being pursued by the major groups throughout the world. We cannot compete with them… We should try to find —by studying the literature, by thinking about important projects— we should follow research pathways that were not being followed by major groups. Nobody was working on cannabinoid chemistry. So we thought at that time that this was a project worth following.”

In 1962 Mechoulam applied for a grant from the US National Institutes of Health. “But NIH wrote me back,” he tells Klein, paraphrasing: “The topic you’re interested in, namely the constituents of Cannabis sativa, is not a relevant topic for the U.S. It’s not used int the U.S. When you have something more relevant, ask us for a grant.”

About a year later, Mechoulam got a phone call from a high-ranking NIH pharmacolgist who was interested in cannabis.

AXELROD? WHO CALLED? “All of a sudden they had a change of mind. So I asked them what happened. Well, apparently someone high up —an important person, maybe a senator— had called NIH and asked, ‘What does Cannabis do?’

“It seems that his son had been caught smoking pot. He wanted to know if marijuana destroyed his mind. They didn’t know anything about marijuana…

“So the pharmacologist came over and asked if I was still working on it and I said yes, we had just discovered the active compound and we had a large amount —about 10 grams of THC.

“So he said, ‘Please give us the 10 grams and we’ll do a lot of pharmacology in the U.S.’” Mechoulam complied. “So he got the world’s supply of THC, took it to the US —actually, he probably smuggled it because I don’t think he had a license to take it to the U.S. But then of course nobody was looking for THC, it was not a known compound. So he took it to NIH and for the next couple of years most of the research on THC in the U.S. was done with materials supplied by us —those grams that they took.

“And for many years —nearly 45 years— I was supported financially by the National Institutes of Health. And they never, never interfered with my research.”

The hashish from which Mechoulam isolated THC and CBD in the early ‘60s had been obtained from the police in Jerusalem. Bringing it back to his lab on a bus, Mechoulam drew inquisitive looks and remarks from fellow passengers puzzled by “this very unusual smell.” His reminiscence is brought to life in The Scientist by the formidable Swiss-based cartoonist Ivan Art.

Mechoulam shows Klein (and us) a glass column like the one he and Gaoni used all those years ago to separate out “10 or 12 compounds” from their hashish. Of those compounds, only one was found to be active. (Activity was defined as having a sedating effect on monkeys).

That one active compound, Mechoulam explains, “now named delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol —THC— causes, essentially, all the hashish type cannabis type effects.”

With basic safety having been established in the medical literature going back centuries and confirmed at the monkey colony, the logical next step was an experiment with humans.

“We had a few of our friends take 10 milligrams of pure THC on a piece of cake my wife prepared,” Mechoulam recalls. “And five took only the cake without the THC, and we compared the effects.

“None of us had ever used cannabis before. As a matter of fact very few people had used cannabis at that time in Israel.”

“All those that took the THC were affected,” Mechoulam tells Klein. “But surprisingly, they were affected differently. Some said, ‘Well, we just feel kind of strange, in a different world. We want to sit back and enjoy.’

“Another one said ‘Nothing happens’ —but he didn’t stop talking all the time. A third one said, “Well, nothing’s happened. But every 15, 20 seconds he would burst out laughing.

One of the participants experienced anxiety. Mechoulam says. “She felt, I believe, that her psychological guards… are breaking down and all of a sudden she was open to everybody. So she really got into an anxiety state.

Mechoulam observes, “These effects are well-known today. People are differently affected. In some cases we definitely see anxiety attacks. Most do not [experience anxiety]. Most just feel kind of a little bit disoriented. Just maybe a little bit sedated. Maybe a little bit open to discussion and socially open to whatever is being discussed.”

Note Mechoulam’s use of “maybe” and “I believe.” He abjures strong assertions and tends towards understatement, as if his knowledge is provisional.

“It’s not just he discovered THC… but he continued to have such a vision for the next step and the next step and the next step.”

