Being the son of a great man isn’t easy

As a reporter I had seen Terence Hallinan in some very dramatic situations over the years. In an Army courtroom defending 14 Presidio stockade prisoners charged with mutiny. At City Hall in San Francisco, imploring his fellow supervisors to pass a resolution enabling Dennis Peron to distribute marijuana to AIDS patients. In a Sacramento hotel ballroom advising California law enforcement officials —some 350 district attorneys, police chiefs and sheriffs, all of whom had opposed Proposition 215— to leave its implementation up to their public health departments… But it was a mundane image from 2002 that the slide projector in my mind chose to display when I heard that Terence had died.

Terence, then 65 and the district attorney of San Francisco, was in the driver’s seat. The lone passenger was me, his press secretary. He had pulled over and parked on 10th Street between Market and Mission to point out a huge chasm on which a new office building would soon be erected. “That could be the new Hall of Justice,” he said in an unusually wistful tone. “I want it to be called ‘the Vincent Hallinan Hall of Justice.'” Terence gazed at the hole in the ground for a while before adding, “The mayor knows how much it means to me.” Then he pulled out and drove back to 850 Bryant Street (where the Hall remains to this day).

Vincent Hallinan was an impossible act to follow. Terence, the second-oldest of his six sons, was the only one who spent a lifetime trying (though they all admired and were devoted to him). Terence once gave me a biography of his father, “San Francisco’s Hallinan: the Toughest Lawyer in Town,” by Joseph P. Walsh. I skimmed it back then and read it just now.

Vincent was born in San Francisco in 1896. His father, Patrick, had emigrated from County Limerick and worked on the cable cars. He met and married Elizabeth Sheehan, a pretty maid (servant in a wealthy household). When the Carmen’s Union struck for an 8-hour day, United Railroad brought in scabs and armed strikebreakers and turned their car barn into an armory. In the battles that ensued, 239 men were wounded and three union men killed. Patrick Hallinan was clubbed, leaving him with a misshapen right hand and a long scar from above his left eye to his hairline.He gave up on militance, found odd jobs, drank heavily, and the family kept moving into ever cheaper rentals as babies kept arriving. There would be six girls and two boys sleeping four to a bed.

During the 1906 earthquake the lodging house they were living in fell off its foundation. Terence’s brother Conn “Ringo” Hallinan says that according to family lore, 10-year-old Vince ran to his parents and asked, “Dad, did you do that?” (“Which says something about the Irish and patriarchy,” Ringo adds.) The family camped out in Golden Gate Park for a few months, then Elizabeth moved with the kids to a cottage in Petaluma that had no gas or electricity, while Pat stayed in the city to work.

At age 12 Vincent got a job delivering groceries for $1.50/week plus surplus produce. When he was 16 Elizabeth moved back to San Francisco and her husband (who had found work driving a horse and wagon for the city) so that Vincent could be educated by the Jesuits at St. Ignatius. He excelled during three years of high school and earned a BA from the college (now USF). During his junior year he enrolled in night law classes and found his calling. He apprenticed to an experienced lawyer named Ryan and at age 24 —before he had his law degree— passed the first-ever written exam administered by the state bar association.

He worked 72 hours a week, did thorough research for every case, argued cogently and forcefully, and won most of the personal injury suits and civil-court actions he brought. He only charged clients if he won and his usual fee was 33% of the award. “Earning money never constituted a problem for Hallinan, even at the start of his legal career,” according to Walsh, his biographer. He often didn’t charge Irish laborers who were supporting large families. His first major purchase was a house in the Haight-Ashbury for his own.

Vincent Hallinan didn’t attend mass but he helped build a social club for St. Agnes parish, which became extremely popular with young unmarried Catholics throughout the city, staging musicals and monthly dances. He also led the Agnetian Club football team from a no-win season in 1921 to the Pacific Coast Club championship in ’24.

“Hallinan invented a new defensive tactic, the ‘roving center,'” Walsh writes in his bio. “On each of the opponent’s plays Hallinan would stay at center only if the ballcarrier was coming at him, otherwise he would pull out of the line and follow the play, thus adding his strength to the threatened position.”

Pro football soon reached San Francisco, the top players were lured away from the clubs and the Agnetians disbanded. Walsh recounts: “Hallinan had captained the team during its entire history and played every minute of each of its 28 games. Ripley’s ‘Believe it or Not’ commemorated his endurance record and designated him ‘The Iron Man of Football.’ His enduring contribution to modern football evolved from his ‘roving center’ device. Coach ‘Pop’ Warner introduced it at Stanford with All-American results. Thereafter, the innovation became nationwide and developed into the position of linebacker.”

