Employer’s Right to Fire Workers Supercedes State Law, Says California Supreme Court

By Fred Gardner

The boss’s sacred right to fire a worker supercedes the worker’s legal right to fire up a medicinal herb in his own house on his own time, the California Supreme Court has ruled in the case of Ross v. RagingWire. To reach this conclusion the Court had to violate its own impeccable logic in People v. Mower, a 2002 ruling that defined physician-approved cannabis users as “no more criminal than” prescription-drug users.

Discrimination by employers has been, arguably, the single biggest factor limiting implementation of Prop 215 in the years since its passage. Countless thousands of California workers have been fired, or threatened with termination, or not hired in the first place because they tested positive for marijuana. Millions more won’t consider marijuana as a treatment option for fear that it could cost them their jobs.

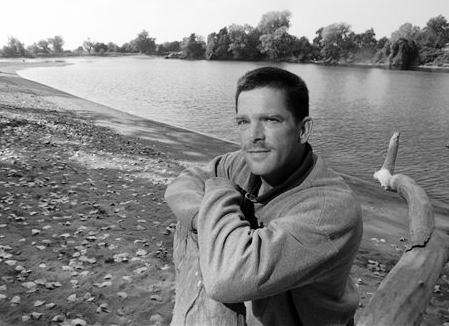

Gary Ross, now 45, got injured while in the Air Force in 1983. While he was working on a plane he fell and landed directly on his tailbone, breaking several transverse processes in his lower back. His service-connected disability qualified him for vocational rehabilitation. He trained in the computer field and became successful over the years as a systems administrator.

Veterans Administration doctors put Ross on a series of pain-killers. “Soma was popular for a while until they found it highly addictive and took it away,” he says. “Flexoril. Valium. Percocet. Demerol. Vicodin.” In 1999, concerned about the side-effects of high doses of Vicodin (which is hydrocodone and Tylenol), Ross went to see Tod Mikuriya, MD, and got an approval to medicate with marijuana.

In 2001 Ross was hired by Raging-Wire Telecommunications of Sacramento. He presented his approval letter from Dr. Mikuriya at a pre-employment drug test and notified RagingWire’s human resources department that he used marijuana only when off-duty and not at the work site.

After Ross tested positive, Raging-Wire fired him. He sued for discrimination, arguing that he had been using legally under California’s Health & Safety Code. He had a documented disability and a doctor’s approval; he smoked at home in the evening; he neither used nor was impaired at the workplace. RagingWire argued that it had a right to fire Ross for testing positive because federal law prohibits all marijuana use.

The Sacramento Superior Court and the Third Appellate District Court ruled for RagingWire. Ross took his case to the California Supreme Court, represented by Sacramento defense specialist Stewart Katz and Joe Elford of Americans for Safe Access.

Ross stated a claim under California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) which bars employers from firing workers for “physical disability” or “medical condition,” and obligates them to make “reasonable accomodation” for disabled employees. The accomodation Ross sought was a waiver of Raging-Wire’s requirement that employees test negative for marijuana.

Ross also cited the law created by SB420, which states that “Nothing in this article shall require any accomodation of any medical use of marijuana on the property or premises of any place of employment or during the hours of employment.” The five co-authors of SB420 supported Ross with an amicus brief saying that their bill was based on the assumption “that the FEHA does require employers generally to accomodate off-duty, off-premises medical cannabis use by their employees, absent an undue hardship.”

Werdegar opined that the legislature as a whole did not share this assumption, i.e., did not know what they were voting for when they passed SB420. “Amici do not assert,” wrote Werdegar, “that they shared their view of the proposed legislation with the Legislature as a whole. We therefore have no basis for imputing the authors’ views to the whole Legislature.”

Ross’s second claim was based on the principle that an employer may not discharge an employee for a reason that violates a fundamental public policy of the state. For example, bosses can’t fire people —legally—because of their gender or race. Ross’s lawyers argued that RagingWire violated the policies implicit in the Compassionate Use Act and the privacy clause of the California Constitution (a worker should be able to choose his or her own medical treatment without interference from his or her boss).

On Jan. 24 a 5-2 majority issued its judgment for RagingWire. It was written by Justice Kathryn Mickle Werdegar, who should know better —her husband, David Werdegar, MD, used to run San Francisco General Hospital.

Werdegar’s key point was that the voters, in passing Prop 215, never

“intended… to change employment law.” Since there was nothing in Prop 215 itself suggesting that voters did not want medical-marijuana users to have the same rights in the workplace as, say, Zoloft users or insulin users, Werdegar cited the ballot arguments written in support of Prop 215: “The proponents… described the proposed measure to the voters as motivated by the desire to create a narrow exception to the criminal law.”

The proponents she refers to are/is Bill Zimmerman, the campaign manager installed by East Coast masterminds to replace Dennis Peron as their price for funding a signature drive. Zimmerman wrote ballot arguments pitching the initiative as merely a defense in court, not a bar to prosecution. Werdegar pointedly quotes Zimmerman’s line that “police officers can still arrest for marijuana offenses. Proposition 215 simply gives those arrested a defense in court.”

She concluded: “given the Compassionate Use Act’s modest objectives and the manner in which it was presented to the voters for adoption, we have no reason to conclude the voters intended to speak so broadly, and in a context so far removed from the criminal law, as to require employers to accomodate marijuana use.”

Attorney Bill Panzer says that the state Supreme Court ruling for RagingWire “brings to mind my old law school professor who used to say, ‘No case is ever decided on the law. First the judges decide what they want to do. Then they find the reasoning. The reasoning here, distilled down, is ‘Just because it’s not illegal doesn’t mean it’s legal.’To which I answer: ‘Yes, it does.’”

The Ross case “came down to the state-federal conflict,” says Panzer, “and the state Supreme Court chickened out.”