The “Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act,” drafted by Ron Wyden of Oregon and Cory Booker of New Jersey, was introduced on July 14 in the US Senate by Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. The measure would remove marijuana from the Controlled Substances Act, allow banks to handle marijuana-related money, and expunge non-violent marijuana-related federal arrests and convictions. Funds would be directed to uplift communities most damaged by years of prohibition. (Happy Bastille Day, America!)

According to the NY Times story by Nick Fandos, “The legislation faces an uphill battle in the Senate, where Republicans are opposed, and it is unlikely to become law soon. President Biden has not endorsed it, and some moderate Democrats are likely to balk at the implications of decriminalizing a drug that has been policed and stigmatized for so long.”

Schumer vowed “to use my clout as majority leader to make this a priority in the Senate.” He told the media, “It’s not just an idea whose time has come —it’s long overdue.” Overdue, indeed, and probably too late for the Democratic Party to “own” the obviously popular issue. The Times piece quoted a conservative think tanker who supports drug-law reform: “The culture war over this issue has definitely moved on. Even among Republicans, you’re getting very close to a majority supporting legalization outright.”

The Democrats had their chance handed to them when California voters legalized marijuana for medical use in 1996 —on the same day that Bill Clinton was re-elected. If only the Big Triangulator had said, “The people of California have sent the government a message: they want to allow the medical use marijuana. We are very concerned about the effect on public health and safety, so we will be carefully monitoring the impact of this new state law…” In due course the Democrats would have been seen as the party that allowed the end of marijuana prohibition. Instead, Clinton closed down the leading California dispensaries in ’97. He did it by civil injunction, the tactical hypotenuse between siccing the DEA on them and allowing them to operate.

Al Gore would have won handily in 2000 if instead of the “more research is needed” line he had supported states’ rights to regulate marijuana as they saw fit. There would have been no hanging chads.

(BTW, Gore had been a heavy user. What hypocrites these politicians be!)

US Overdose Epidemic Escalates

Puns are commonplace in marijuana-related headlines. “Drug Overdose Deaths Spike” in the New York Times July 14 was the first I’d seen making light of needles. According to the story by Josh Katz and Margaret Sanger-Katz, “As Covid raged, so did the country’s other epidemic. Drug overdose deaths rose nearly 30 percent in 2020 to a record 93,000, according to preliminary statistics released Wednesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s the largest single-year increase recorded. The deaths rose in every state but two, South Dakota and New Hampshire, with pronounced increases in the South and West.

“The pandemic itself undoubtedly contributed to the surge in overdose deaths, with disruption to outreach and treatment facilities and increased social isolation. Overdose deaths reached a peak nationally in the spring of 2020, in the midst of the pandemic’s most severe period of shutdowns and economic contraction. But public health experts said there had been a pre-pandemic pattern of escalating deaths, as fentanyls became more entrenched in the nation’s drug supply, replacing heroin in many cities and finding their way into other drugs like meth.”

The reporters pointed out that President Biden had just appointed to “the post sometimes called the drug czar,” Dr. Rahul Gupta, former commissioner of public health for West Virginia, “a state with one of the sharpest rates of increase in drug deaths last year.”

In the not-so-distant past, the Drug Czar (the official title is Director of the White House Office on Drug Policy) was the visible face of marijuana prohibition. Poppy Bush’s Bill Bennett and Clinton’s Barry McCaffrey and W.’s John Walters and John Ashcroft both fought in federal court to disimplement California’s Compassionate Use Act of 1996. Reformers saw them as arch foes. The pharmaceutical industry stayed discreetly in the background while the ONDCP promoted its interests.

Also, in the not-to-distant-past, I would end an item like this by pointing out that not one of the 93,000 “drug deaths” reported in the Times had been caused by marijuana. But now that I’ve declared war on the United States of Amnesia, I’ll end with the relevant background.

The Importance of Conant v. Walters

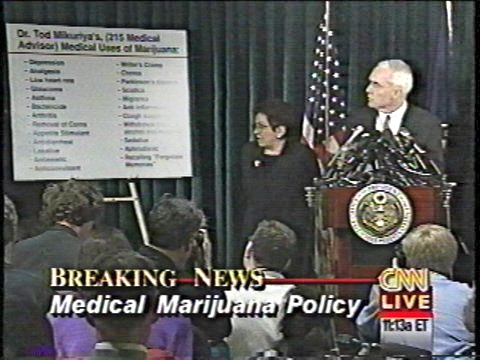

Weeks after California voted Yes on Prop 215, the feds tried to disimplement the new law by threatening to revoke the license of any doctor who actually approved marijuana use by patients. The threat to doctors was announced by McCaffrey at a press conference carried live by CNN Dec. 30, 1996. Flanked by Attorney General Janet Reno, Alan Leshner of NIDA and Donna Shalala of Health & Human Services, the Drug Czar dismissed medical marijuana as a “Cheech and Chong show” and mocked as absurd Tod Mikuriya’s claim that this one substance could alleviate a vast range of symptoms.

Within weeks, lawyers funded by Ethan Nadelmann (whose Drug Policy Alliance was then called the Lindesmith Center) filed suit in federal court to enjoin the feds from carrying out their threat. The lead plaintiff was Marcus Conant, MD, and the case was called Conant v. McCaffrey. Conant was a perfect choice because he was a UCSF Professor of Dermatology and had worked with AIDS patients whose symptoms included Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Nadelmann saw to it that Dr. Mikuriya was not included among the many co-plaintiffs, although it was Mikuriya who had helped draft Prop 215 and whom McCaffrey had dissed and threatened by name.

In March ’97 a federal judge named Fern Smith —a Reagan appointee!— granted Conant et al their injunction on Constitutional grounds. The doctor-patient conversation, she reasoned, is protected by the First Amendment’s freedom-of-speech guarantee.

“A minor slight,” is how Tod described being excluded from the Conant suit. He was more dismayed by the DPA “pulling all their resources out of California to promote the master plan,” i.e., to pass medical marijuana laws, no matter how restrictive, state-by-state, until so many had been enacted that the federal government would have to accede somehow. Tod called Prop 215 “a unique research opportunity” and thought the movement’s most important task was to document the safety and medical efficacy of cannabis —a job for clinicians and epidemiologists, not campaign consultants and public relations experts.

Was Cannabis First Grown in China?

In a paper published July 16 in Science Advances, Guangpeng Ren and colleagues conclude from genetic-sequencing data that all Cannabis Sativa comes from a “single ancestral gene pool” and was probably domesticated about 12,000 years ago in Eastern China for fiber and medical use. Breeding for psychoactivity probably began some 4,000 years ago as cannabis was spreading to the Middle East and Europe, according to Ren et al.

Mike Ives’s story summarizing the new study in the NY Times had a lede we’ll give an A for effort: “People feeling the effects of marijuana are prone to what scientists call ‘divergent thinking,’ the process of searching for solutions to a loosely defined question. Here’s one to ponder: Where did the weed come from?”

In my experience people feeling the effects of marijuana are prone to searching for their glasses and/or the remote.