By Lester Grinspoon, MD —O’Shaughnessy’s Summer 2003

There are many thousands of patients who currently use cannabis as a medicine. Only seven are allowed to use it legally. They are the only survivors among the several dozen patients who were awarded Compassionate Use INDs during a period of time from 1976 until 1991 when the government halfheartedly acknowledged that marijuana has medicinal properties.

This program was actually discontinued because of the exponentially growing number of Compassionate IND applications; the official reason was provided by James O. Mason, then chief of the Public Health Service: “It gives a bad signal. I don’t mind doing that if there is no other way of helping these people… But there is not a shred of evidence that smoking marijuana assists a person with AIDS.”

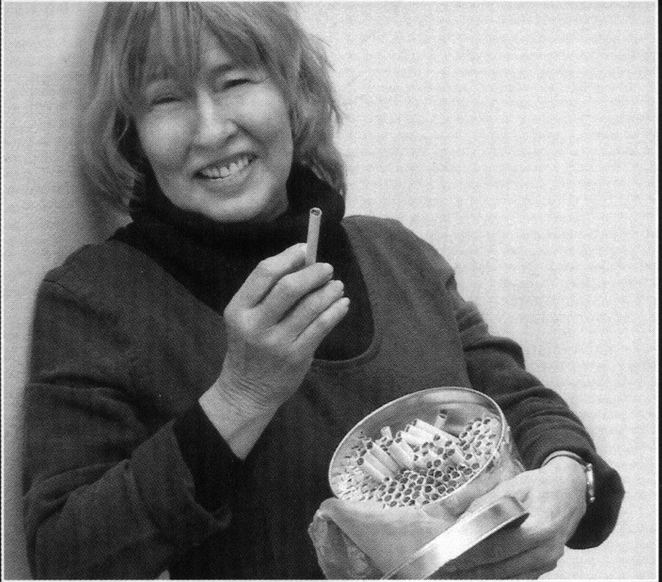

Each of the surviving IND recipients receives monthly a tin containing enough rolled marijuana joints to treat his or her symptoms for that month. Because the quality of the cannabis is poor, it requires more inhalation than a superior quality medicinal cannabis would. In fact, some of the recipients have been known to supplement this Government Issue with better quality street marijuana.

In 1985 the Food And Drug Administration (FDA) approved dronabinol (Marinol) for the treatment of the nausea and vomiting of cancer chemotherapy. Dronabinol is a solution of synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol in sesame oil (the sesame oil is meant to protect against the possibility that the contents of the capsule could be smoked). Dronabinol was developed by Unimed Pharmaceuticals Inc. with a great deal of financial support from the United States government. This was the first hint that the “pharmaceuticalization” of cannabis might be what the government hoped would solve its problem with marijuana as medicine, the problem of how to make the medicinal properties of cannabis (in so far as the government believes such properties exist) widely available while at the same time prohibiting its use for any other purpose.

But Marinol did not displace marijuana as “the treatment of choice;” most patients found the herb itself much more useful than dronabinol in the treatment of the nausea and vomiting of cancer chemotherapy. In 1992, the treatment of the AIDS wasting syndrome was added to dronabinol’s labeled uses; again, patients reported that it was inferior to smoked marijuana.

Because it was thought that it would sell better if it were placed in a less restrictive Drug Control Schedule, it was moved from Schedule 2 to Schedule 3 in the year 2000. But Marinol has not solved the marijuana-as-a-medicine problem because so few of the patients who have discovered the therapeutic usefulness of marijuana use dronabinol. In general, they find it less effective than smoked marijuana, it cannot be titrated because it has to be taken orally, it takes at least an hour for the therapeutic effect to manifest itself, and even with the prohibition tariff on street marijuana, Marinol is more expensive ($8-$10/capsule). Thus, the first attempt at pharmaceuticalization proved not to be the answer. In practice, for many patients who use marijuana as a medicine the doctor-prescribed Marinol serves primarily as a cover from the threat of the growing ubiquity of urine tests.

