In 1967, the year Terence “Kayo” Hallinan was sworn in as a lawyer, thousands of young people would come to San Francisco for the “Summer of Love” and many thousands more would go to Vietnam. The number of US troops there would exceed half a million by ’68. Terence had an office in a family-owned building on Franklin Street, a block from City Hall, with a good law library, a skilled staff, and brother Patrick upstairs. His fight to get admitted to the bar had kept his name in the news and he had no dearth of clients. He defended sex workers, drug dealers and their customers, student activists, and artists in the counter culture. Whereas some San Francisco lawyers were seen as “left” politically, and others were seen as “hip” with respect to sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll, Terence was seen as both. He had the best marijuana, dated Janis Joplin, and was national secretary of the DuBois Clubs, a youth group with loose ties to the Communist Party.

One episode from this period has a cosmic (as they used to say) connection to our pandemic present. Among Terence’s diverse clientele were the Diggers —quasi-political performance artists who staged small-scale food giveaways and poetry readings. The media was impressed by their swashbuckling leaders and they were credited with sheltering the runaways who were streaming into the city. (The real sheltering was organized by two un-famous Diggers, Arthur and Jane Lisch, and funded by the American Friends Service Committee.) In May ’68 Mayor John Shelley, responding to complaints of profanity, ordered a halt to lunchtime poetry readings on the steps of City Hall. After a speech by Terence describing their noble intentions, the Diggers staged a City Hall poetry reading on May 7. The looming confrontation had been well publicized and several hundred people —mostly workers on their lunch break— watched as and five Diggers were arrested, including one for wearing a shirt seemingly made from the American flag, another “who shouted a four-letter word meaning to make love” (to quote the Chronicle),and Ron Thelin for wearing a bandana as a mask. Muni Court Judge Albert Axelrod, returning from lunch, told the media that the Penal Code made it a crime “to appear in any street or highway or in other public places with his face partially or completely concealed by means of a mask of other regalia or paraphernalia, with intent to conceal his identity.” Thelin, a former Eagle Scout and an Army veteran said that he wore the mask to “to intellectualize my fantasy, which is to be free.”

Between the time of the mask-in bust and Thelin’s appearance in court, Terence had been clubbed in the head by SFPD officer Michael Brady and required 16 stitches. This occurred one night at San Francisco State, where students were staging a sit-in at the President’s office demanding an end to ROTC and the creation of Black and Hispanic studies programs. Terence represented the 450-member Associated Students and was at the scene when the police tried clear out the demonstrators. He came to the defense of a young woman who had been knocked down and was charged with assault. “They’ll put me on trial and I’ll put the San Francisco police on trial,” he said, describing officer Brady as “a well known sadist.” Represented by his father, Terence filed suit for half a million dollars and settled for $10,000. On May 23 he appeared in Municipal Court on Ron Thelin’s behalf, with his brow neatly bandaged, and got the absurd charge dismissed.

Terence did not stop operating as a political organizer when he became a lawyer. His role and the DuBois Clubs’ role in promoting opposition to US intervention in Vietnam has been under-acknowledged. In July 1966 DuBois Club member Dennis Mora and two GIs he had trained with at Fort Hood, James Johnson and David Samas, announced at a press conference in New York that they were refusing orders for Vietnam. The DuBois Clubs backed them in a suit against Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara challenging the legality of the war. Although there had been a number of individual acts of refusal by active-duty military personnel, the Fort Hood 3 were the first to act collectively. Mora was Puerto Rican, Johnson was black, and both were from Harlem; Samas was a gringo from Bakersfield (who would eventually become a master upholsterer in Fort Bragg). They drafted a joint statement that said, “We will not be a part of this unjust, immoral, and illegal war.” In an individual statement Samas noted that the Nuremberg Trials established a soldier’s right to refuse illegal orders. “The way I was brought up,” he added, “was to judge things with my conscience, and that is what I did.” Mora was sentenced to three years at Leavenworth. Samas and Johnson got five year sentences, reduced to three years on appeal; they were released after 28 months.

