published by Nation Books, 2009; 209 pages, $16.95 (paper)

Reviewed by Bob Jameson

Initially this book lost me at the very title. I kept reading because Rick Steves is an experienced and insightful guide and over the years I have enjoyed and learned much from his travelogues. I just have difficulty accepting the premise that leisure travel or tourism can be considered a valid political act, even loosely defined.

I have travelled extensively, sometimes for years at a time, and I have had some incredible experiences while traveling. My world view has definitely been widened through travel, and I always try — as Steves advises his readers— to get a true flavor of whichever country I have been lucky enough to visit. I just cannot see those travels as being in any way a political act.

However people travel, however light the footprint, however green the credentials, the bottom line, in my opinion, is that leisure travel is a truly hedonistic act. It is a pastime affordable only to those with disposable income and leisure time to burn. Add to that the cost to the environment of burning jet fuel and we have got off to a very bad start indeed.

Travel as a Political Act is not a travel guide, like, for example, Rick Steves’ Amsterdam —a thorough, comprehensive book that is close to my heart. I spent a glorious long weekend in that city just last year with my wife and her parents and Rick Steves as our mentor. In a city with over two hundred ‘coffee shops’ to choose from and only three days in which to check them out, Steves had already done the hard legwork for us by cherry picking a selection of his favorites. I can most definitely vouch for the quality of his choices.

Travel as a Political Act is based on a lecture Steves has been giving in recent years. It is a collection of his insights born from a career based around travel and a hefty chunk is devoted to pointing out how the Dutch approach towards cannabis has actually lowered the consumption rate amongst the Dutch people – while the draconian approach of the UK and US government has had the opposite effect. Steves shows that giving adults informed and legitimate choices allows them to make truly personal decisions, rather than those based on a mixture of peer pressure and the ‘forbidden fruit’ syndrome. In the Netherlands this approach —not the threat of prison— has resulted in fewer long-term cannabis users. And removing the burden of enforcement allows the Dutch police force to focus attention on more serious criminal activities.

It takes great courage for a mainstream travel writer with corporate book and TV contracts to pen so positively and informatively about cannabis and other political issues. For anyone who uses cannabis either for recreational or medicinal purposes, a visit to Amsterdam is a true eye-opener. A tantalizing glimpse of how it could and should be at home, too.

I have traveled to many of the same places as the author and even during the same time frame on occasion. I was in El Salvador in 1988 and likewise found the experience to be profound. It was a time of intense repression in the country as the rightwing military junta imposed curfews, allowed its death squads to operate unchecked and committed many other violations of human rights against its populace.

One afternoon in San Salvador I had stayed out a little too late and missed the last bus back to my hotel before the 6 p.m. dusk curfew. As I wondered at my chances of getting back without running afoul of the authorities, I heard a tapping noise near my ankles. A man was knocking on the glass of a basement window and furiously beckoning me to come inside. I looked in and saw that it was a club of sorts, there was a bar, a live band and a lot of people in that basement.

I knocked on the door and was ushered inside by the guy who had been tapping on the street-level window. My new friend explained that because of the curfew, San Salvadorians start a night out at sundown and party until dawn. And party they did. It was one of the best nights of my life, and a fine lesson that the human spirit is incredibly resilient. Even in the face of extreme subjugation, people want to find some enjoyment in life, where they can.

I pushed on reading and I am very glad I persevered. Steves draws upon his many years of travel experience and accumulated knowledge of the world to offer numerous historical and cultural perspectives from around the globe. These are threaded through the book and woven together to show how similar human beings are across the board, despite geographical and cultural differences.

When on the Bay of Kotor, in Croatia, Steves takes a boat ride to an island in the middle of the bay. Legend has it that the small island was made by fishermen who had seen the Virgin Mary in the reef and placed a stone in that spot every time they passed by, eventually building up the island. There is an old church on the island. In the church hangs a piece of embroidery, showing the Blessed Virgin surrounded by angels. It took a local woman 25 years to sew, 200 years ago. It is an exquisite piece of work made from silk and other fine materials. She even incorporated her own hair and the angels’ hair in the embroidery turns white as her own hair turned white. It is a fine illustration of how people bring meaning to life by producing and contributing and co-operating. And that the desire to revere and honor that which we hold dear and believe in is a deep-seated human trait, shared by all cultures.

Steves has a genuine desire to try and change the mindset of those people who never leave the supposed safety of the “Homeland” and who rely on a heavily biased media for their world view. He would also change the mindset of the insular tourist —the type of tourist who never leaves the confines of the resort, unless on an organized excursion. The type of tourist who tries to avoid the resident population at all cost, who chooses egg and chips and draft Fosters lager over local food and drink. Steves’ premise is that direct experience of another culture —travelling on local public transport, for instance— and having genuine interactions with local people helps dispel the xenophobic myth of home supremacy.

A worthy goal for sure, but the cynic within me remains skeptical. I just do not think we need to find any more reasons to travel or make us feel better about our traveling. What we may need to find instead are ways of curbing our desire to travel so much. And when we do travel, to find greener means to get around. If people could be persuaded to travel less frequently but for longer periods of time this would reduce somewhat the impact of leisure-based air travel.