Cannabis Buyers Clubs

In those states, notably California, which allow for doctor-recommended use of cannabis, buyers’ clubs or compassion clubs have evolved as cannabis pharmacies for patients with appropriate physician documentation. Two distribution models have evolved. One is based on the conventional delivery system for medicine: a patient visits a buyers’ club (read: pharmacy), where he or she presents a note from a physician, certifying that the patient has a condition for which the physician recommends cannabis (read: prescription). The proprietor of the club (read: pharmacist) fills the prescription and the patient leaves to use the medicine, presumably at home. This model preserves the medical profession’s authority to decide who shall use a medicine and for how long. The pharmacy provides a source — in this case a nonprofit one— for the medicine. If the doctor and the pharmacist behave ethically, only those who have a medical need for marijuana can receive it. In turn, patients have a reliable source for the drug, relieving them of the stress of buying it on the street or secretly growing their own. The staid set-up of the club and the attitudes of the proprietors make it clear that the patient is no more expected to use his medicine there than he would be in a conventional pharmacy.

The second distribution model resembles a social club more than it does a pharmacy. The dispensing area is plastered with menus offering types, grades and prices. Large rooms are filled with brightly colored posters, lounge chairs and sofas, tables, magazines and newspapers. While some patients remain only long enough to buy their medicine, most stay to smoke and talk. There are animated conversations, laughter, music and the pervasive, pungent odor of cannabis. The atmosphere is informal, welcoming and warm, providing support for patients who may be socially isolated and have little opportunity to share concerns and feelings about their illnesses. This type of club is a blend of Amsterdam-style coffeehouse, American bar and medical support group. The model was developed and epitomized by the San Francisco Cannabis Cultivators’ Club.

Until some kind of legal accommodation makes it possible for patients to obtain marijuana without violating the law, buyers’ clubs are the best approach to the problem. Yet the federal government, including the White House, the Drug Enforcement Administration and federal law enforcement at alllevels, remains opposed to the idea. While for a short period of time after the publication of the Institute of Medicine report, “Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base,” the Feds retreated somewhat from their position that marijuana has no therapeutic value, they have been working diligently to close the cannabis clubs.

Many if not most advocates who recognize the importance of buyers’ clubs believe that the first model is preferable to that represented by the San Francisco club. The former is more businesslike, conforms more closely to the pharmacy model and at least appears to be more vigilant about checking the documentation of people who present themselves as patients. The San Francisco model club, largely because of the on-site marijuana smoking and its relaxed atmosphere, appeared to be more casual in its commitment to confirming medical need, which made even the supporters of buyers’ clubs a little nervous.

Yet the importance of the social aspect of buyers’ clubs cannot be underestimated and, in my view, offers a medically significant new model for future conventional use of cannabis as a medicine.

It is becoming increasingly clear that emotional support — contacts with and help from fellow patients, friends, family, co-workers and others — plays a salutary role in battling many illnesses. This kind of support improves the quality of life, and there is growing evidence that it may even prolong life.

In one study, socially isolated women were found to be five times more likely to die from ovarian and related cancers than women with networks of friends and families.

In another study, women with breast cancer were found to be 50 percent less likely to die in the first few months after surgery if they had confidants.

In a four-year study of 133 breast cancer patients, married women had a longer average survival time.

Researchers have consistently found that support groups are effective for patients with a variety of cancers. Participants become less anxious and depressed, make better use of their time and are more likely to return to work than patients who are given only standard care, regardless of whether they have serious psychiatric symptoms.

There is evidence that even brief supportive therapy can have benefits that last for months. Some researchers have made the controversial claim that mere participation in support groups can prolong cancer patients’ lives. The San Francisco buyers’ club functioned very much as an informal support group. It was not designed by psychiatrists and social scientists to provide supportive group therapy, but there is reason to believe it did.

One of the properties of marijuana may have contributed to its effectiveness: when people use cannabis, they tend to be more sociable and find it easier to share difficult thoughts and feelings. If there is even one kernel of truth to the idea that talking about the stress, setbacks and triumphs in the battle against an illness can help a patient cope and recover, it is clear that the San Francisco model provides the best environment for the dispensing of medicinal marijuana.

Furthermore, the existence of this kind of medical service would solve a difficult problem for the physician who recommends marijuana to a patient, particularly an older one, who lacks experience. Unlike most prescriptions which require little more preparation than providing the patient with an understanding of the possible toxic (“side-”) effects, many marijuana-naïve patients will require someone to teach them how to use it comfortably. Such instruction is readily available at a San Francisco-type facility.

Unfortunately, we live in a culture that considers such a facility a public nuisance and criminalizes a compassionate form of caring out of loyalty to a symbolic war on drugs. In any event, the present federal government is not going to allow the development of a separate distribution system, and certainly not on the San Francisco model, for this one medicine.