In 1925, Vincent took his first criminal defense case at the request of the Hallinans’ milkman. His client was an elderly ranch mechanic named Johnny Tipton, who was facing a murder charge in Hanford, a town in the Central Valley. The dead man, whose life had been very heavily insured, was the foster son of Tipton’s niece; his will made her the main beneficiary. Hallinan ascertained that the grand jury had been led on a tour of the death scene not by the district attorney but —illegally— by a detective working for the insurance companies seeking to escape liability by pinning the rap on Tipton. Hallinan’s motion to get the case dismissed was denied and he spent three months in Hanford arguing in vain in a sweltering courthouse packed with hostile spectators. He was twice cited for contempt and paid $500 in fines, but he was confident that Tipton’s conviction would be overturned and in due course it was.

Back in San Francisco Hallinan resumed winning civil suits and building his practice. His football days were done but he took up swimming, rugby, and boxing. He joined the prestigious Olympic Club and sparred regularly with his close friend from St. Ignatius, John Willams (6′ 4″, 280 lbs.), who had won the national amateur heavyweight boxing championship. Willams convinced him to make some small stock purchases. Hallinan then made a study of economics, decided that the market was “a racket,” and sold off his holdings, netting $109,000 a few months before the market crashed. He leased a suite of offices in the newly constructed Russ building and bought a large redwood cabin near the newly constructed Hetch-Hetchy Dam. He had a boxing ring installed there and worked out often with Willams.

“Fighting was as natural to Hallinan when he was angry as laughing when he was amused,” his admiring biographer explains. Hallinan told Walsh that he had punched out 26 lawyers whose behavior in court angered him. The 27th was a younger, bigger lawyer who had boxed professionally and got the better of him. “The aura of physical primitivism never embarrassed Hallinan; he cultivated it,” writes Walsh. “This was particularly true after rugby and football injuries disfigured the left side of his face and his left hand. By the 1930s corridor beatings had become unfashionable… As late as the 1970s Hallinan hit young attorneys who had lost their composure and called him vulgar names.”

Hallinan fought judges, too —not with his fists but by pressing for reform of the civil court system. Judges and jurors were assigned to cases by a commissioner in thrall to the transportation and insurance companies. (The most frequent defendant was the Market Street Railway.) In six consecutive cases that Hallinan won in the 1930s, judges found insufficient evidence for the award to his client and ordered retrials. Hallinan determined that in 61 cases tried by the two most biased judges, only five verdicts against the Market Street Railway had been allowed to stand, and the awards were trivial. He began filing affidavits claiming partiality and demanding a hearing whenever he had a case assigned to a judge he knew to be biased. The newspapers covered his campaign, his cases began getting reassigned, and his reputation soared along with his won-loss record. Following a review of the system by outside judges in 1937, reforms were instituted. These included selection of jurors from the voter rolls and assignment of cases by a rotating presiding judge.

In 1932 Hallinan’s client Frank Egan, the San Francisco public defender, was found guilty of killing his wife but spared the death penalty. Hallinan did a day in jail for contempt; Egan would do 25 years. Also in 1932 Franklin Roosevelt was elected President and Vincent Hallinan, 35, married Vivian Moore, 21, who was majoring in history at UC Berkeley. It was a perfect match intellectually. Plus: she was a self-confident knockout and he was a big, handsome man with a few battle scars. He had money and they both had class. He’d been a ladies man and intended to remain a bachelor. She dreamed of having six sons and a stable home. (Her Irish father and Northern Italian mother divorced when Vivian was very young and she was raised by various relatives.) Hallinan was an outspoken atheist and she was a free thinker, but they were married by a priest in Reno, hoping to please his parents.

Vivian immediately got into real estate and soon, although the depression was deepening, started making money. She renovated, rented out, and then sold two extremely rundown apartment buildings near San Francisco’s business district that had fallen to Vince in lieu of payment. She would reflect: “I wanted to do something myself and I did not want him to dominate me or run my life. My subordination and dependence were undesirable for both of us.”