I have seen at first hand the damage that can be inflicted by mass travel. A quarter century ago, in my long-haul travel days, I would happily journey for many days on crowded buses or boats or even hike for days if needs be to reach inaccessible and remote destinations. In experiencing something that only those travelers with time and determination could, I felt that I was somehow ahead of the curve. But a few years later I realized that first-wave travelers are really scouts, ultimately calling in the subsequent deluge of mass transit tourism; paving the way for the new airport or fresh scar of tarmac that makes such places accessible to the two-week travel brigade.

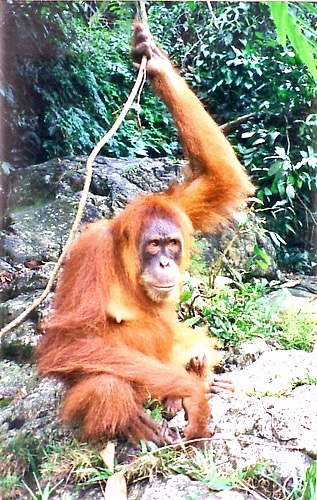

In 1986, I travelled to Bukit Lawang, an orangutan sanctuary in Northern Sumatra. At that time it was quite a mission and visitors to the park were limited. A single-entry, date-specific visa had to be obtained in the capital, Medan, followed by a bone-shaking nine-hour ride on a very crowd-ed and rickety old public bus. For the last 30 miles there was no road to speak of at all, just a pot-holed and deeply rutted muddy track through the jungle. In Bukit La-wang itself there were about 20 houses and a solitary, family-run guest house, sited right next to the babbling Bohorok river. It was a slice of paradise, set in virgin rainforest on the edge of the Gunung Lesser national park.

In 1986, I travelled to Bukit Lawang, an orangutan sanctuary in Northern Sumatra. At that time it was quite a mission and visitors to the park were limited. A single-entry, date-specific visa had to be obtained in the capital, Medan, followed by a bone-shaking nine-hour ride on a very crowd-ed and rickety old public bus. For the last 30 miles there was no road to speak of at all, just a pot-holed and deeply rutted muddy track through the jungle. In Bukit La-wang itself there were about 20 houses and a solitary, family-run guest house, sited right next to the babbling Bohorok river. It was a slice of paradise, set in virgin rainforest on the edge of the Gunung Lesser national park.

In 1997 my younger sister visited Bukit Lawang and it was a totally different story. The road had been paved the whole way in and tourism was running almost unchecked. The journey time from Medan was cut to under four hours on a shiny private tourist bus and entry to the park was rubber-stamped on arrival. As long as you paid the fee you could now stay as long as you wanted. There were more than 20 guest houses and hotels and more than a hundred kiosks. Some of the buildings were three and four stories high.

In 2003, flash floods, caused by the clearance of the jungle to raise more revenue and accommodate yet more (“eco!”) tourism, wiped out the entire site, including 400 houses, three mosques, 280 kiosks and food stalls and 35 inns and guest houses. The disaster claimed more than 200 lives.

Leisure travel is still restricted to a small minority of the global population.

Capitalism drives globalization hard and tourism has been a powerful tool within that machine. It is the showy edge, the success story of the capitalist dream. “Look at me, I have so much accumulated wealth that I can afford to take a break from work and spend my excess money in your country.” It is a strong motivator. One can easily understand why poorer countries aspire to raise living standards to the level of those of the wealthy tourists who visit and, even with the best of intentions, flash the cash.

We need to remember that even today, leisure travel is still restricted to a small minority of the global population. How will the planet fare when the emerging middle classes of India and China have the means to enjoy what their Western counterparts have long taken for granted? What will happen when another billion or more people expect to take annual vacations abroad?

Maybe the values that Rick Steves tries to engender in this book —respecting the people of other nations for who they are; accepting and learning from cultural differences— will help us find a balance and make the necessary political transition.

Travel as a political act? I am still not fully convinced. Read this thought-provoking book? Definitely.

Bob Jameson runs a plumbing supply business in Los Angeles.

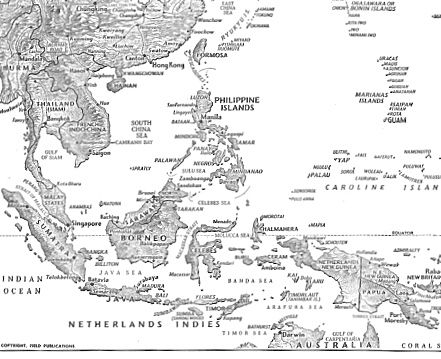

MAP OF SOUTHEAST ASIA at the end of World War Two from “A Guide to the Peace” (Welles, ed., Dryden Press, NY, 1945). Bukit Lawang is in Northern Sumatra, which was then part of the Dutch colonial empire. In the postwar years the U.S. took over political and military “responsibilities” of the Dutch, French, British, and Belgian administrators.

MAP OF SOUTHEAST ASIA at the end of World War Two from “A Guide to the Peace” (Welles, ed., Dryden Press, NY, 1945). Bukit Lawang is in Northern Sumatra, which was then part of the Dutch colonial empire. In the postwar years the U.S. took over political and military “responsibilities” of the Dutch, French, British, and Belgian administrators.