If the government in fact closes down the buyers’ clubs, what options are available to the many thousands of patients who find cannabis of great importance, even essential, to the maintenance of their health? They can either use Marinol, which most find unsatisfactory, or they can break the law and use marijuana.

The Government’s Problem

Why is a government which considers itself “compassionate” criminalizing these patients? What is the government’s problem with medical marijuana?

The problem as seen through the eyes of the government is the belief that as growing numbers of people observe relatives and friends using marijuana as a medicine, they will come to understand that this is a drug which does not conform to the description the government has been pushing for years. They will first come to appreciate what a remarkable medicine it really is; it is less toxic than almost any other medicine in the pharmacopoeia; it is, like aspirin, remarkably versatile; and it is less expensive than the conventional medicines it displaces.

They will then begin to wonder if there are any properties of this drug which justify denying it to people who wish to use it for any reason, let alone arresting more than 700,000 citizens annually. The federal government sees the acceptance of marijuana as a medicine as the gateway to catastrophe, the repeal of its prohibition. In so far as the government views as anathema any use of plant marijuana, it is difficult to imagine it accepting a legal arrangement that would allow for its use as a medicine, while at the same time vigorously pursuing a policy of prohibition of any other use. Yet, there are many who believe this type of arrangement is possible and workable. In fact, this is the option the Canadian and Dutch governments are presently pursuing as are various states in the U.S. Let us consider what might be involved in establishing and maintaining such a legal arrangement in this country.

The first requirement at this time is that the FDA approve marijuana as a medicine. One can argue, however, that FDA approval is superfluous where cannabis as a medicine is concerned. Drugs must undergo rigorous, expensive, and time-consuming tests before they are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for marketing as medicines. The purpose is to protect the consumer by establishing safety and efficacy. Because no drug is completely safe or always efficacious, an approved drug has presumably satisfied a risk-benefit analysis.

When physicians prescribe for individual patients they conduct an informal analysis of a similar kind, taking into account not just the drug’s overall safety and efficacy, but its risks and benefits for a given patient with a given condition. The formal drug approval procedures help to provide physicians with the information they need to make this analysis. This system is designed to regulate the commercial distribution of drug-company products and protect the public against false or misleading claims about the efficacy and safety.

The drug is generally a single synthetic chemical that a pharmaceutical company has acquired or developed and patented. It submits an application to the FDA and tests it first for safety in animals and then for clinical efficacy and safety. The company must present evidence from double-blind controlled studies showing that the drug is more effective than a placebo. Case reports, expert opinion, and clinical experience are not considered sufficient.

The standards have been tightened since the present system was established in 1962, and few applications that were approved in the early ’60s would be approved today on the basis of the same evidence. Certainly we need more laboratory and clinical research to improve our understanding of medicinal cannabis. We need to know how many patients and which patients with each symptom or syndrome are likely to find cannabis more effective than existing drugs. We also need to know more about its effects on the immune system in immunologically impaired patients, its interactions with other medicines, and its possible uses for children.

Is FDA Approval Appropriate?

But I have come to doubt whether the FDA rules should apply to cannabis. There is no question about its safety. It is one of humanity’s oldest medicines, used for thousands of years by millions of people with very little evidence of significant toxic effects. More is known about its adverse effects than about those of most prescription drugs. The government of the United States has conducted through its National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) a decades-long multimillion-dollar research program in a futile attempt to demonstrate significant toxic effects that would justify the prohibition of cannabis as a non-medical drug. Should time and resources be wasted to demonstrate for the FDA what is already so obvious?

But even if it were legally and practically possible to do the various phased studies to win FDA approval, where would the money to finance these studies come from? New medicines are almost invariably introduced by drug companies that spend many millions of dollars on the development of each product. They are willing to undertake these costs only because of the anticipated large profits during the 20 years they own the patent. Obviously pharmaceutical companies cannot patent marijuana. In fact they are very much opposed to its acceptance as a medicine because it will compete with their own products.

It is unlikely that whole smoked marijuana should or will ever be developed as an officially recognized medicine via this route. Thousands of years of use have demonstrated its medical value; the extensive government-supported effort of the last three decades to establish a sufficient level of toxicity to support the harsh prohibition has instead provided a record of safety that is more compelling than that of most approved medicines.

To impose this protocol on cannabis would be like making the same demand of aspirin

The modern FDA protocol is not necessary to establish a risk-benefit estimate for a drug with such a history. To impose this protocol on cannabis would be like making the same demand of aspirin, which was accepted as a medicine more than 60 years before the advent of the double-blind controlled study. Many years of experience have shown us that aspirin has many uses and limited toxicity, yet today it could not be marshaled through the FDA approval process. The patent has long since expired, and with it the incentive to underwrite the substantial cost of this modern seal of approval.

