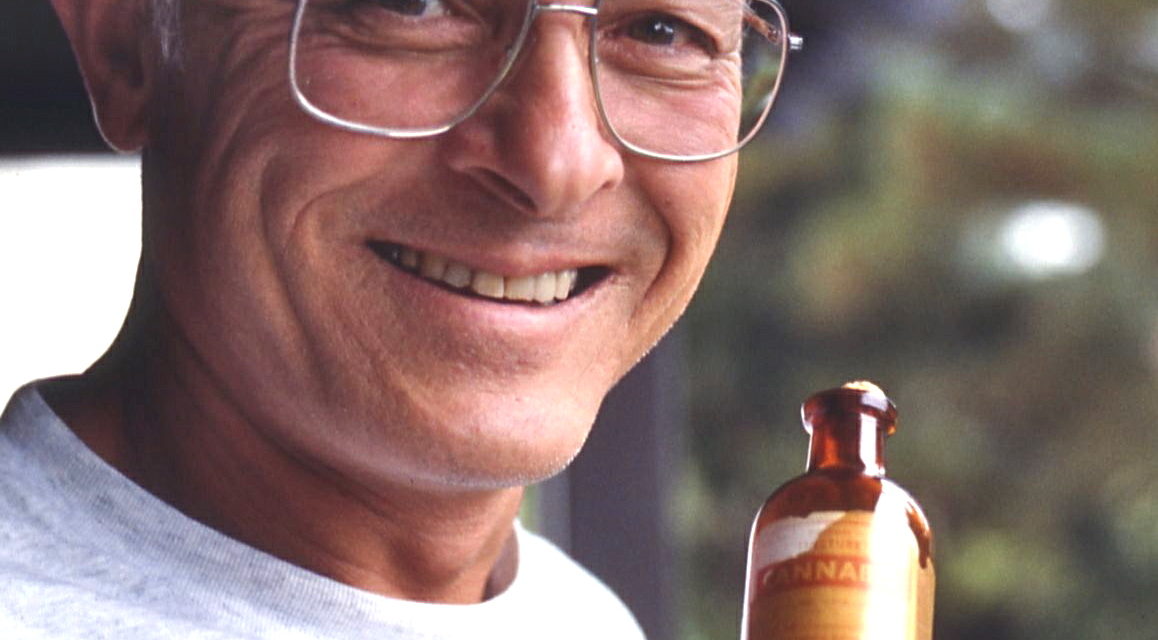

Tod Mikuriya, MD, who organized the group now known as the Society of Cannabis Clinicians, died 10 years ago this month at his home in the Berkeley Hills. He was 73. The cause was cancer, diagnosed originally in his lungs. (He had been a cigarette smoker for more than two decades. He quit in the 1970s.)

His friend Michael Aldrich said the essential thing about Tod as a physician was that “he believed his patients.”

Tod grew up in Eastern Pennsylvania. Because his father was born in Japan and his mother in Germany, he and his sisters were cruelly taunted by other kids during World War II. This interaction —being a victim of prejudice— formed him politically, he said.

He graduated from Reed College in 1956 and was drafted into the Army in ‘57. After Basic he was assigned to Fort Sam Houston, Texas, where he worked on the locked psychiatric wards. He got an early release from active duty to attend Temple University School of Medicine.

His interest in cannabis as medicine was first piqued when he read an unassigned chapter in a pharmacology textbook (Gilman & Gilman, 2nd edition). He got the hint from faculty members that it was too risky a subject to discuss.

In the summer of ‘59 Tod drove his VW bug to Mexico to conduct what he called “My first clinical experiment.” He easily scored some pre-rolled joints from a “street entrepreneur” and, being a cigarette smoker, had no problem inhaling. He experienced “a rush of ideas and images,” which, being a med student, he wrote down. He smoked the rest of his stash with two friends from Reed in Mexico City. In a “group context,” he noted, cannabis was “easier to control than alcohol and, relatively speaking, no big deal.”

He then didn’t smoke any for five years.

He did his internship at Southern Pacific Hospital in San Francisco and began a residency in psychiatry at Oregon State Hospital in Salem. He thought Freudian psychanalysis, then in vogue, was a cult. A neighbor reintroduced him to cannabis. He finished his residency at the Mendocino State Hospital, where the staff introduced him to psychedelics.

He applied for a job at the Institute near Princeton, New Jersey, where Humphrey Osmond —who had given mescaline to Aldous Huxley— was studying the effects of psychedelic drugs. Tod worked with heroin addicts. Osmond, who unbeknownst to Tod had CIA connections, steered him to a job with a prestigious title at the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington: “Director of Non-classified Marijuana Research.”

Tod soon realized that NIMH was giving grants to researchers looking for adverse effects and better methods of detecting marijuana users. He wrote a six-page, single spaced “Position Paper on Marijhuana” stating that the herb was not addictive and its use should not be criminalized. His recommendations were ignored.

But Tod made good use of his time in Washington, reading and photocopying cannabis-related material from the National Library of Medicine. He was compiling a master bibliography of writings on the subject, and trying to locate the texts themselves for his own education and for inclusion in an anthology that would be useful to physicians.

