In 2021 an oddly named drug company headquartered in Ireland, Jazz, acquired GW Pharmaceuticals, a British company whose main asset was Epidiolex a cannabis-based medication that in November, 2013 had been designated an “orphan-drug” by the US Food & Drug Administration to treat a rare form of epilepsy, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epidiolex was soon approved to treat other rare types of epilepsy, Dravet syndrome and tuberous sclerosis complex.

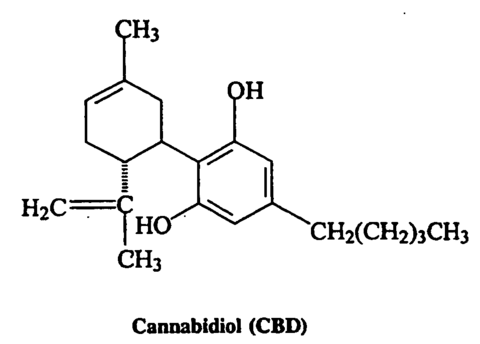

Epidiolex is a “botanical isolate” –meaning it’s simply cannbidiol (CBD) extracted from cannabis plants. The orphan-drug designation somehow made Epidiolex GW’s “intellectual property,” protectable by patent. That protection is why Jazz eventually paid $7.1 billion to make GW a subsidiary.

Last week Jazz filed suit against Teva and 12 other manufacturers of CBD-based anti-seizure meds in the US District Court of New Jersey, claiming infringement on their Epidiolex patent. The defendants have names like Apotex, Padagis, Invagen, Cipla, API Pharma, Lupin Laboratories, Alkem, Taro, Ascent, MSN, Zenara and Biophore. They have all sought FDA “approval to commercially market generic versions of GW’s cannabidiol oral solution drug product prior to the expiration of one or more US Patents.” A long list of relevant patent numbers follows, and the complaint goes on for 322 pages.

Your correspondent doesn’t understand exactly how orphan drug status leads to longterm patent protection, or what the implications are for small-time manufacturers of CBD isolates. More research is needed, to coin a phrase. According to the FDA website;”The FDA has authority to grant orphan drug designation to a drug or biological product to prevent, diagnose or treat a rare disease or condition. Orphan drug designation qualifies sponsors for incentives including:

- Tax credits for qualified clinical trials

- Exemption from user fees

- Potential seven years of market exclusivity after approval.”

Dr. Geoffrey Guy, the co-founder of GW in 1998 with Dr. Brian Whittle, describes himself as “a pharmaceutical entrepreneur” and never pretended he wasn’t out to make money. Guy and Whittle had formed a company called PhytoPharm in 1990. They imported saw palmetto from China to make an effective treatment for prostate problems. It was a financial success. Their brave attempt to make a legal medicine from the strictly prohibited Cannabis plant was inspired by Multiple Sclerosis patients meeting in London who in turn had been inspired by California voters legalizing marijuana for medical use in ’96.

Guy understood that the prevailing wisdom was wrong –THC was not “the active ingredient in Cannabis.” Dr. John McPartland had been emphasizing the role of CBD since 1993, when he presented a poster at the International Cannabinoid Research Society meeting. CBD had always been a major component of the hashish used in India and the Middle East, and that it provided medical benefits equal to THC’s without intoxicating effects, Guy explained to the British regulatory authorities. In a 50-50 formulation, he convinced them, CBD would negate the high. And he promised to deliver his cannabis-based products by a method other than smoking. The Home Office granted approval in early 1998.

GW promptly obtained plants from HortaPharm, a Dutch company run by US expats David Watson and Robert Connell Clarke. Watson and Clarke were devoted pot partisans, 30-somethings from California who had roamed the world searching for “land race strains” of Cannabis that might have unique properties. They moved to Amsterdam in the Just-Say-No 1980s after the FDA granted approval for Marinol, a synthetic THC. “We realized then that the US government was never going to let us do the kind of research with plants that we knew was necessary,” Watson recalls. GW Pharmaceuticals purchased plants for their “genetic library” from Hortapharm. They leased a former military facility with a huge greenhouse in Kent, and began to breed up CBD levels.