The only sources of funding for a “start-from-scratch” approval would be non-profit organizations or the government.

Cannabis, too, is unpatentable, so the only sources of funding for a “start-from-scratch” approval would be non-profit organizations or the government, which is, to put it mildly, unlikely to be helpful. Other reasons for doubting that marijuana would ever be officially approved are today’s anti-smoking climate and, most important, the widespread use of cannabis for purposes disapproved by the government.

To see some of the obstacles to this approach to the problem, consider the effects of granting marijuana legitimacy as a medicine while prohibiting it for any other use. How would the appropriate “labeled” uses be determined and how would “off-label” uses be monitored? Let us suppose that studies satisfactory to the FDA are somehow completed affirming that marijuana is safe and effective as a treatment for the AIDS wasting syndrome and/or AIDS-related neuropathy, and physicians are able to prescribe it for those conditions.

This will present unique problems. When a drug is approved for one medical purpose, physicians are generally free to write off-label prescriptions — that is, prescribe it for other conditions as well. If marijuana is approved as a medicine, how will off-label prescribing play out? Surely, knowledgeable physicians will want to prescribe it for some patients with multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, migraine, convulsive disorders, spastic symptoms, and other conditions for which the use of cannabis is well established by a mountain of anecdotal evidence. But what about premenstrual syndrome? Surely women who suffer from this disorder consider it a serious problem, and many of them find cannabis the most useful and least toxic treatment. What about the loss of erectile capacity in paraplegics? What about intractable hiccups? And then there is depression, not the DSM-IV defined major affective disorder, but the common low-level dysphoric condition for which general practitioners frequently prescribe SSRI’s such as Prozac? What about bipolar disorder?

Generally speaking, the more dangerous a drug is, the more serious or debilitating must be a symptom or illness for which it is approved. Conversely, the more serious the health problem, the more risk is tolerated. If the benefit is very large and the risk very small, the medicine is distributed over the counter (OTC). OTC drugs are considered so useful and safe that patients are allowed to use their own judgment without a doctor’s permission or advice. Thus, today anyone can buy and use aspirin for any purpose at all. This is permissible because aspirin is considered to be so safe; it takes “only” one to two thousand lives a year in the United States.

The remarkably versatile ibuprofen (Advil) and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can also be purchased OTC because they, too, are considered very safe; “only” 10,000 Americans lose their lives to these drugs annually.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol), another useful OTC drug, is responsible for about 10 percent of cases of end-stage renal disease.

The public is also allowed to purchase many herbal remedies whose dangers and efficacies have not been well determined. Compare these drugs with marijuana. Today, no one can doubt that it is, as DEA Administrative Judge Francis L. Young put it, “…among the safest therapeutic substances known to man.” If it were now in the official pharmacopoeia, it would be a serious contender for the title of least toxic substance in that compendium. In its long history, cannabis has never caused a single overdose death.

Then there is the question of who will provide the cannabis. The federal government now provides marijuana from its farm in Mississippi to the seven surviving patients covered by the now-discontinued Compassionate IND program. But surely the government could not or would not produce marijuana for many thousands of patients receiving prescriptions, any more than it does for other prescription drugs.

If production is contracted out, will the farmers have to enclose their fields with security fences and protect them with security guards? How would the marijuana be distributed? If through pharmacies, how would they provide secure facilities capable of keeping fresh supplies? Would the price of pharmaceutical marijuana have to be controlled —not too high, lest patients be tempted to buy it on the street or grow their own; not too low, lest people with marginal or fictitious “medical” conditions besiege their doctors for prescriptions?

What about the parallel problems with potency? When urine tests are demanded of workers, what would be the bureaucratic and other costs of identifying those who use marijuana legally as a medicine as distinguished from those who use it for other purposes?

To realize the full potential of cannabis as a medicine in the setting of the present prohibition system, we would have to address all these problems and more. A delivery system that successfully navigated this minefield would be cumbersome, inefficient, and bureaucratically top-heavy. Government and medical licensing boards would insist on tight restrictions, challenging physicians as though cannabis were a dangerous drug every time it was used for any new patient or purpose. There would be constant conflict with one of two outcomes: patients would not get all the benefits they should, or they would get the benefits by abandoning the legal system for the black market or their own gardens and closets.