In late 1967 NIMH sent him to the Bay Area to gather intelligence, he realized, on the counter-culture. He defected and moved here forthwith. His first employers were the Alameda County Alcoholism Clinic and the state Department of Rehabilitation.

One of his patients was a 49-year-old alcoholic who had made her life manageable by using cannabis to cut down on drinking. Tod made her the subject of a paper, “Cannabis Substitution: An Adjunctive Therapeutic Tool in the Treatment of Alcoholism.” It is an extended case report, more than 50% dialog, with Tod asking about dose and price and effect and the patient providing details like, “I wasn’t bothered by little things that are unimportant, which when you are drinking are greatly magnified.” The paper appeared in a now defunct publication, Medical Times (April 1970, pages 187-191).

Also in 1970 Tod began a 21-year stint as an attending psychiatrist at Everett A. Gladman Memorial Hospital in East Oakland. Pro-cannabis activists were among his closest friends —Mike and Michelle Aldrich, Gordon Brownell, Pebbles Trippet, Dennis Peron and Jerry Mandel to name a few. He campaigned for California’s original legalization initiative —Prop 16, which one-third of the voters supported in 1971— and for years he was on the board of NORML. But given Prohibition, cannabis could play no role in his practice.

Fast forward to 1990 and Dennis Peron launching of the San Francisco Cannabis Buyer’s Club in response to the AIDS epidemic. “A unique research opportunity” is how Tod saw the club.

Dennis had drafted and successfully campaigned for Proposition P —a request by San Francisco voters that “Licensed physicians shall not be penalized for or restricted from prescribing hemp preparations for medical purposes to any patient.” Prop P passed by a 4-to-1 margin and the city supervisors passed a corresponding resolution that Dennis would cite as “the authority by which the buyers club will supply cannabis to those who can benefit by it.”

Tod drafted an intake protocol for the club — a letter of diagnosis from a licensed physician was the key requirement (which Dennis would waive for applicants 65 and older). Tod also arranged to interview members. The result was a formal paper that Tod eventually posted online, “Cannabis Medicinal Uses at a ‘Buyers’ Club.” It was based on data from 57 SFCBC members (41 HIV+). They reported using for multiple purposes:

“Anorexia/nausea/vomiting/diarrhea 39, anxiety/panic attacks/depression 39, AIDS related illness (wasting) 35, arthritis and other pain 22, muscle spasm 19, harm reduction: alcohol substitution 12, opioid substitution 6, amphetamine substitution 1, followed by migraine/vascular headache 11, cancer/cancer chemotherapy 10, asthma/cough 9, itching/hiccough 8, epilepsy 5, glaucoma 4, drusen of the optic chiasm 1, post-traumatic stress disorder 1, and pre-menstrual syndrome 1.”

Tod concluded: “Cannabis is not a new drug. Medicinal applications reported by self-medicating buyers would appear to reconfirm descriptions in clinical literature before the drug was removed from prescriptive availability. Further clinical study is warranted. Restoration of cannabis to prescriptive availability is indicated.”

Membership in the Cannabis Buyers Club grew steadily in the early ‘90s as people with conditions other than AIDS joined. Tod continued interviewing members and updating his master list of conditions treated successfully with cannabis.

The Run-up to Prop 215

“The movement that had been asleep for 20 years woke up when the medical dimension emerged on the scene,” says Pebbles Trippet. Activists using Dennis’s club as their informal headquarters helped draft and lobby for medical-marijuana bills introduced in 1994 and ‘95 by State Senator John Vasconcellos (D. Santa Clara). Both times the bills were whittled down by the legislature to apply only to patients suffering from AIDS, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and glaucoma. And both times the bills were vetoed by Republican Governor Pete Wilson.

“It’s a good thing Wilson vetoed those bills,” says Trippet, looking back.

Dennis and his allies responded with a ballot measure that would legalize marijuana for medical use and could not be vetoed or legally altered by politicians in Sacramento. Dennis and Dale Gieringer of California NORMLwrote a first draft in July ’95. It was revised in extended discussions that included Dennis’s lieutenant John Entwistle, attorney Bill Panzer, Tod, Valerie Corral expressing the growers’ POV, and others offering their suggestions.

There was consensus among the drafters that the bill should protect all medical users. Mikuriya suggested wording that conferred protection not just on cannabis users treating certain specific illnesses but on those treating “…any other illness for which marijuana provides relief.”

The Value of Clinical Evidence

Instead of dismissing what patients were telling him about their cannabis use as skewed by the placebo effect or “drug-seeking behavior,” Mikuriya assumed that people were providing accurate information. In the conventional doctor-patient relationship, he liked to point out, the patient conceals illicit drug use. With a cannabis consultant, the patient can level.

Mikuriya extracted data from patients’ reports: what symptoms they were seeking to alleviate, with what types of cannabis, using what delivery system, to ingest what dose, how frequently, with what results… He based his landmark papers on Cannabis as a Substitute for Alcohol, Cannabis in the Treatment of PTSD, and Cannabis as a First-Line Treatment in Childhood Mental Disorders on clinical evidence.

MORE TK -Meeting the mailchimp deadline, Fred Gardner