—Mahmoud ElSohly

Promoting research

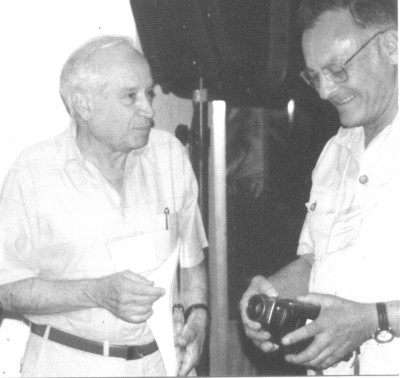

Among Mechoulam’s colleagues interviwed in The Scientist is Mahmoud ElSohly, famous for growing the marijuana that the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) provides to researchers. ElSohly tells Klein (and us) that Mechoulam has never rested on his accomplishments, is always seeking to advance research. “It’s not just he discovered THC… but he continued to have such a vision for the next step and the next step and the next step.”

Klein filmed Mechoulam attending a meeting of the International Cannabinoid Research Society in Freiburg, Germany, in the summer of 2012. “I feel that Dahlia has to be next to me if I want to survive on a trip,” he comments. “Meetings are useful in many ways. People learn what other people are doing and going to do…People from different aspects of a topic talk to each other and maybe something new comes out.”

Ideas also come from a respectful reading of centuries-old texts.

“So the field kind of told us: ‘Try it on epilepsy.’”

Mechoulam recalls his role in advancing a Brazilian study of CBD as a treatment for epilepsy, telling Klein (and us) of “an Arab story from the 15th century and it says that one of the Arab leaders had epilepsy. A physician came over and gave him cannabis and it cured him. But he had to take it for his entire life.

“So the field kind of told us: ‘Try it on epilepsy.’

In other words, from Mechoulam’s POV, it was not his original insight that cannabinoids would have anti-seizure effects, it was a logical conclusion from reading one’s scientific ancestors. What a modest way to describe his role! And how revealing about insight itself!

The Brazilian study, Mechoulam goes on, was conducted after “we first tried it on animals and it worked. Trials took place in Sao Paolo. They had about 10 people who had epilepsy that could not be affected by the known drugs. We started giving them high doses of cannabidiol —200 mg per day…

“And it was published. And nothing happened afterwards.”

“We were happy to note that indeed they had no seizures while they were taking cannabidiol. And it was published. And nothing happened afterwards. So far, 34 years later, this is the only publication of cannabidiol in humans against epilepsy.”

“I was very well aware…”

Raphael Mechoulam was born in 1930 in Sofia, Bulgaria, where his father was a physician in private practice and also head of the Jewish Hospital. “I was a child during the war,” Mechoulam tells Klein. “So I was very well aware of what was going on.”

When anti-Jewish laws were enacted, Mechoulam says, the family moved to a series of small villages where a doctor was needed and respected. “But at some point somebody decided that my father should be taken to a concentration camp,” Mechoulam says. Dr. Mechoulam was released, apparently in appreciation for his heroic usefulness after a fire destroyed the camp.

“Luckily,” Mechoulam goes on, “the Bulgarian Jews were not killed. The conditions were bad enough, but Bulgarian Jews were not killed. My uncle saved them…”

With a twinkling eye, Raphael Mechoulam tells Klein how his uncle saved the Jews of Bulgaria from the Nazis’ extermination camps. We won’t spoil it. You’ve got to watch this movie for yourself.

Like most Bulgarian Jews, the Mechoulams emigrated to Israel after World War Two. After a stint as a land surveyer, Mechoulam spent three years in the army, which had him doing research on insecticides. He got his PhD degree from Hebrew University “on the topic of natural products related to biological problems.”

After doing post-doctoral research at the Rockefeller Institute in Manhattan, Mechoulam took a position at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, which is where he and Gaoni isolated the compounds in hashish. Mechoulam joined the Hebrew University faculty in 1966.

Receptor and agonist

“Plant cannabinoids,” Mechoulam tells Klein “had been evaluated in the test tube, they had been evaluated in animals and to a certain extent in human patients. But nothing was known at that time about the mechanism.”

“Receptors are made for compounds that we produce, not because there is a plant out there.”

In 1988 the finding of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain by Allyn Howlett and colleagues at the St. Louis University School of Medicine was characterized by Mechoulam as “a major, major discovery —the first indication that THC acts on on a receptor.”

Undoubtedly, Mechoulam points out, “Receptors are made for compounds that we produce, not because there is a plant out there.”