2. Conversation With Ringo

Conn “Ringo” Hallinan (who is six years younger than Terence) says of his mother: “When the depression hit she had cash, which was rare, so she got great deals. Also, she was the first landlord in San Francisco to provide furnished apartments. She would go into the big furniture stores and say, ‘I need this, I need this… and I want 50 percent off.’ They’d say ‘You’re out of your mind.’ And she’d say, ‘Well, I need a hundred of them.’ And they’d say ‘Oh. We do 50 percent off.’ She had savvy. She had a philosophy of charging renters below market rate. That resulted in two things: you never had vacancies and you never got sued. And it made her feel better about what she was doing.

Ringo once told me that their father made the Hallinan boys swim around the lake down the road from their cabin every morning before breakfast. (I call him “Ringo” because that’s what Terence called him. I used to call Terence “Kayo” before I went to work for him.) The other day I phoned Ringo to ask, “And what if you weren’t up to swimming around the lake?” He said, “You don’t talk back to the burning bush.” One time his father wouldn’t let him get off the diving board, he said, until he executed a dive he was too afraid to attempt. “He kept me up there for an hour and a half because I was scared to do a one-and-a-half.”

Not easy being the son of a great man. “Not at all,” Ringo confirmed. “I remember when he had us us go into the Merced River at the end of April —and it was good for us. The Merced River is too cold to swim in at the end of August. In April?”

“Why was it good for you?” I asked.

“Because it showed you were tough.”

At a reunion of the Presidio “mutineers,” Randy Rowland said that Terence Hallinan had told him frankly at their first meeting in the summer of 1968, “I’m a Communist.” Rowland was then an Army medic on orders for Vietnam who had been turned against the war by wounded soldiers he had been caring for at Fort Lewis, Washington. He was AWOL and drafting an application for conscientious-objector status when he sought Terence’s advice on how to turn himself in in a way that would advance the anti-war movement. I had to overcome a taboo to ask Ringo Hallinan if Terence had been speaking literally or figuratively when he described himself as a Communist. Growing up in Brooklyn during the post-World War II Red Scare you learned not to make such direct inquiries. But on the West Coast the left had not been pervaded by fearfulness and Ringo responded readily: “Terence was kind of in the party. I was in the party so I can tell you that he wasn’t a member in the real sense of the word.

“My parents were never members of the Communist Party,” Ringo added. “They never said anything bad about the party, although they had good reason to, because they saw the role that anti-communism was playing. They didn’t want to give it any credence. In 1952 my father ran for president on the Progressive Parthy ticket. The Communist Party was the heart of the Progressive Party, the people who did all the work. But right before the election the Party decided that fascism was coming and they had to support Stevenson to stop fascism —another one of their completely bonkers decisions.” (Adlai Stevenson had been the Democratic Party candidate in ’52; Dwight Eisenhower won in a landslide.) The CP honchos didn’t notify Vincent Hallinan when they suddenly withdrew support. “My parents showed up at campaign headquarters and there was no-one there,” Ringo recalled.

Terence had told me long ago that he’d been a founder of the DuBois Clubs, which I assumed was a front for the Communist Party. “No, it wan’t a front,” Ringo said. “Terence was one of the founders. I was there, too, as the first chairman of the first club in San Francisco. Then I was chairman in Berkeley when I moved there in 1964. It was much broader than a Communist Party front. What made the DuBois Clubs attractive to some on the left was: we were the only mostly-white organization that had any African-American representation. A certain section of the left —mostly ‘red-diaper babies’— saw that as very important. The DuBois Clubs was much broader than the party, and at the same time, the party played an active role in the organization. It attracted people who never joined the party and wouldn’t have joined the party.

“The DuBois Clubs were instrumental in the civil rights movement in San Francisco. The DuBois clubs really led the Mel’s Drive-in Sit-in, which was the first mass civil disobedience in the north. And the next year it was the hotels, then automobile row. They wouldn’t hire Black people to sell Cadillacs in San Francisco. And people thought irony was dead.

“In 1965 we took part in the big three-day teach-in that led to the formation of the Vietnam Day Committee and the beginning of a real massive resistance. It was a natural progression. People who had gone to Mississippi in 1963 came back and joined the Free Speech Movement in ’64. We played a role in the huge demonstration in San Francsico that ended up in the Polo Grounds and the Youngbloods played the opening set. Kayo was really a major organizer of that, and did so through the DuBois Clubs.

“The Vietnam Day Committee organized a march down Telegraph into Oakland in ’65.The Oakland cops blocked us at the border. So the next day we marched down Adeline and they blocked us again, only this time they had the Hell’s Angels with them. The cops made way so the Angels could attack us.