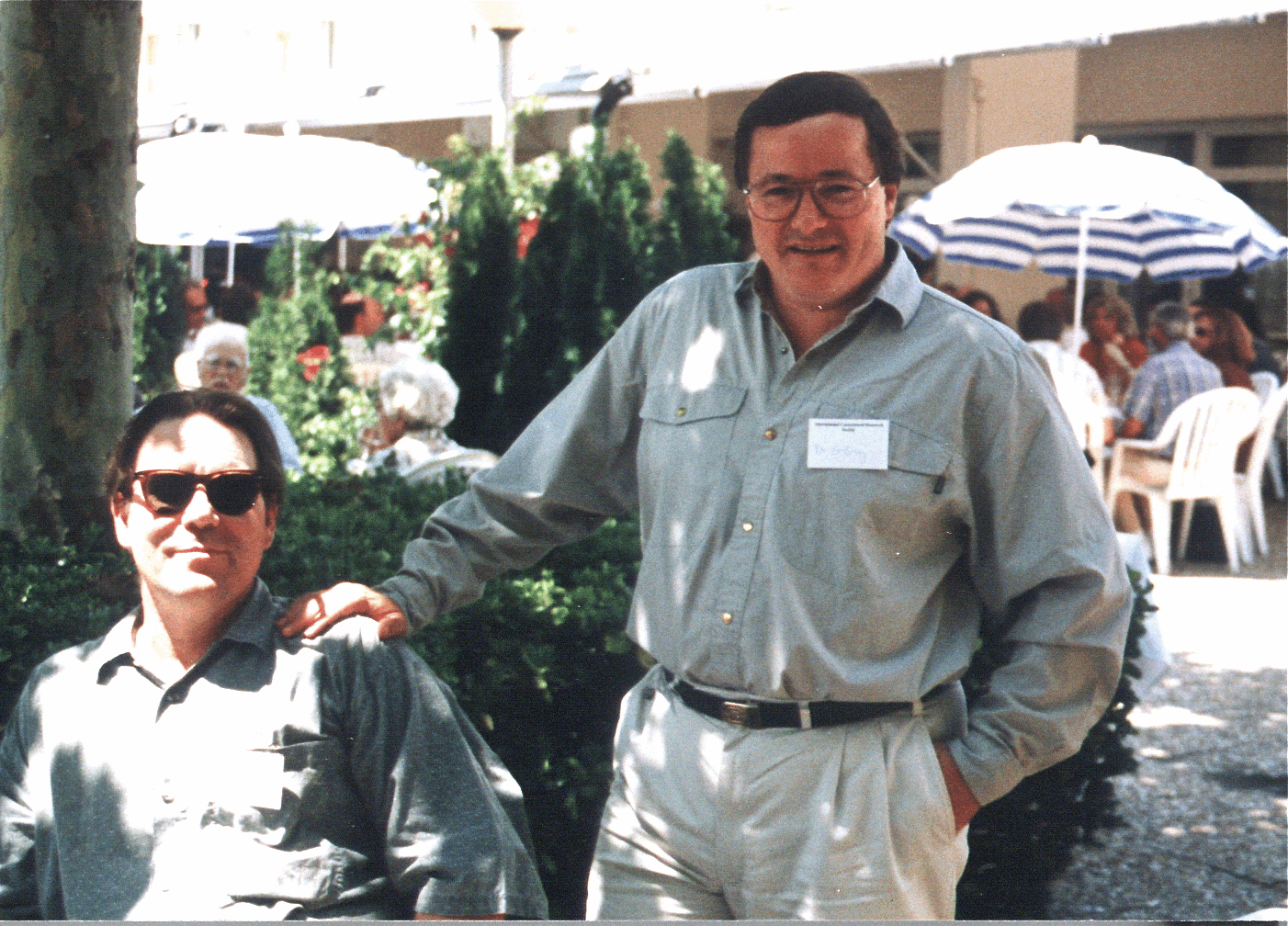

GW sent a large contingent to the 1998 ICRS meeting in Languedoc, France. I was working at UCSF at the time, and used my vacation time to attend and cover it. The photo below is of Dave Watson and Geoffrey Guy. Alexander Cockburn said it reminded him of a classified ad his father had seen in a London newspaper at the height of the depression: “Man with knife and fork wishes to meet man with steak and kidney pie.”