The next challenge for scientists was to find the body’s own endogenous cannabinoids, “In my lab there were three collaborators who contributed a lot in this research,” Mechoulam tells Klein, as he enters a room where two of those collaborators —Lumír Hanuš and Aviva Breuer— are still at the bench.

Hanuš explains that he came from Czechoslavakia 23 years ago “just for one year, and got a little bit overextended.” Already working with Mechoulam as of 1991 was Bill Devane, who played a key role in Allyn Howlett’s lab when the receptor was identified.

“We initially worked on brains of pigs,” Mechoulam says of the search for the endogenous cannabinoid. “It is generally accepted that the organs of pigs and the organs of humans are somewhat closely related. And probably pigs and humans are also somehow closely related. Well, I’m not sure that the pigs will be very happy to be related to humans, but that’s something else.

“So we wanted to work on pig brains and pig brains are not so easy to get in Jerusalem.” A butcher was found in Tel Aviv who supplied the brains readily at first, but began charging as he realized that his new customers had an ongoing need for the material.

“Each time when we came to buy it again, the price was higher,” Hanuš recalls. “At the end it was very expensive.”

Devane explains how he would take a thin slice of the brain material “and put it over a silica sand column and separate a few fractions and test them [radioactively tagged] for how they bound to the receptor. And I thought, ‘Oh, it won’t take long.’”

But when Hanuš’s year came to an end, the endogenous cannabinoid had still not been isolated. “So we asked Professor Mechoulam to extend,” Hanuš tells Klein.

Other scientists were seeking to identify the endogenous cannabinoid, and Devane says that Mechoulam “thought we might be scooped by some other lab.” But he kept Devane and Hanuš on the project and in 1992 they isolated a small amount of compound they identified arachidonoyl ethanolamide.

“It was only like a few droplets in the end of a little test tube,” Devane remembers.

The task of confirming that the newly discovered compound had the properties that define a cannabinoid was carried out by University of Aberdeen pharmacologist Roger Pertwee.

Devane, who had studied Eastern philosophy, proposed that the newly identified cannabinoid should be named for the Sanskrit word for bliss, ananda. “Although some people do not agree with me,” Mechoulam tells Klein, “in Hebrew there are not too many names for happiness. For sorrow you can find a lot of names, but… not for extreme happiness.”

Because the compound was an ethanol amide, and amide fit nicely behind the Sanskrit root, the endogenous cannabinoid was dubbed “anandamide” —a name that says something about its effect and its chemical structure.

The 1992 paper by Devane et al announcing the “Isolation and Structure of a Brain Contituent that Binds to the Cannabinoid Receptor” had been cited 4,342 times as of 2014. “They don’t cite it any more,” Mechoulam tells Klein, uncomplainingly, “because it’s considered such a well-known thing, an obvious thing…. They mention that anandamide does A and B and C.”

The endocannabinoid system

In addition to directing research in his own lab, Mechoulam has been at the center of a vibrant entourage, disseminating ideas and encouragement worldwide. The Scientist includes a montage of ICRS investigators acknowledging Mechoulam’s guidance: Andreas Zimmer, Heather Bradshaw, Rafael Maldonado, Mauro Maccarone…

It was Mechoulam who inspired Ethan Russo and Vincenzo DiMarzo to think in terms of entourage effects —compounds acting in concert— instead of single molecules. It was Mechoulam who urged Itai Bab to explore the role of endogenous cannabinoids in bone, and Ester Fride to study their role in the birthing process and breastfeeding.

Mechoulam notes matter of factly that nowadays “a huge number of researchers are involved in investigating this system from many aspects… A very serious group of researchers has recently published a paper saying that the endocannabinoid system is involved in essentially all human diseases.”

Hashish for Children

Klein reminds Mechoulam, “In 1995 you had an idea of testing THC on children.”

It had long been known, Mechoulam says, that cannabis reduces the nausea brought on by anti-cancer drugs. Children given these drugs “vomit and want to vomit —nausea— they’re really in a bad shape. And they cry all the time and their parents are in a bad shape. Luckily, most little children can be cured of the cancer. But the treatment is absolutely difficult.”

Mechoulam arranged for a clinical trial led by pediatric oncologist Ava Abramov. “Obviously children cannot smoke. We had children that were not even one year old. She dropped THC in olive oil under the tongue two or three times a day, small doses, during the anti-cancer treatment.