“What they didn’t know was that the front of our line had been organized by the DuBois Clubs and we had some serious beef. Kayo was the Golden Gloves champion —he was a seriously tought dude. And all of us had been street fighters. And we recruited street fighters. So the Angels came through, there were about 25 of them, led by Sonny Barger, and he tried to push through Kayo and I and we both hit him at the same time and he went down on his ass. Kayo hit him with a really sweet right hand and I hit him with a left hook to the chin —I didn’t know Kayo was going to hit him—and he just went down! The bastards thought they could just beat up the peace demonstrators. They attacked this crowd of several thousand thinking we were pacifists, which we weren’t. People were clamoring to get into it with the Hell’s Angels. After about 15 seconds they realized they’d gotten into something they weren’t prepared for. If it hadn’t been for the Oakland cops, we’d have finished them off. But the cops attacked, they clubbed Terence over the head and me on the shoulder and we wound up crawling back to the Berkely lines. And Kayo says to me —while we’re on our hands and knees— ‘Ringo, you know it’s true: the cops really are the armed agents of the ruling class.’ He was funny! No matter what he was into, he was always in a slightly different place.”

I recalled that Alex Cockburn had first met Terence and Ringo on a march for nuclear disarmament in England. Ringo filled me in: “We took Alex.” It was the second Aldermaston March, 1961. “We were friends with Konnie Ziliacus, who was a member of parliament from Manchester. Alex was dating Zillie’s daughter. He had never taken part in a demonstration and we said, ‘Come on, Alex, you gotta do this.’ So he went and had a very good time, although it really rained and we all got very wet. It was three-day march ending in Trafalgar Square and overflowing into all the streets around it.”

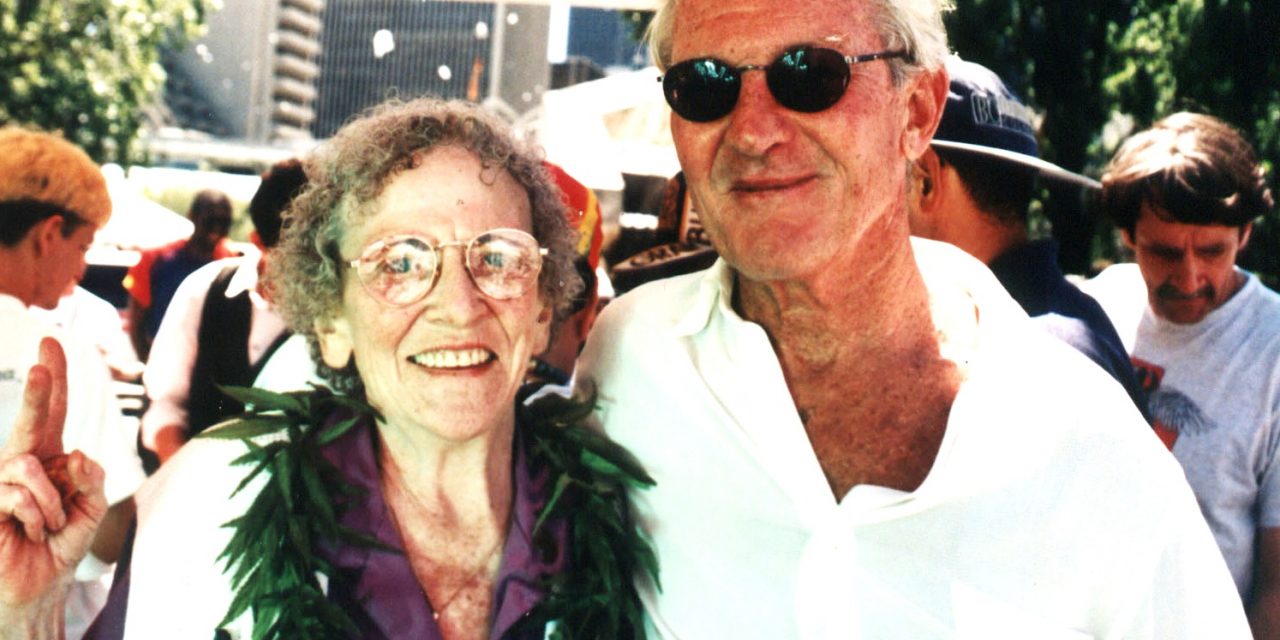

The photo is of Terence Hallinan with Mary Rathburn (“Kayo” and “Brownie Mary”)