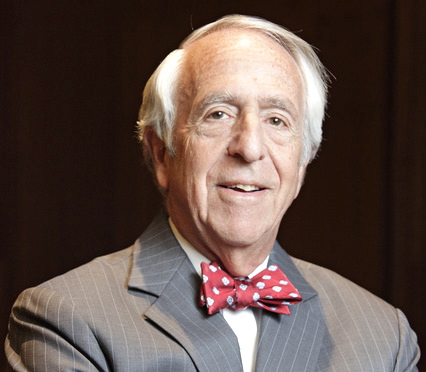

In the years that followed, researchers funded by GW began publishing papers showing that CBD was safe and effective medicine in animal studies. O’Shaughnessy’s publicized their findings and the credibility of California activists was enhanced. But early on, Lester Grinspoon, a PC psychiatrist (as in Pro-Cannabis and left-leaning) saw that GW was taking the first steps toward making cannabis safe for capital. In a piece called “The Marijuana Problem” in the Summer 2003 issue of O’S, Grinspoon wrote, “A solution now being proposed, notably in the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report, is what might be called the ‘pharmaceuticalization’ of cannabis: prescription of isolated individual cannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids, and cannabinoid analogs. The IOM Report states that ‘If there is any future for marijuana as a medicine, it lies in its isolated components, the cannabinoids, and their synthetic derivatives.’

“It goes on: ‘Therefore, the purpose of clinical trials of smoked marijuana would not be to develop marijuana as a licensed drug, but such trials could be a first step towards the development of rapid-onset, non-smoked cannabinoid delivery systems.'”

Grinspoon was renarkably prescient. He noted, “Some cannabinoids and analogs may indeed have advantages over whole smoked or ingested marijuana in limited circumstances. For example, cannabidiol may be more effective as an anti-anxiety medicine and an anticonvulsant when it is not taken along with THC, which sometimes generates anxiety.”

For years I would debrief Guy on the last day of ICRS meetings and report his observations and plans. After Grinspoon’s piece appeared in our journal (Dr. Tod Mikuriya, the prime mover, was co-editor), Guy mentioned that it had hurt his feelings “a bit.” I wrote a song intended to cheer him up. (Sativex was GW’s flagship product, which now has been approved in 29 countries to treat spasticity.)

The Ballad of Grinspoon and Guy

Sativa is a pretty plant and it grows tall and green

with 66 canny cannabinoids and the spicy sweet terpenes

Guy says I can market this I’ll just put it in a spray

Grinspoon says It grows in the ground why should people have to pay too much?

Guy says some prefer it neat and some don’t like the high

Grinspoon says the government won’t even let ’em try

Euphoria’s a side effect that could do some people good

Guy says I’m all for you, Les, please don’t let me be misunderstood

We’re dealing with a SYSTEM that is not about to change

Grinspoon says Well why not reinvent the grange?

And let a thousand farmers grow all them helpful strains

Guy says my approval hasn’t been easy or cheap to almost obtain

Sativex is a useful drug and it bears the Bayer cross

Grinspoon shakes the bottle with a subtle sense of loss

“You’re right from your side and I am right from mine

We’re just one too many markets and the wide, green Atlantic behind.”

GW’s action against the generics makers was reported on a few legal websites and by Kyle Jaeger on marijuanamoment.com (a consistently reliable source of info). But otherwise coverage has been non-existent. Let the record state that GW Pharmaceuticals played an indispensable role in creating the medical marijuana movement and the legal cannabis industry that the movement gave rise to. Only a Commie would question Jazz Pharmaceuticals’ right to now cash in to the max.