The Pharmaceuticalization of Cannabis

A solution now being proposed, notably in the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report, is what might be called the “pharmaceuticalization” of cannabis: prescription of isolated individual cannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids, and cannabinoid analogs. The IOM Report states that “…if there is any future for marijuana as a medicine, it lies in its isolated components, the cannabinoids, and their synthetic derivatives.”

It goes on: “Therefore, the purpose of clinical trials of smoked marijuana would not be to develop marijuana as a licensed drug, but such trials could be a first step towards the development of rapid-onset, non-smoked cannabinoid delivery systems.”

Some cannabinoids and analogs may indeed have advantages over whole smoked or ingested marijuana in limited circumstances. For example, cannabidiol may be more effective as an anti-anxiety medicine and an anticonvulsant when it is not taken along with THC, which sometimes generates anxiety.

Other cannabinoids and analogs may prove more useful than marijuana in some circumstances because they can be administered intravenously. For example, 15 to 20 percent of patients lose consciousness after suffering a thrombotic or embolic stroke, and some people who suffer brain syndrome after a severe blow to the head become unconscious. The new analog dexanabinol (HU-211) has been shown to protect brain cells from damage when given immediately after the stroke or trauma; in these circumstances, it will be possible to give it intravenously to an unconscious person.

Presumably other analogs may offer related advantages. Some of these commercial products may also lack the psychoactive effects which make marijuana useful to some for non-medical purposes. Therefore, they will not be defined as “abusable” drugs subject to the constraints of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act. Nasal sprays, vaporizers, nebulizers, skin patches, pills, and suppositories can be used to avoid exposure of the lungs to the particulate matter in marijuana smoke.

The question is whether these developments will make marijuana, the plant, medically obsolete. Surely many of these new products would be useful and safe enough for commercial development. It is uncertain, however, whether pharmaceutical companies will find them worth the enormous development costs.

Some may be (for example, a cannabinoid inverse agonist that reduces appetite might be highly lucrative), but for most specific symptoms, analogs or combinations of analogs are unlikely to be more useful than natural cannabis. Nor are they likely to have a significantly wider spectrum of therapeutic uses, since the natural product contains the compounds (and synergistic combinations of compounds) from which they are derived. For example, the naturally occurring THC and cannabidiol of marijuana, as well as dexanabinol, protect brain cells after a stroke or traumatic injury.

The cannabinoids in whole marijuana can be separated from the burnt plant products (which comprise the smoke) by vaporization devices that will be inexpensive when manufactured in large numbers. These devices take advantage of the fact that finely chopped marijuana releases the cannabinoids by vaporization when air flowing through the marijuana is held within a fairly large temperature window below the ignition temperature of the plant material.

Inhalation is a highly effective means of delivery, and faster means will not be available for analogs (except in a few situations such as parenteral injection in a patient who is unconscious or suffering from pulmonary impairment).

It is the rapidity of the response to inhaled marijuana which makes it possible for patients to titrate the dose so precisely. Furthermore, any new analog will have to have an acceptable therapeutic ratio. The therapeutic ratio (an index of the drug’s safety) of marijuana is not known because it has never caused an overdose death, but it is estimated, on the basis of extrapolation from animal data, to be an almost unheard of 20,000 to 40,000.

The therapeutic ratio of a new analog is unlikely to be higher than that; in fact, new analogs may be much less safe than smoked marijuana because it will be physically possible to ingest more of them. And there is the problem of classification under the Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act for analogs with psychoactive effects. The more restrictive the classification of a drug, the less likely drug companies are to develop it and physicians to prescribe it.

Recognizing this economic fact of life, Unimed Pharmaceuticals Inc. has fairly recently succeeding in getting Marinol (dronabinol) reclassified from Schedule 2 to Schedule 3. Nevertheless, many physicians will continue to avoid prescribing it for fear of the drug enforcement authorities.

G.W. Pharmaceuticals

A somewhat different approach to the pharmaceuticalization of cannabis is being taken by a British company, G. W. Pharmaceuticals. It is attempting to develop products and delivery systems which will skirt the two primary popular concerns about the use of marijuana as a medicine: the smoke and the psychoactive effects (the “high”).