“In the begining we wanted to do a double-blind study. Some of the children got the THC, some other children got only the olive oil. After a week she told me ‘I’ m not going ahead with that. I know exactly who is getting the THC. I know exactly who is not getting it.’

“There was a complete separation. Those that didn’t get it continued to vomit. So she went ahead doing an open study. She gave THC —pure THC— under the tongue about 400 times [during the course of a child’s treatment]. And at the end we had complete —complete— block of vomiting, a complete block of nausea by a small amount of THC. We did not cause any psychoactivity, nothing.

So here we had a complete therapeutic effect and we published that, and again, essentially nothing happened. Finito, that was it. It’s still not being used in children.”

Klein repeats the conventional challenge: “And you think it’s a good idea to use it for children?”

Mechoulam has no misgivings. “Well I believe it’s an excllent idea because we help those children that suffer. But I have no influence on oncologists.” He shrugs and smiles ruefully.

Cut to Allyn Howlett re-enforcing the point, ardent: “If there is a cancer patient who’s got pain and that pain is not being controlled well by other tytpes of drugs, they’re on cancer chemotherapy, they’re vomiting I think it’s unethical to withhold a drug from them that can be very useful to help them in their pain management and in their ability to cope with their disease.”

Can cannabis cure cancer?

Klein asks, “Can cannabis cure cancer?” Mechoulam answers: “We know that THC lowers the [nausea] effects of cancer treatment. But what you’re asking is ‘is it an anti-cancer drug?’ And the answer is, ‘I don’t know.’ And the reason for that is silly.

“It has been tested in the test tube. THC has been tested, cannabidiol, crude cannabis and yes, in many cases it blocks the development of cancer cells. Yes.

Mechoulam notes the findings of Manuel Guzman, then restates his main theme: “Though we have done quite a lot in the field of cannabinoids and endocannabinoids, we have not done enough in clinical trials. This is something that has to be done. If this is not done we will certainly miss a lot and we will not be helping human patients. It should be done.”

A recurring dream

Klein asked Mechoulam, “Do you have a dream?” The answer was earthbound and poignant: “I have one dream that comes on and off in very different ways. I’m in a city that I don’t know. and I don’t know how to go back to the hotel I’m staying and I don’t remember the name of the hotel and I get into an anxiety and I wake up. And this has happened many times. I think it has to do with whatever happened in the Second World War when my parents told me ‘Remember these names and these addresses.’ Because if we disappear, you should go there. Which is, well, not very pleasant, which is quite a shock, probably, to a child. And of course we were very afraid that we’ll be separated, my parents and I. I was afraid.

I now remember more than I did over the many, many years that have passed since then. Older people, they start remembering things that happened in their childhood.”

Mechoulam describes a study in which cannabis “seems to be helping the symptoms of Alzheimer… Alzheimer at the moment is a huge, huge problem and there is very little that can be done for Alzheimer’s patients. So maybe if it is well researched in the future, we should know how to help these patients… We are lucky that cannabis is not toxic.

The Scientist ends with a clip from Mechoulam’s 2012 talk to the International Cannabinoid Research Society.

“And now I’d like to end with something that is really crazy speculation,” he says. “Each one of us has a different personality and we have no idea why. Why do we have different personalities? Part of it is the effect of the environment, okay. But part of it is genetic. And we don’t know why we have different personalities.”

Mechoulam elaborates to Klein: “One way of explaining it is there are several hundred endocannabinoid-like compounds —they are like anandamide in their chemical structure— present in the brain.

“And it’s quite possible that each one of us has a slightly different level of these compounds. This is genetic. This is based on the different DNA of everybody. But DNA doesn’t affect the personality —It is the compounds that are formed from DNA through RNA to proteins and peptides and secondary compounds. So it is quite possible that differences in the endocannabinoid system—the endocannabinoid-like system—can have something to do with the different personalities. Well, that’s a very complicated story, but it may work.”

Mechoulam tells his colleagues in Freiburg that a mathematician confirmed that different combinations and permutations of 200 fatty acids could account for 8 billion distinct personalities. “This is crazy speculation,” he repeats, “but at some point we’ll have to find the biochemical basis of why we are different.”