Dr. Carl Hart, a neuroscientist at Columbia University, is the bravest, most audacious, most radical thinker in the drug-policy-reform field. His latest book was assessed in the New York Times Book Review 1/17/21 by a woman named Casey Schwartz. Her tag included an acrobatic sentence that might mollify the influential reformers criticized by Hart. I commented on it in a letter the Times is unlikely to run:

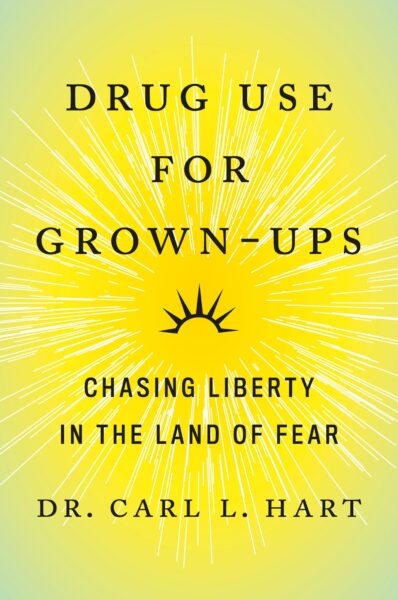

In “Drug Use for Grown-Ups,” I learn from Casey Schwartz’s review, Carl Hart asks: what’s wrong with being a regular heroin user?

Her review is favorable, except for: “Hart’s writing can turn from passionate and moral to what feels like score-settling, undercutting the tenor of his narrative.”

I ask: what’s wrong with score-settling?

Fred Gardner, Alameda, CA

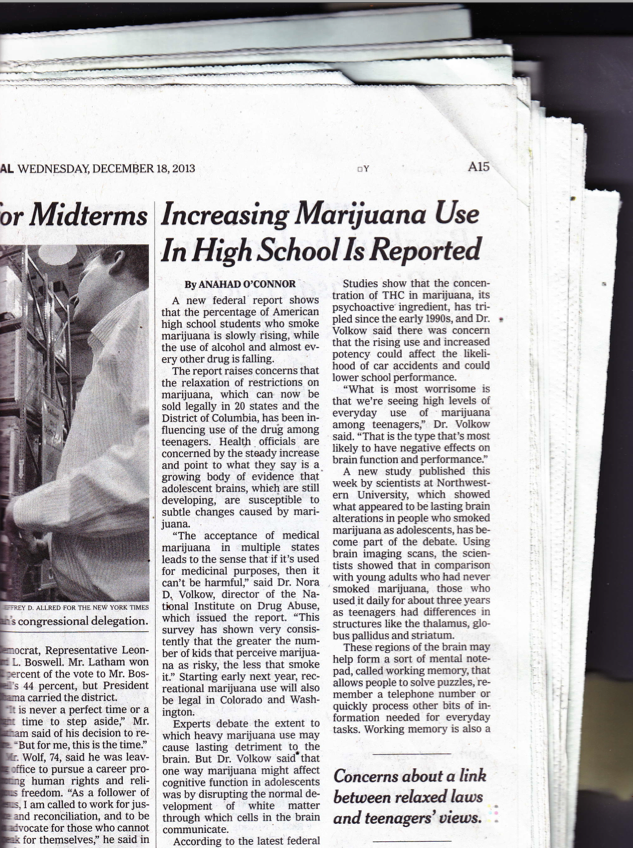

Gone are the days when a hack writer like me could request and get review copies from book publishers. I paid online for “Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear” and eagerly await delivery of Hart’s reasoning and revelations. According to Schwartz’s review, “Hart argues the drug war has in fact succeeded, not because it has reduced illegal drug use in the United States (it hasn’t), but because it has boosted prison and policing budgets, its true, if unstated, purpose.”

Gone are the days when a hack writer like me could request and get review copies from book publishers. I paid online for “Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear” and eagerly await delivery of Hart’s reasoning and revelations. According to Schwartz’s review, “Hart argues the drug war has in fact succeeded, not because it has reduced illegal drug use in the United States (it hasn’t), but because it has boosted prison and policing budgets, its true, if unstated, purpose.”