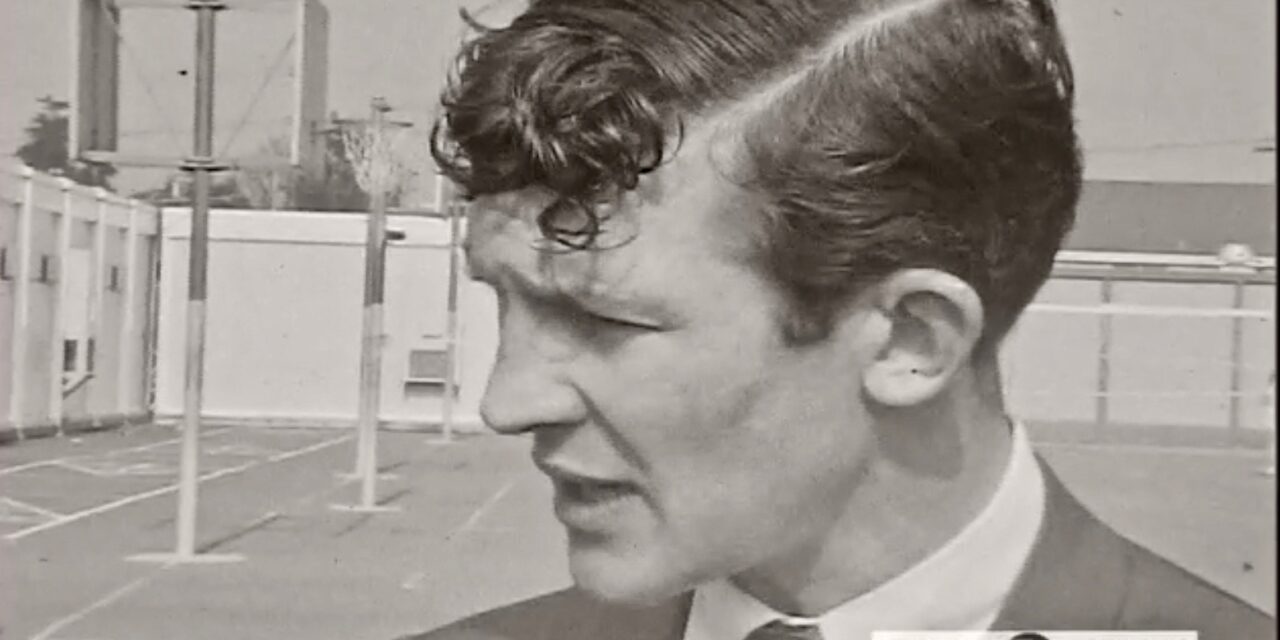

In September ’67 Hallinan represented Ron Lockman, an African American GI who was refusing to ship out from Oakland. Lockman was a member of the DuBois Clubs from Philadelphia. Hallinan arranged for him to turn himself in at 6th Army headquarters at the Presidio of San Francisco and organized a rally in Lockman’s support on the eve of his court martial. KTVU sent a reporter to the rally. Asked if Lockman had any chance of success at his upcoming court martial, Hallinan replied like an old-timer, “Well of course any lawyer has to go into a case thinking there’s a chance he can win. There is a chance here that we can win —perhaps if there’s enough opposition and enough protest mobilized, perhaps the army will find a way to let him out on some technical basis.” Lockman’s mother was asked for a comment. (She had flown out to the Bay Area to support her son.) She said, “His fight is not in Vietnam, it is right here. Or back home in Philly where he belongs.”

The DuBois Clubs had distributed a leaflet quoting Lockman: “I’m following the Fort Hood 3. Who will you follow?” They also made pins with a picture of Pvt. Lockman in his garrison cap and the words “He won’t go! We won’t go!” Lockman’s court martial on November 13 drew a standing-room only crowd and took all of 11 minutes. The Dubois Clubs had flown in Stanley Faulkner, the lawyer who represented the Fort Hood 3, and Terence could only listen as Pvt. Lockman was found guilty of refusal to obey a lawful order, dishonorably discharged, and sentenced to two-and-a-half years at Leavenworth. (He could have gotten five years.) The Associated Press reported, “The private’s mother and his girl friend sat by him in tears. The mother collapsed briefly after hearing the sentence… Violent confrontations between civilian spectators and military policemen marked the one-day trial… The courtroom uproar and a noisy demonstration outside had erupted as the trial counsel passed around the formal charges. Seven of the outside demonstrators were arrested and charged with trespass. No arrests were made in the courtroom but six spectators were ejected by military police.”

On the day Ron Lockman was court-martialed, four US Navy enlisted men assigned to the aircraft carrier Intrepid announced through a Tokyo-based peace group that they had sought refuge in Japan. Anti-war sentiment within the ranks would keep manifesting itself in myriad ways as the US role escalated. Oakland being the main departure point, many Bay Area lawyers became familiar with the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

In July ’68, the “Nine for Peace” —five GIs, two Marines, a sailor and an Air Force sergeant named Oliver Hirsch— chained themselves in a San Francisco church to clergymen offering “sanctuary” from the war. Terence Hallinan negotiated a discharge for Hirsch on medical grounds. “The Air Force doesn’t exactly have a reputation for magnanimity towards dissenters,” he said at the time, “but at least in this instance they realized that there were certain people who couldn’t or wouldn’t adjust to military life and the war in Vietnam.” Some 20 other service members had used the church-sanctuary tactic to express opposition to the US role in Vietnam. All, when picked up by military police, were charged with having gone AWOL (absent without leave). But when the first GIs from the Nine for Peace were apprehended that summer and brought to the Presidio, they were charged with desertion. The much tougher policy coincided with Gen. Stanley Larsen returning from Vietnam to command the Sixth Army.

When an AWOL GI was picked up and brought to the Presidio, the commander of the Special Processing Detachment had to decide whether to hold him in the SPD barracks or confine him to the stockade. Jailing a man is more costly, entails paperwork for SPD staff, and reduces the likelihood of a quick return to their unit. The Presidio stockade was small —built as an office in 1912 and later converted to a jail designed to hold 43 prisoners at most— and the influx of AWOL GIs in 1968 was large. “Ordinarily a Special Processing Detachment is a limbo unit for men waiting on orders,” an MP explained to me at the time, “But Presidio SPD was completely full of AWOLs waiting on court-martial dates. It sometimes took a week to reissue them uniforms, and you’d have guys walking around in their Haight Street getup. And someone arrested on a Saturday night would come to chow Sunday with his hair down to his shoulders —right in the same mess hall where Headquarters Company ate, the prestige unit of the Presidio. The Provost Marshall said he wanted to ‘get rid of the country club atmosphere.’ Can you imagine? They thought AWOLs were coming to San Francisco because Presidio SPD was soft!”

A prospective client who called on Terence Hallinan that summer was Randy Rowland, an Army medic on orders for Vietnam. Rowland, who had enlisted after a year of college, was the son of an Air Force lieutenant colonel. He had been “impressed by the decency of the conscientious objectors” he met while training at Fort Sam Houston. Then, stationed at Fort Lewis, Rowland was “radicalized by the wounded soldiers” he helped care for. “Their attitude towards the war was all the same,” he recalls. “They said we were fighting on the wrong side over there.” Rowland drove down to the Bay Area with his wife Sue and worked hard drafting a Conscientious Objector application. In Berkeley he met two of the Nine for Peace who were planning to surrender after a peace march in October.

To be continued