The New York Times, awake at last to the significance of Cannabis, has begun reporting recent developments. (The editorial-page editors awoke about two years ago.) The week of Thanksgiving the Times ran four pieces rife with news and analysis that California activists might not have gotten from their usual online sources.

November 22, on page 13 of the front section, in a piece hedded “Medical Marijuana Is Legal in California. Sometimes,” Thomas Fuller recounted the takedown and rebound of CannaCraft. O’Shaughnessy’s has a piece in the works on this very subject! We’ll have to find an angle, because Fuller tells it straight:

SANTA ROSA, Calif. — California’s multibillion-dollar marijuana industry, by far the nation’s largest, is crawling out from the underbrush after voters opted to legalize cannabis in this month’s election. In Sonoma County alone, an estimated 9,000 marijuana cultivation businesses are operating in a provisional gray market, with few specific regulations, and are now looking to follow the path of the wine industry, which emerged from its own prohibition eight decades ago and rose to the global prominence it enjoys today.

But the bruising ordeals of one of the state’s largest cannabis companies, CannaCraft, have made many in the marijuana industry fearful, and they suggest a long and bumpy road from marijuana’s approval at the ballot box to the same on-the-ground acceptance enjoyed by wine and beer businesses.

CannaCraft produces medical marijuana products, which have been legal in the state for two decades, but operated in a kind of Wild West, unregulated market. In June, the company’s newly opened headquarters was raided by federal and local law enforcement officers, who said the process it used to make marijuana products was dangerous and illegal. The agents seized $5 million in equipment, inventory and cash. This year, company drivers have twice been stopped by the California Highway Patrol, and, in one case, 1,600 pounds of marijuana was seized.

The business’s troubles may be a sign of things to come after the drug’s broader legalization, as medical cannabis companies like CannaCraft continue to be whipsawed by the lack of clear state regulations and the glaring contradiction between a federal ban on marijuana and still-evolving state laws that should, in theory, shelter the companies from prosecution. Cannabis enterprises deal almost exclusively in cash because banks, fearing federal consequences, will not take their business.

“They are asking people to come out into the open, but there’s this mistrust,” said Dennis Hunter, 43, a founder of CannaCraft who has spent his entire adult life as a marijuana farmer. Mr. Hunter has been arrested three times, and he was sentenced in 2005 to six and a half years in federal prison for growing marijuana and fleeing during a raid.

“You are basically hiding for 20 years, and then you swing the doors wide open. It’s a risk,” he said. “And there’s no clear path.”

The national election threatens an informal, fragile truce between states that have legalized the drug and the federal government. President-elect Donald J. Trump’s proposed choice of Senator Jeff Sessions of Alabama to serve as attorney general has roiled the cannabis industry because of comments the Republican senator has made about the drug. At a Senate hearing in April, Mr. Sessions described marijuana as a “very real danger.”

“We need grown-ups in charge in Washington to say marijuana is not the kind of thing that ought to be legalized,” Mr. Sessions said at the hearing. Cannabis advocates believe that, during a Trump presidency, the Drug Enforcement Administration would reinforce its hard-line stance on marijuana. In August, the federal agency reaffirmed the status of marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug, the most dangerous class of drugs, which also includes heroin.

Thousands of cannabis companies in California are now weighing whether they should register with local governments, pay local taxes and be regulated like all other businesses, or continue to operate in the gray market.

The plight of CannaCraft, which despite the June raid has had sales of $10 million so far this year, has been closely watched by other companies in the marijuana business here because of the way the company began openly courting state and local lawmakers and applying for licenses like any other business.

This year, the company moved into offices in a corporate park in Santa Rosa that were once occupied by a company that manufactured heart stents, and it obtained a business tax license as a cannabis company and permission to operate agricultural processing machinery.

“Their zoning was good. The choice of building location was good,” said Julie Combs, a member of the Santa Rosa City Council. “They were certainly using an open-door policy.”

