September 21, 2018 Earlier this month the US Drug Enforcement Administration authorized UC San Diego’s Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research (CMCR) to import cannabis from a Canadian corporation, Tilray, to test its effectiveness in reducing “Essential Tremor,” a condition affecting 10 million US Americans. (As reported here.)

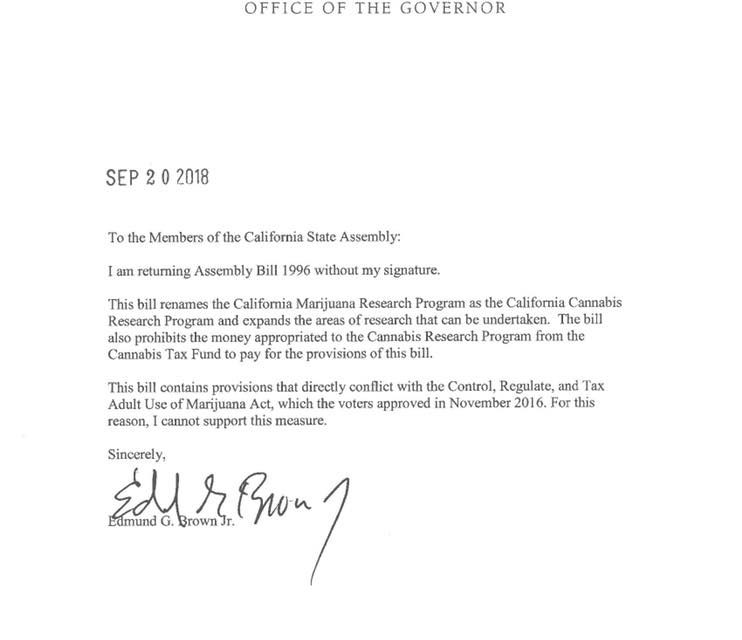

Last week Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed a bill allocating $2 million to the CMCR. Brown’s statement said the bill would violate California’s Adult Use of Marijuana Act, passed by the voters in 2016. Asked which provisions of AUMA were supposedly violated, Dale Gieringer of California NORML forwarded this explanation from the office of Assemblyman Tom Lackey (Republican of Antelope Valley-Santa Clarita, who introduced the vetoed bill):

(e) The Controller shall next disburse the sum of two million dollars ($2, 000, 000) annually to the University of California San Diego Centerfor Medicinal Cannabis Research to further the objectives of the Center including the enhanced understanding of the efficacy and adverse effects of marijuana as a pharmacological agent.

(2) The program shall develop and conduct studies intended to ascertain the general medical safety and efficacy of cannabis and, if found valuable, shall develop medical guidelines for the appropriate administration and use of cannabis. The studies may examine the effect of cannabis on motor skills, the health and safety effects of cannabis, and other behavioral and health outcomes.

Recently Jerry Brown appointed Juan Pedro Gaffney, an old school chum, to the Workers Compensation Board, a $153,000/year job. Willie Brown noted in his SF Chronicle column that Jerry was finally coming out as a pol who does favors for his friends.

Jerry Brown’s well-publicized favor to Gaffney was a misdirection play that deflected attention from the $15 billion gift the governor lavished on his friends at PG&E by signing legislation —which his staff helped push through— that will make California taxpayers financially responsible for the 2017 Wine Country fires, every one of which was caused by fallen PG&E power lines or sparking transformers. PG&E’s responsibility for starting each of the 11 fires was documented by phone calls to fire departments. There was no ambiguity as to cause.

While the legislators were being lobbied to let PG&E off the hook, a media campaign bombarded the public. Earnest ads emphasized the reality of hotter summers and greater fire danger in the years ahead, which we, the people, have to expect and budget for. No mention was made of exonerating PG&E financially for 2017. The ads were all about the future.

Another arm of the campaign featured a computerized war room from which highly alert PG&E operatives will from now on scan the forests of California while monitoring all the emergency phone lines.

The obvious way to reduce the fire danger in Northern California — bury the power lines— never gets mentioned. It would be labor-intensive and the workers would have to be paid.

PG&E ads are always politically correct in terms of personnel. The recent non-stop campaign (which ended as soon as Brown signed the bill) emphasized that PG&E interacts closely with police and fire departments and should be honored as First Responders.

PG&E should bury its power lines like the corporate media buried the $15 billion giveaway story in the print edition (left, below) and online.

Collision in My Memory

News of Jerry Brown rewarding his old friend —plus the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research (CMCR) not getting a $2 million allocation— caused a collision in my memory.

When California passed Prop 215 in November, 1996, I started compiling a chronology of the medical marijuana movement. I was then managing editor of Synapse, the internal weekly at UCSF, staffed mainly by medical students, and I was in close contact with Tod Mikuriya, MD, the world’s leading authority on cannabis as medicine, and Dennis Peron, who was fighting in court to reopen the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club. Their input helped inform the chronology.