About 10 years ago Ethan Nadelmann, PhD, Executive Director of the Drug Policy Alliance, instructed his followers to always refer to the War on Drugs as a failure. The DPA honcho, though supposedly a liberal fellow, was very strict about everyone “staying on message.” Because almost all activists and politicians craved some of the funding Nadelmann doled out on behalf of George Soros (about $6 million annually), their speeches and blog posts made a mantra of “the failed war on drugs.” O’Shaughnessy’s ran a retrograde message, to no effect.

The War on Drugs is a Success!

Ostensible allies advised that it was my own fault if I got scorned by the grant givers. I sensed them thinking I deserved it. “You’re not a team player,” explained Ed Rosenthal in an angry Bronx voice. It was never true. If Carl Hart has a team, I want to be on it.

Hart’s line on heroin jibes exactly with what I was told by Vernon Grigg, the head of Narcotics prosecutions for the district attorney of San Francisco, when I became Terence Hallinan’s press secretary in 2000. Vernon’s office was not far down the hall (which ran the length of a city block) from mine, and I often popped in to ask rudimentary questions. He was very droll and a willing teacher, though his workload was enormous. One morning I found him glaring at the overlapping piles of documents and forms that completely covered an old oak desk. “My personal goal for today,” said Vernon, is ‘See the wood.'”

When I first visited the jail, which was on the fifth floor, Vernon made a theatrical welcoming gesture as the elevator doors opened. “…And this is where we keep our Negroes,” he said. Sure enough, as I stepped out, every single prisoner in view was as brown-skinned as Vernon.

After the actor Philip Seymour Hoffman died of a heroin overdose in February 2014, the friend who had sold him his fatal supply —a musician named Robert Aaron— was arrested by publicity-seeking New York City cops. Aaron was charged with possessing heroin and intent to sell. He did time in jail and at a residential treatment facility. His story was recounted sympathetically in the New York Times Magazine by John Leland. Some excerpts follow:

Though he knew the stories of renowned musicians like Charlie Parker or Chet Baker who used heroin, he said he was never drawn to it for the romance. “It’s more like the thing itself,” he said. “Honestly, I don’t think anybody I know romanticized it as much as they liked it. It’s got good qualities.”

He hesitated, not wanting to be a promoter for dope, he said.

“A lot of times you have a deadline and you have to work for 24 hours. This lets you do it with no pain, no tiredness,” he went on. “If I have to write a book, get me high — I’ll have the book written in two weeks. You’re lucid. And emotions don’t affect you as much — your anger — it bottles up your feelings. It makes you more rational, or you think you are, anyway. You sleep wonderfully. I’m a lifelong insomniac.”

He added, “Everything has its good points and bad points. The bad point is the dependence.”

He restricted his heroin use to snorting, he said, because even among musicians, track marks carried a stigma…

“He was always evolving,” said Eric Andersen, 71, a veteran folk singer who recruited Mr. Aaron to produce and play on several albums. “He is telepathic as a musician. He was completely dedicated and loyal to the job. Absolutely dedicated. He lived for his art. He personifies a cool that transcends the hot temperaments.”

If drugs were a part of his evolution, they were not the center. For concert tours and a three-year residence

in Paris, he said, he stopped using heroin without much difficulty. James Chance brought Mr. Aaron into his punk-funk band James White and the Blacks in 1981 and has worked with him ever since, taking him on tours of Europe and Japan. In all that time, he said, Mr. Aaron’s drug use never interfered with his playing.

“Not at all,” Mr. Chance said. “He’s always been a total professional. Robert’s like the most versatile musician I’ve ever worked with.”

Like other friends interviewed for this article, Mr. Chance spoke protectively of Mr. Aaron, whom he called “a real gentleman.”

“There’s a whole image that people get from the media about people who use narcotics, that they’re completely crazy and unreliable,” Mr. Chance said. “That’s not necessarily true. There’s a lot of people who are totally functional, and you would never know that they used anything. And Robert is one of them.”