In May, the company hosted nearly 50 lawmakers and regulators from Sacramento, the state capital, to demonstrate the process it uses to produce the soft-gel capsules and other cannabis-based products that do not involve smoking. As technicians in white lab coats operated machines designed to detect impurities in their products, Mr. Hunter demonstrated to lawmakers the extractors that produce oils from the plant.

“Because cannabis has a stigma around it, we really needed to come out and change people’s image of what a cannabis company looked like,” Mr. Hunter said during a recent interview at the company’s headquarters. “We knew we were going to be one of the first through the gate, so we wanted to set a good example for the industry that looked professional and was clean.”

But two weeks after the visit by lawmakers, around 100 officers and agents wearing tactical gear, and representing multiple law enforcement agencies, raided the company’s headquarters and four other facilities. The officers broke down doors and, according to the company, seized around $500,000 in cash, 22 machines worth $3 million and $1.5 million worth of cannabis products.

Mr. Hunter was arrested and held on $5 million bail, which critics of the raid said was an unusually large amount.

Lt. Michael Lazzarini of the Santa Rosa Police Department’s investigations bureau said the police had acted on the basis of a “public safety risk” caused by the cannabis manufacturing process, which he described as “illegal and volatile.”

“There’s this huge desire to make Santa Rosa a place for this industry to thrive,” Lieutenant Lazzarini said. “But then a lot of these businesses operate outside of the scope of local, state or federal regulations.”

The raid prompted lawmakers in Sacramento to enact regulations in September to clarify that the extraction procedure was legal. Lieutenant Lazzarini said that he was aware of the change in the law, but that his department’s investigation was continuing.

Mr. Hunter was released two days after the raid, and the bail requirement was dropped when the district attorney decided not to press charges against him, according to Lieutenant Lazzarini. But the company’s equipment and cash have not been returned.

The raid has been criticized by some local officials who said it sent the wrong message to other companies that were seeking to shed their clandestine past. Ms. Combs, the Santa Rosa City Council member, described the raid as an overreaction to what amounted to suspicion of a permit violation.

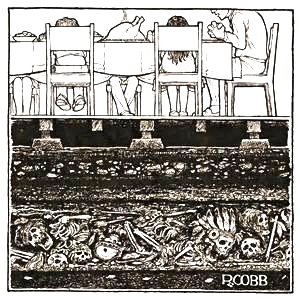

“If there is an issue with a manufacturing process being unsafe, we don’t normally break down doors and take the payroll,” she said. “It’s almost as if law enforcement, at multiple levels, are like the Japanese soldiers on an island still fighting a war that is over.”

Bob Aaronson, the independent auditor of the Santa Rosa Police Department, described the raid as “something I’m not happy with.”

“The guy was trying to comply to the extent he can,” Mr. Aaronson said, referring to Mr. Hunter.

Russ Baer, a spokesman for the Drug Enforcement Administration, confirmed that agents had taken part in the raid, but would not comment on the specific reasons for their involvement.

The agency’s position is that marijuana has “never been determined to be medicine,” he said.

Rob Bonta, a California state assemblyman, said the clash between federal and state laws added only one level of confusion. It was nearly two decades after medical marijuana became legal in California that state legislators in 2015 passed regulations on licensing, taxation and pesticide standards. And although that law, the Medical Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act, is scheduled to take effect in 2018, there are now questions as to how much the medical law will overlap with recreational marijuana regulations, which have yet to be drawn up.

“There’s an ongoing challenge with clarity,” Mr. Bonta said. “There’s not enough certainty that has trickled down to the street level, where law enforcement has clear direction.”

Preparations for full legalization have revealed the massive scale of the industry, said Terry Garrett, a manager of Sustaining Technologies, a marketing company.

He calculates annual sales of raw marijuana plants in Sonoma County alone at around $3 billion, six times more than the total sales of wine grapes.

“I empathize with all the players, the regulators and the regulated,” Mr. Garrett said. “I didn’t realize the scale of the problem until I realized how big the industry is.”

Thomas Fuller filed another thorough story a few days later exposing the poverty in which the field hands live in Salinas.