Here’s the entry for February 6, 1997:

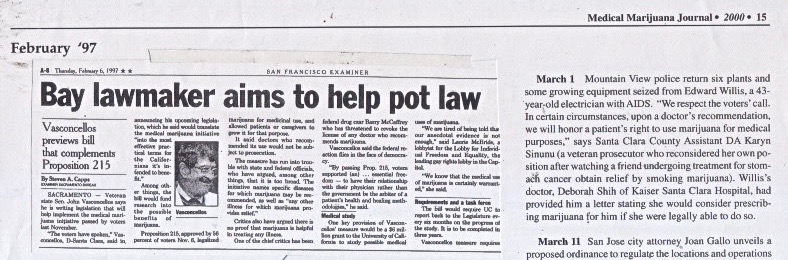

“Bay Lawmaker Aims to Help Pot Law” —SF Examiner headline. State Sen. John Vasconcellos announces that he will introduce legislation to “help implement” Prop 215. Americans for Medical Rights claims credit for helping to draft the aptly named “enabling legislation.” Dennis Peron is suspicious. “Prop 215 doesn’t need any help.”

Marijuana reform advocates considered Vasconcellos a major ally, but Dennis’s suspicions would turn out to be well-founded. “One key provision of Vaconcellos’ measure,” the Examiner story stated, “would be a $6 million grant to the University of California to study possible medical uses of marijuana.” Eventually Vasconcellos did get the legislature to grant $8.6 million (paid out over three years) to create the Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research at UC San Diego. It would be co-directed by Igor Grant, MD, and Drew Mattison, a clinical psychologist.

Tod Mikuriya deplored the research agenda set by the CMCR. He pointed out that California voters intended Prop 215 as a rebuke to the federal government. We revised state law in defiance of the federal prohibition and despite the warnings of the medical establishment. Vasco’s CMCR restored compliance, going hat in hand to the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Drug Enforcement Administration to request cannabis grown at the University of Mississippi. Tod thought the CMCR —created in response to Prop 215— should study the effects of the cannabis being grown and used legally by Californians. The CMCR applied to NIDA and after a year of bureaucratic stalling and DEA inspections of each researcher’s lab to make sure that the Devil Weed would be locked in a safe that was properly embedded in cement, a product from Ol’ Miss would be shipped. In the years ahead, six studies would be conducted under CMCR auspices and all would confirm that cannabis provides medical benefit. .

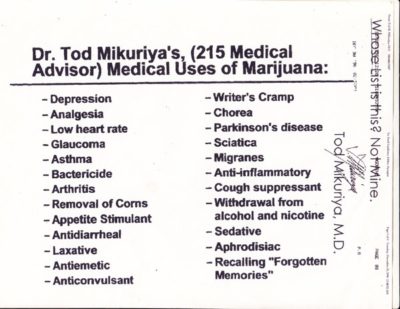

When Prop 215 passed, Mikuriya was known as the only MD in California who would readily approve cannabis use for less-than-grave conditions.  The Clinton Administration response to Prop 215 —announced at a December 30, 1996 press conference starring Drug Czar McCaffrey, Attorney General Reno, Health & Human Services Director Shalala, and Alan Leshner of NIDA— was to threaten to pull the licenses of any cannabis-approving doctors. On display was a chart entitled “Dr. Tod Mikuriya’s (215 Medical Advisor) Medical Uses of Marijuana.” The list had been culled from the internet by an Army officer named DesRoches, one of many aides brought over from the Pentagon by McCaffrey. The federal officials

The Clinton Administration response to Prop 215 —announced at a December 30, 1996 press conference starring Drug Czar McCaffrey, Attorney General Reno, Health & Human Services Director Shalala, and Alan Leshner of NIDA— was to threaten to pull the licenses of any cannabis-approving doctors. On display was a chart entitled “Dr. Tod Mikuriya’s (215 Medical Advisor) Medical Uses of Marijuana.” The list had been culled from the internet by an Army officer named DesRoches, one of many aides brought over from the Pentagon by McCaffrey. The federal officials

The Soros-funded “professionals” who had taken control of the Prop 215 campaign immediately sought an injunction to prevent the Drug Czar from punishing California doctors who authorized patients to use cannabis. This very good deed was orchestrated by Ethan Nadelmann, director of the group now known as the Drug Policy Alliance. It was also a very bad deed because Tod Mikuriya was excluded form the long list of co-plaintiffs.

John Vasconcellos had been in on the decision to exclude Mikuriya from co-plaintiff status. Nadelmann regarded Tod as “a loose cannon who couldn’t be trusted to stay on message,” according to Randy Nathan, a confidante of Vasco’s. Marcus Conant, a UCSF professor who had treated Kaposi’s Sarcoma patients, was an excellent good choice for lead plaintiff. But there were some 20 co-plaintiffs, and not including Mikuriya was blacklisting plain and simple, a consolidation of power by Nadelmann’s faction. Randy Nathan recalls Vasco chuckling over the choice of Conant: “We knew he’d stay on message because he was trained by the Jesuits.”

If Tod Mikuriya had been one of the co-plaintiffs on Conant v. McCaffrey, the Medical Board of California might have thought twice about prosecuting him. His outspokenness would not have kept federal judge Fern Smith (a Reagan appointee) from ruling in favor of Conant on First Amendment grounds. Nor would Tod’s name on the list of co-plaintiffs have led to a different Constitutional interpretation from Judge William Alsup, who made Smith’s temporary junction permanent, forbidding the feds to punish California doctors who discuss cannabis as a treatment option with their patients.

Excluding Tod Mikuriya from the Conant suit was blacklisting. There’s no other word for it. Removing him and Dennis from the leadership of the medical marijuana movement were necessary first steps on the road to Legalibition.