To avoid the need for smoking, G. W. Pharmaceuticals has developed an electronically controlled dispenser to deliver cannabis extracts sublingually in carefully controlled doses. The company expects its products (extracts of marijuana) to be effective therapeutically at doses too low to produce the psychoactive effects sought by recreational and other users. My clinical experience leads me to question whether this is possible in most or even many cases. Furthermore, the issue is complicated by tolerance to the psychoactive effects. Recreational users soon discover that the more often they use marijuana, the less “high” they experience. A patient who smokes cannabis frequently for the relief of, say, chronic pain or elevated intraocular pressure will experience little or no “high.”

As a clinician who has considerable experience with medical cannabis use, I have to question whether the psychoactive effect is always separable from the therapeutic. And I strongly question whether the psychoactive effects are necessarily undesirable. Many patients suffering from serious chronic illnesses report that cannabis generally improves their spirits. If they note psychoactive effects at all, they speak of a slight mood elevation — certainly nothing unwanted or incapacitating.

In principle, sublingual administration of cannabis extracts via such a dispenser has the same advantages as smoked marijuana — rapid onset and, therefore, easy self-titratability of the desired therapeutic effect. But the design of the G. W. Pharmaceutical dispenser negates this advantage.

The device has electronic controls that monitor the dose and prevenlt delivery if the patient tries to take more than the physician or pharmacist has set it to deliver. The proposal to use this cumbersome and expensive device apparently reflects a concern that patients cannot accurately titrate the therapeutic amount or a fear that they might take more than they need and experience some degree of “high” (always assuming, doubtfully, that the two can easily be separated, especially when cannabis is used infrequently).

Because these products will be considerably more expensive than natural marijuana, they will succeed only if patients and physicians consider the health risks of smoking marijuana (with and without a vaporizer) much more compelling than is justified by either the medical or epidemiological literature and they believe that it is essential to avoid any hint of a psychoactive effect.

In the end, the commercial success of any psychoactive cannabinoid product will depend on how vigorously the prohibition against marijuana is enforced. It is safe to predict that new analogs and extracts will cost much more than whole smoked or ingested marijuana even at the inflated prices imposed by the prohibition tariff. I doubt that pharmaceutical companies would be interested in developing cannabinoid products if they had to compete with natural marijuana on a level playing field. The most common reason for using Marinol is the illegality of marijuana, and many patients choose to ignore the law for reasons of efficacy and cost.

The number of arrests on marijuana charges has been steadily increasing and has now reached more than 700,000 annually, yet patients continue to use smoked cannabis as a medicine. I wonder whether any level of enforcement would compel enough compliance with the law to embolden drug companies to commit the many millions of dollars it would take to develop new cannabinoid products.

Unimed is able to profit from the exorbitantly priced dronabinol only because the United States government underwrote much of the cost of development. Pharmaceutical companies will undoubtedly develop useful cannabinoid products, some of which may not be subject to the constraints of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act. But, it is unlikely that this pharmaceuti-calization will displace natural marijuana for most medical purposes.

It is also clear that the realities of human need are incompatible with the demand for a legally enforceable distinction between medicine and all other uses of cannabis. Marijuana use simply does not conform to the conceptual boundaries established by twentieth century institutions. It enhances many pleasures and it has many potential medical uses, but even these two categories are not the only relevant ones. The kind of therapy often used to ease everyday discomforts does not fit any such scheme.

In many cases what lay people do in prescribing marijuana for themselves is not very different from what physicians do when they provide prescriptions for psychoactive or other drugs. The only workable way of realizing the full potential of this remarkable substance, including its full medical potential, is to free it from the present dual set of regulations — those that control prescription drugs in general and the special criminal laws that control psychoactive substances.

These mutually reinforcing laws established a set of social categories that strangle its uniquely multifaceted potential. The only way out is to cut the knot by giving marijuana the same status as alcohol — legalizing it for adults for all uses and removing it entirely from the medical and criminal control systems.

Two powerful forces are now colliding: the growing acceptance of medical cannabis and the proscription against any use of the plant marijuana, medical or non-medical. There are no signs that we are moving away from absolute prohibition to a regulatory system that would allow responsible use of marijuana. As a result, we are going to have two distribution systems for medical cannabis: the conventional model of pharmacy-filled prescriptions for FDA-approved cannabinoid medicines, and a model closer to the distribution of alternative and herbal medicines.

The only difference, an enormous one, will be the continued illegality of whole smoked or ingested cannabis. In any case, increasing medical use by either distribution pathway will inevitably make growing numbers of people familiar with cannabis and its derivatives. As they learn that its harmfulness has been greatly exaggerated and its usefulness underestimated, the pressure will increase for drastic change in the way we as a society deal with this drug.